Leigh Matthews Q&A: Mick McGuane grills his former coach about 1990 Grand Final

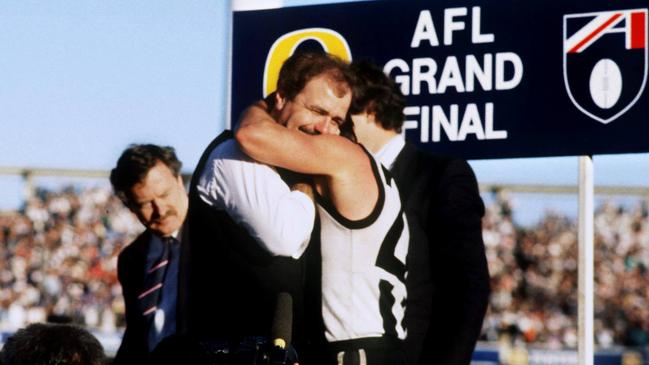

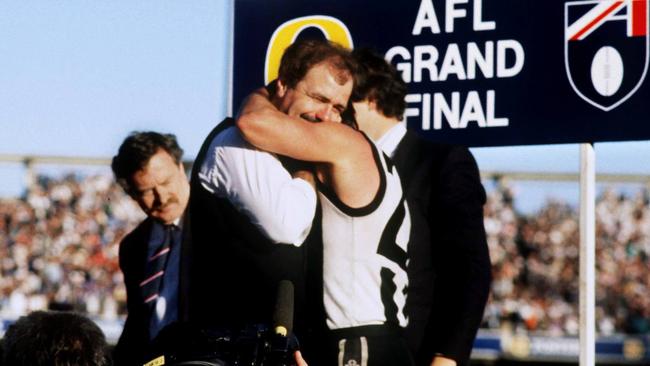

Collingwood’s 1990 Grand Final win was about more than a premiership. The pressure of 38 years of failure was so immense some stars avoided the pre-game parade. And the release after the siren was seismic. Thirty years on, here’s the untold story.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

