How Manchester United crumbled after Sir Alex Ferguson’s exit from the once-mighty club

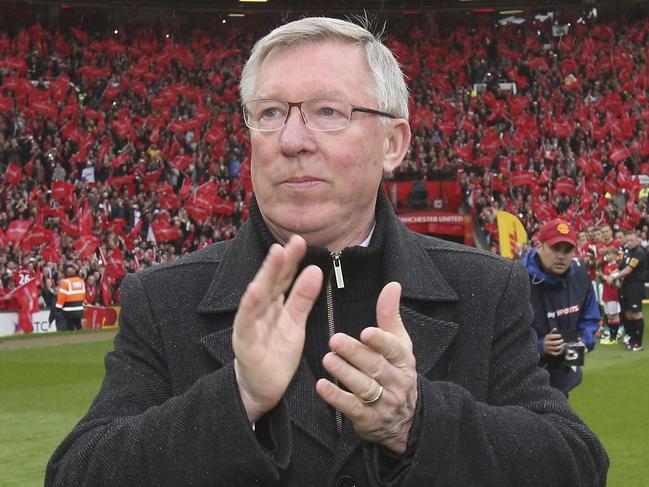

When Sir Alex Ferguson made his retirement speech on the Old Trafford pitch on May 12, 2013, he uttered firm, famous words – yet it has been disaster at Manchester United ever since.

Football

Don't miss out on the headlines from Football. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Sir Alex Ferguson made his retirement speech on the Old Trafford pitch on May 12, 2013, his famous words were: “Your job now is to stand by your new manager.” It was a message to supporters, and the football club he built. The rain fell, the sky darkened and, in a black overcoat, Fergie gripped the mic tight.

Last week Manchester United fans were being asked to stand by their sixth new manager since Ferguson left. Erik ten Hag’s appointment on Monday came at the end of a season in which the club failed to land a title for the ninth year running and finished the Premier League with their lowest top-flight points total since 1990.

For all the sadness at the club about Ferguson’s departure that day nine years ago, there was hope in the knowledge that he had hand-picked his successor. David Moyes was in Manchester with his wife, Pamela, on May 1 when the call came. The pair were visiting a jeweller to get the strap adjusted on the watch that she bought for his 50th birthday when Moyes’s phone went and Ferguson’s name flashed on the screen.

“Can you come over to the house?” said that inimitable voice.

Half an hour later, Moyes was at Ferguson’s home in Wilmslow, being handed a mug of tea and some extraordinary news. “David, I’m retiring, you’re going to be the new manager of Manchester United,” Ferguson said. They went upstairs and discussed the club. Ferguson was handing over a squad that nine days previously had clinched United’s 13th Premier League title in 20 seasons. However, there was recognition that new blood was required, and that areas of the club – the academy, for example – needed to be refreshed.

An hour or so later, Moyes was leaving Wilmslow, the biggest job in football his.

Over the next 48 hours he met the club’s recently appointed executive vice-chairman, Ed Woodward, and members of the Glazer family, the billionaire Americans who owned the club, and quickly agreed a contract. It was for six years – a symbolic span, given that Ferguson required six full seasons to win his first English title after joining United from Aberdeen during the 1986-87 campaign.

For Moyes, there were two immediate priorities. The first was appointing the right staff, and he met Rene Meulensteen, whom he wanted to keep as assistant manager. Second was to do everything possible to secure the two big signings he felt the club needed: Cesc Fabregas, who was unsettled at Barcelona, and Gareth Bale, who was leaving Tottenham Hotspur and hoped to go to Real Madrid, but spent May and June waiting for the Spanish giants to make a move.

Moyes was desperate to get to work immediately but was not able to join United until July 1, and found himself behind the clock from the start. By then Meulensteen had changed his mind after suggesting that he would stay, Madrid were in talks with Bale and no progress had been made on Fabregas. Why did he have to wait? Because his Everton contract did not run out until June 30 and United did not pay the compensation to secure him earlier.

They were basking in record revenues and the thinking behind making Moyes wait would seem extraordinary to nearly anyone in football. Perhaps anyone except those who have worked for Woodward and the Glazers. Bottom line over scoreline – a mindset that Moyes’s successor, Louis van Gaal, believes he experienced too.

“Manchester United is a commercial club … one can do better coaching at a football club,” Van Gaal said in March when asked whether Ten Hag should take the Old Trafford manager’s job.

A sense Moyes soon developed – that those at the top at United did not realise the task their club faced – would be shared by Van Gaal and his staff. Frans Hoek, Van Gaal’s No.2 and goalkeeping coach, told The Sunday Times: “When rebuilding is needed everyone has to stand behind that and speak the same words. That comes down to how much you trust the manager – and it means that the people standing behind it [the hierarchy of the club] need to have the knowledge and understand the process.”

Working with Van Gaal, Hoek had witnessed how other leading clubs organised themselves and supported managers. “Take Bayern [Munich] – the organisational structure is a guarantee that you are always working at the top level,” Hoek said. “In our time, you had guys like [Uli] Hoeness, [Karl-Heinz] Rummenigge [club legends who are now board members], who have a clear vision and philosophy. You can always lean on them – and they’re also very capable of judging what is going on, the work of the manager. That is the most perfect combination in the football world.”

And how did that compare with their United experience? “You could put a question mark about how that structure is at Manchester United.”

The summer of 2013 wound on unsatisfactorily at Old Trafford. After strains in his relationship with Ferguson, Wayne Rooney had entered the final two years of his contract without an extension proposed – and was being wooed by Chelsea. United had two bids rejected for Fabregas, who then announced that he was staying at Barcelona. Bale was also slipping away, with Real now negotiating with Tottenham, and United’s transfer summer took on a farcical edge.

Moyes wanted two players from his former club: Leighton Baines, whose 35 assists in five seasons made him the Premier League’s most productive attacking full back, and Marouane Fellaini, whom Moyes felt would give United robustness and a plan B perfect for assignments such as West Bromwich Albion and Stoke City.

Fellaini’s buyout clause was £22 million but Woodward had the brainwave that he could get a better deal if he bundled the Belgian together with Baines and submitted a joint bid. Everton, determined to retain Baines, knocked back repeated invitations to name their price for the two players. In the meantime, Fellaini’s buyout clause elapsed.

On deadline day, having finally admitted defeat over Baines, Woodward paid £27 million to make Fellaini United’s only big summer signing. Fellaini, who spent six seasons at United, under three managers, proved a useful acquisition, but on his own was nowhere near enough.

Moyes knew it. United’s 2012-13 title was one of Ferguson’s greatest conjuring acts, won with a patchy and ageing squad. It featured a 39-year-old Ryan Giggs, a 38-year-old Paul Scholes, a 33-year-old Rio Ferdinand and a 30-year-old Nemanja Vidic beginning to suffer the knee issues that would prematurely end his career, plus a clutch of others in their late twenties and early thirties.

There is an oft-reported story about Vidic resenting being shown analysis clips that used Phil Jagielka as an example of how to defend in Moyes’s system – but this did not happen. The story is a fantasy. Though it is true that Moyes banned chips and ketchup from the training ground canteen, upsetting Ferdinand.

“The way I managed and coached was maybe different to Sir Alex. When it all finished I wanted to rethink and relook and work out what I could have done better. How did I present myself?” Moyes told The Sunday Times in November. “The takeaway? It was probably that I felt I had to be more positive. Better communicator. More approachable. I think I’ve always been relatively direct … and I maybe had to be not quite as direct.”

By early December United were ninth, having won only six of their first 15 Premier League games. Moyes found himself labouring round the clock, almost never off the phone, in a grand, dark-panelled office at Carrington still decorated to Ferguson’s specifications. Moyes was impressed by Ferguson’s group of scouts, led by Jim Lawlor, but the recruitment system needed expanding and modernising. It was the same with the medical department and academy.

Woodward was also stepping into big shoes, those of the outgoing chief executive, David Gill, and had some novel ideas, for example that United needed a “fat squad” – ie one comprising a large number of personnel, all tied to longer contracts, so that the playing group was high in asset value. This led to a new five-year-deal for Nani, whom Moyes did not see as important to his plans.

However, slowly, the dial started to shift in terms of squad-building, with Woodward pulling off a coup in January to land Moyes a prime target: Juan Mata. Then, in February, Moyes held talks with Toni Kroos and the pair hit it off. Kroos agreed to join United that summer and the German’s agent, Volker Struth, would later reveal just how close he came to doing so. “The contract and offer were good and Kroos had agreed,” Struth said. “On April 22, they sacked Moyes and we had to start looking for a new club.” Kroos would leave Bayern for Real.

For Moyes, the best thing about his eight months at United was the fans. They offered a level of support he appreciated during a period when, by his own admission, results were not good enough, such as the 2-0 defeat away to Olympiacos, in the first leg of a Champions League round-of-16 tie in February 2014. Woodward took a picture of the scoreboard in Athens and kept the photograph on his desk at Old Trafford, intending it to serve as a reminder of a low point and keep people humble when success returned. In fact, Moyes overturned the deficit, winning the second leg 3-0 to progress into the Champions League last eight. They only once went as far in Europe again during Woodward’s 8 and a half years as executive vice-chairman.

In their quarter-final United pushed Bayern close, leading the tie with 33 minutes remaining. Yet Woodward and the Glazers had had enough, and two days later Woodward met Van Gaal for secret talks. A further 11 days on, United sacked their first manager in 27 years after defeat away to Everton. That reverse made it mathematically impossible for United to qualify for the Champions League, and that meant Moyes was due less in compensation. Another great result for the bottom line. The League Managers Association (LMA) condemned United for a dismissal “handled in an unprofessional manner”.

Moyes had begun his last full day working on a deal to sign Luke Shaw from Southampton. Early in the afternoon his phone lit up with calls and texts from agents and friends – en masse, the newspaper reporters who cover the club were reporting that he was about to be sacked. The tip-off came from high within the club. Woodward refused to meet that evening but confirmed Moyes’s dismissal in a meeting at Carrington the next morning. He told Moyes that the board had started having “a few doubts” after Olympiacos away. Moyes pointed out he had actually turned the tie around, and would have turned United round generally, given time. Woodward said that the team had not shown enough “spirit and fight” to suggest a revival. Moyes noted that if there was one thing he had been associated with, throughout his managerial career, it was producing sides with “spirit and fight”. Was, therefore, the lack of it at United down to the manager? It is a question he left Woodward to ponder.

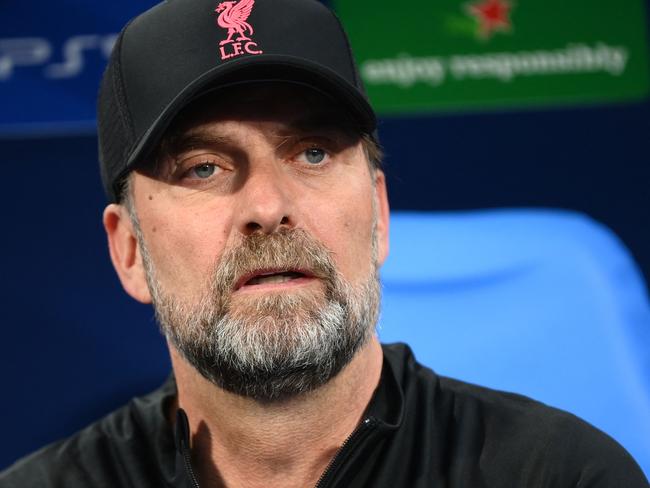

United confirmed Van Gaal as their new manager on May 19, 2014. But when Moyes had departed four weeks previously, the favourite to take over was Jurgen Klopp. Woodward flew to Germany to meet Borussia Dortmund’s then manager and, according to Raphael Honigstein’s definitive Klopp biography, told him that the Theatre of Dreams was “like an adult version of Disneyland”. This sales pitch bemused Klopp, who told a friend he found it a bit “unsexy”. Woodward denies uttering the “Disneyland” line but was known to be “absolutely gutted” when Klopp ended up at Liverpool.

Like Moyes, Van Gaal could not start until July – first he would manage Holland at the 2014 World Cup – but Woodward was convinced that the experienced Dutchman, a Champions League victor and multiple trophy winner in the Netherlands, Spain and Germany, fitted a new template he had drawn up after consulting Ferguson, Sir Bobby Charlton and Bryan Robson.

The template involved four criteria: the manager would play attacking football with X-factor players, draw from United’s academy, be humble off the pitch and arrogant on it.

And Van Gaal believed United was the perfect fit for him. His greatest strength was systematically building clubs and instilling a new identity from the bottom up. To him and Hoek it was obvious this was what United needed. “What Ferguson did is exceptional. When you have a manager like that, who was incredibly responsible for what happened, the moment he retires, everyone who comes after has a difficult job. So what you need is a clear new start,” Hoek said.

“[United] were champions in 2012-13 but the insights I got from the players and staff was that it was a very special championship, because it was not that the team was at the top level, but that everything went in a certain direction. I understood Robin [van Persie] had been very important and everything he touched turned to gold.

“So our understanding was that yes you were the champions, but you have to start at zero, with the fundamentals again. And in my opinion, what I have seen with Louis, at Ajax, AZ Alkmaar, Bayern Munich and Barcelona – when he took over after Johan Cruyff – if anyone is capable of starting again it is Louis.”

Van Gaal’s proscriptive and detailed approach led to culture clashes. He implemented “evaluation sessions” the day after matches where he could be blunt with his appraisal of individuals. Players received emails outlining areas to improve, with video clips attached. Several ignored these, so Van Gaal deployed tracking software to monitor how long emails were opened for – even then, certain players simply opened the emails on their mobile phones and wandered off to do something else. Perhaps this was the start of a dressing-room resistance that Ralf Rangnick encountered.

Van Gaal’s efforts to instruct players on fine details did not always go well. Van Persie did not enjoy being told to make the same near-post run every time the ball came into the box and critics mocked Van Gaal’s “micromanagement” when he instructed Rooney how to take penalties.

However, Rooney would later say that, for tactics and preparation, Van Gaal was “by far the best” manager he played under. Hoek suggests Van Gaal was attempting a culture change that simply needed time. “Louis is a guy who tries to make everything clear and he had quite a few meetings, which is new for players,” Hoek said. “It takes time for players to adjust – but if you are successful it is easy.”

Van Gaal’s start – three wins in ten – was worse than Moyes’s, yet form improved and United finished fourth, ensuring a return to the Champions League. Before his second season, expectation grew after he recruited six new players, including the exciting talents of Memphis Depay and Anthony Martial, and with five victories in seven games United went top of the Premier League. But momentum stalled and the football grew stilted. United would finish fifth, with their lowest goals total (49) since 1989-90.

Once more Woodward was not prepared to wait and began an extended and not-so-secret courtship of Jose Mourinho, who was out of work. Woodward apparently read eight books about Mourinho and canvassed numerous “football people”, becoming convinced that although Mourinho did not necessarily embody United’s precious four criteria, he was a guaranteed winner.

Minutes after winning the 2016 FA Cup at Wembley, news that Van Gaal was about to be fired leaked out. Van Gaal would later say United “put my head in a noose and I was publicly led to the gallows,” describing the manner of his exit as “the biggest disappointment of my career”.

The curiosity is that in the games leading up to the final and in the match itself, United had started winning – and attacking fluently – again. Van Gaal had alighted on a formula that looked to have a future: a new, young front three of Martial, Jesse Lingard and Marcus Rashford, with Rooney supplying from No 10. Hoek believes that had Van Gaal stayed, this unit would have only got better and Depay, who was young and needed to adjust to both England and stardom, would have also come good. But patience was lacking because United’s hierarchy misunderstood the process required to build success.

“It took Klopp four years to win at Liverpool, and [Pep] Guardiola two years to win at City – and that, take it from me, is a miracle. It was only possible because of full support from the top. Knowledge. Football people [in executive roles] who help make it happen,” Hoek said. “That vision has to come from the top – and is what we needed with United.”

Was Van Gaal right to label their former employer “a commercial club"? “I understand what Louis means. United is the biggest club in the world and the commercial department is probably the best. [But] now we’re in 2022 and [in terms of success on the pitch] see where it compares to 2013. Liverpool has been growing, City has been growing and the question is, have United grown? The answer is no. Those are the facts that you can see in front of your eyes.”

‘Very old fashioned. Very bureaucratic. A big surprise.” Within weeks of starting as manager in the summer of 2016, Mourinho had told friends the challenge of bringing trophies to Old Trafford involved far more than reinvigorating a squad in which too many players had grown comfortable with failing to win.

How do you explain one of football’s richest clubs informing the man they had hired to reclaim the Premier League title that one of his key signings could not undergo out-of-hours hydrotherapy in Carrington’s rehabilitation pool because no lifeguard was available to oversee the session?

It was the same story when Mourinho, working long days at United’s training ground, wished to use its gym after hours – not permitted without proper supervision. When he wanted to change his desk in the manager’s office, or gift a signed shirt to a guest, each and every expense, no matter how petty, had to be approved by the club’s hierarchy. Welcome to a Glazer-run company.

Zlatan Ibrahimovic, the forward that Mourinho signed to lead a dysfunctional dressing room by example, was similarly shocked. “Everyone thinks of United as a top club, one of the most powerful, and seen from the outside it looked that way to me,” he wrote last year. “But once I was there I found a small, closed mentality.”

Ibrahimovic cites United deducting £1 from his salary for drinking hotel-room fruit juice on first-team duty; and being “asked to show my papers just to get into the training ground”. “I’d lower my window and say to the person at the gate, ‘Listen my friend I’ve been coming here every day for a month. I’m the best player in the world. If you still don’t recognise me, you’re in the wrong job.’”

Ill-thought-out practice permeated the club. The sports science department would advise on fatigue levels based on sleep questionnaires that some players fabricated answers to. GPS data was deployed to advise footballers to go easy in training sessions – without consulting the coaching staff first. The medical department was another point of conflict.

Overseeing all this was the Glazers’ inexperienced and overconfident chief executive. Woodward’s hesitancy over completing deals meant United lost John Stones to Manchester City and Renato Sanches to Bayern before Mourinho’s first season. The Portuguese had to defuse the contractual bomb that Woodward had created in granting David de Gea an option to join Real in that summer window.

In addition to Ibrahimovic, the other big signing of the Mourinho era was Paul Pogba, who rejoined the club in the summer of 2016 from Juventus for about £90 million. The first season under the Portuguese yielded the two most recent trophies United have won: the League Cup and Europa League. The next year United were Premier League runners-up, albeit 19 points behind City.

It was in 2018-19 that Mourinho’s “third-season syndrome” – his managerial alchemy waning in year three of his tenure, evidenced previously at Chelsea (twice) and Real – appeared to kick in. After missing out on key transfer targets in the summer, two defeats in the first three league games – by Tottenham and away to Brighton & Hove Albion – meant that his side were playing catch-up with the leading teams. After a 1-1 draw with Wolverhampton Wanderers in September 2018, Pogba said that he wanted United to be able to “attack, attack, attack” at home, which led Mourinho to say the France midfielder would no longer be the club’s “second captain”.

Shaw was singled out more than once for public criticism and the player himself acknowledged this in November 2018 as United struggled to make it out of their Champions League group stage. “You need a thick skin to play under this manager,” he said, though added: “But we need to fight for this manager, the team and the club. Everyone in the changing room is a fighter and we want the best for the team.”

There was little sign of that fight a few weeks later when United suffered a 3-1 defeat by Liverpool (the Anfield club had 36 shots to United’s six, with Pogba an unused substitute). The next day Mourinho was out, a development which led to a post saying, “Caption this,” along with a picture of Pogba with a knowing expression, on the Frenchman’s Twitter account before being deleted. The former United captain Gary Neville replied: “You do one as well!” United later claimed it was a “scheduled marketing post” by Pogba’s sponsors Adidas.

At this point in the season, United had 26 points from their first 17 Premier League games, their worst points haul in the top flight at this stage since 1990-91. The hunt for a new manager was on. Again.

As Liverpool humbled United on December 16, Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and his son Elijah were sitting at home in Kristiansund, watching on television – just another pair of long-suffering United fans.

Three days later Solskjaer was sweeping back into Carrington, bearing smiles and hugs and the favourite Norwegian chocolates of the training ground’s legendary receptionist, Kath. Solskjaer had answered a call to be caretaker manager. It would only be until the end of the season, but this was his “dream job” and he was going to spread good vibes.

“I never thought it was going to happen,” he told The Sunday Times, on his return. “I’m just going to enjoy these five months and do the best I can.” His objective was not only to improve results but also “getting players to express themselves. Success for me is improving the team and improving players. It’s about getting the fans smiling.”

He thrashed Cardiff City and Huddersfield Town in his first two games, with Pogba – whom he had managed as a young player in United’s reserve team – especially uplifted. An interaction the morning after the Huddersfield victory stirred in Woodward a notion that he might have stumbled on the golden formula. Woodward walked into Solskjaer’s office to ask how things were going. Fine, Solskjaer replied, but here is what the team might look like in three years.

Solskjaer turned over a flip chart, on which were listed five or six of the existing squad and three young players he hoped the club could recruit, including Hannibal Mejbri, a Tunisian sensation who was 15 at the time, and who United would sign from Monaco. Woodward was blown away.

When United continued to win, leaving Solskjaer with 14 victories from his first 17 games, the sense of momentum became irresistible. Neville epitomised the giddiness of the ex-United players working in the media when he joked that Solskjaer deserved a statue after knocking out Paris Saint-Germain in Europe. Plans to recruit Mauricio Pochettino were ditched. Solskjaer was made permanent manager, on a three-year contract.

He won only two of the season’s 12 remaining games, beginning a pattern that would come to mark his tenure – extended good runs mixed with slumps. The priority of his first summer transfer window was defence, and reinforcing United’s English core, with a remarkable £125 million lavished on Harry Maguire and Aaron Wan-Bissaka. By the time of his first anniversary in charge, United were eighth, but he and Woodward were certain that a “cultural reboot” was taking place.

“We can see things moving in the direction we want and it’s not just on the pitch, it’s what’s happening with the staff at Carrington as well. It’s the mood. The want and need to do your best for the club. The being part of the family,” Solskjaer said.

The message was always a crucial part of his management. Media departments at other clubs noted how United’s manager gave significantly more press conferences and bespoke briefings to journalists than his counterparts. Partly, it was Solskjaer’s unfailing courteousness and accommodating nature. Partly – for he was always a shrewd individual – it was his way of ensuring his giant, perpetually scrutinised organisation spoke with one voice. A Fergie imperative.

Solskjaer had a good 2020. In January he recruited Bruno Fernandes, who transformed United in the second half of the 2019-20 season, and a strong performance after the Covid shutdown yielded third place in the Premier League, as well as FA Cup and Europa League semi-finals. Despite a sluggish start to 2020-21 (which included a 6-1 loss at home to Tottenham), United surged up the Premier League and were top going into the last week of January of 2021.

For Solskjaer, that was as good as it got. Leicester City knocked United out of the FA Cup, while in the Premier League they were overhauled by City. Finishing second equalled the club’s best post-Fergie performance, though, and in the Europa League final in Gdansk the stage was set for Solskjaer to cement himself with a first trophy.

It proved a dispiriting anticlimax. United’s players were lacklustre and Solskjaer struggled with the tactics of Villarreal’s Unai Emery, failing to make a substitution until the 100th minute. Defeat came after a marathon penalty shootout. The lobby who always doubted Solskjaer’s credentials to be an elite club manager took that final as proof he would always fall short at the highest level, and certain players shared those doubts. Woodward, determined to belatedly replicate the loyalty United once showed Ferguson, rewarded Solskjaer with another three-year contract.

There were still plenty of Solskjaer believers, not least that punditocracy of former United players, and after a summer of stellar signings – Jadon Sancho, Raphael Varane and Cristiano Ronaldo – those pundits predicted 2021-22 would be the season United finally challenged for the title again.

And yet Solskjaer lasted only 12 more league games. His dismissal followed a wretched 4-1 defeat away to Watford, which was preceded by eviscerations at Old Trafford by Liverpool and City. On that final day

at Vicarage Road, Woodward and his soon-to-be-successor, Richard Arnold, stayed away – talks with agents about potential replacements for Solskjaer were said to have been going on for several weeks.

Barely 90 minutes had passed since the final whistle at Watford and The Sunday Times was able to break the news that a board meeting was being held to discuss the manager’s dismissal. Officially sacked the next morning, but keen to communicate with supporters until the last, Solskjaer gave a tearful exit interview with club media.

How had it gone so wrong, so quickly? Solskjaer, the ultimate club loyalist, may for ever keep his counsel on events. However, a well-placed source suggests he regretted sanctioning the Ronaldo signing – which had been a club idea, and did not fit with what he was trying to build.

One month into Rangnick’s interim tenure, there came a message from a source closely acquainted with the environment that Solskjaer had needed every ounce of his decency and bonhomie to handle. Results were going OK for Rangnick, but he was already deeply disquieted by performances, the dressing room culture, the deficits in United’s squad and the sheer amount of noise that raged around the club.

To an observation that Rangnick had not taken long to run into the same issues as Solskjaer, the source replied: “It will get worse.”

Rangnick arrived with fierce standards and a reputation in football for club building – but the sheer fecklessness, soullessness and shamelessness of certain elements in the United dressing room shocked him.

“We can only apologise to the supporters. It was a terrible performance and a humiliating defeat,” he said after a 4-0 defeat by Brighton on May 7. Two weeks later he spoke of how he had been unable to get the team to adapt to the pressing game plan that was his speciality and which many thought they needed to embrace.

“We just realised that it was difficult,” Rangnick said. “We had no pre-season, we couldn’t really physically develop and raise the level.”

Rangnick chose not to go into specifics but he could have mentioned: the player who went AWOL from training, returned with profuse apologies, then skipped practice again citing a personal crisis; the player briefing against the club captain, Maguire; the player who continually declared himself unfit to play on the eve of games; the player the coach just could not get through to, because he was so withdrawn; and the player who stood on the burning deck declaring that training should just be fun.

Now the “chosen one” is Ten Hag, and United are trying to learn from the past with the Dutchman joining the day after the club’s 2021-22 season ended, and getting to work on transfers straightaway. Asked about Van Gaal’s ‘commercial club’ criticism ten Hag said “I spoke with the directors. Football is one, two and three at this club and every club these days is commercial. Every club needs the revenues to be at the top … but football is one, two, three at this club.”.

As he strode on to the stage, grinning, to collect the LMA’s manager of the year award the night after ten Hag was unveiled, Jurgen Klopp did not look like a man who rued not being in charge of the “adult Disneyland”. Leave someone else to all that Mickey Mouse jazz.

“This is agony,” Sir Alex Ferguson said as he presented Klopp with his honour. “Absolute agony."

– The Sunday Times

Originally published as How Manchester United crumbled after Sir Alex Ferguson’s exit from the once-mighty club