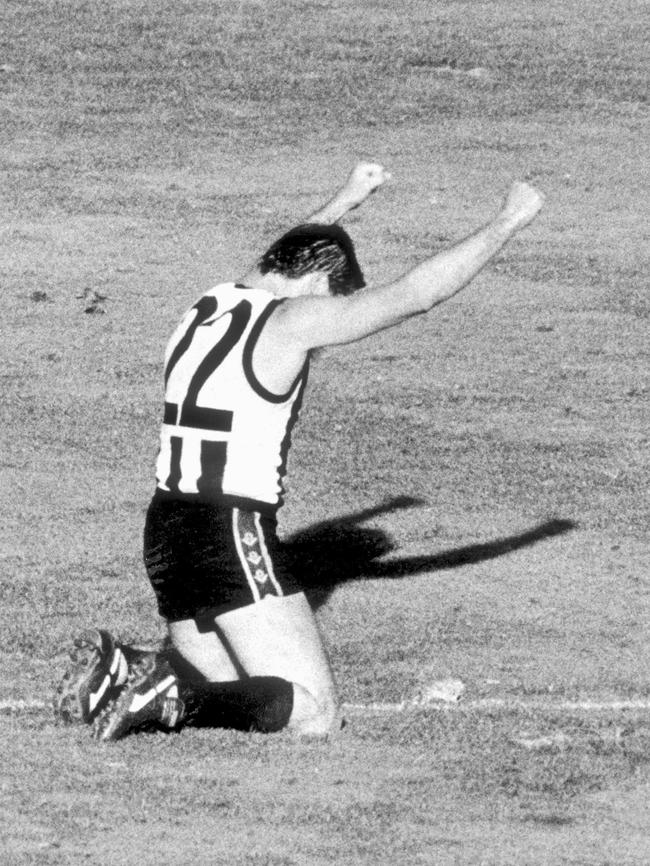

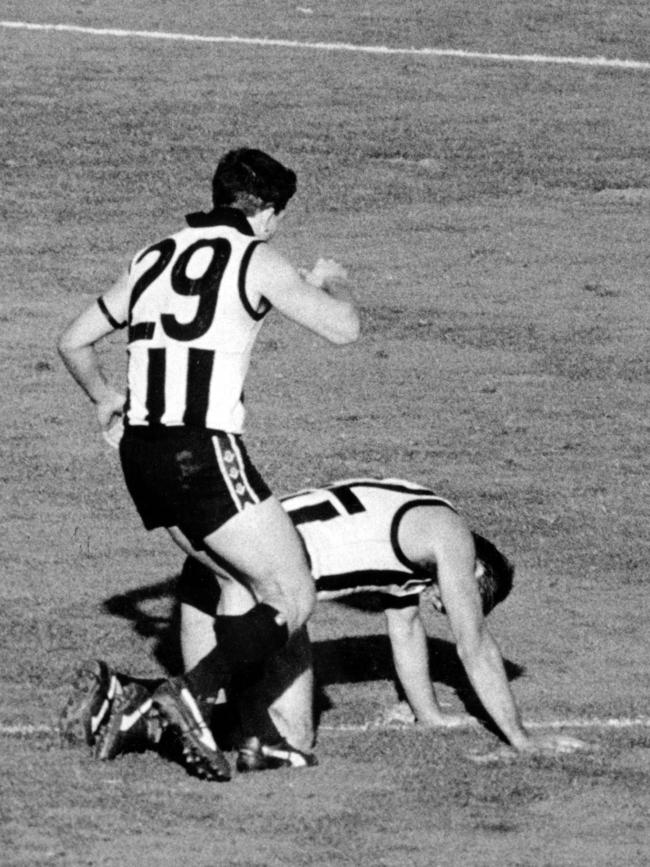

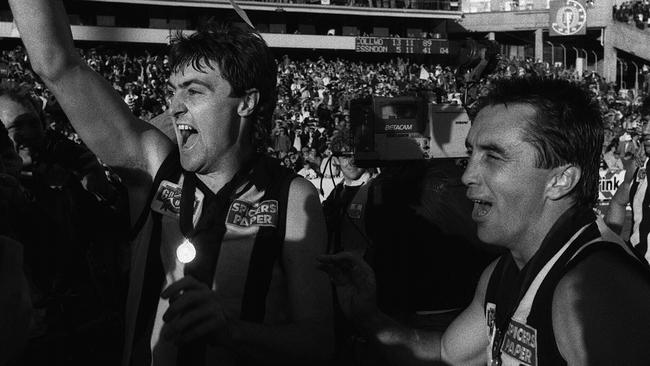

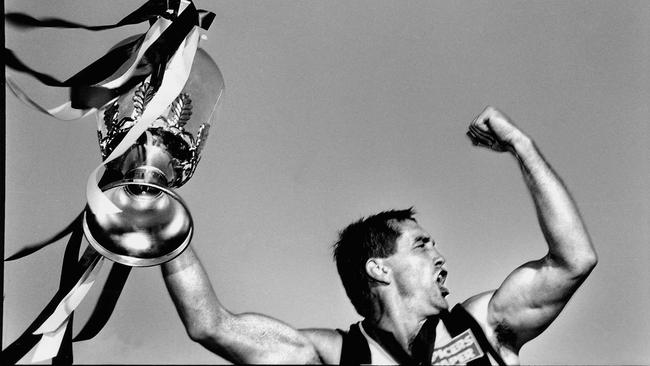

Tony Shaw slumped to the ground on his hands and knees.

Forget elation, this was a feeling of total relief.

Like any Grand Final week, the build-up to the Magpies 1990 premiership win over Essendon had been “massive”.

For Collingwood, it had been a moment 32 years in the making.

When the siren sounded at the MCG as the shadows stretched across the ground, Shaw’s immediate physical response said it all.

“Don’t worry about the excitement, it was just a bloody relief that it was over,” Shaw said.

“I went down on all fours and people said, ‘You were crying’, but I wasn’t crying.

“It was just a bloody relief … it was more a feeling of the pressure’s off.”

Watch the 2020 Toyota AFL Finals Series on Kayo with every game before the Grand Final Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

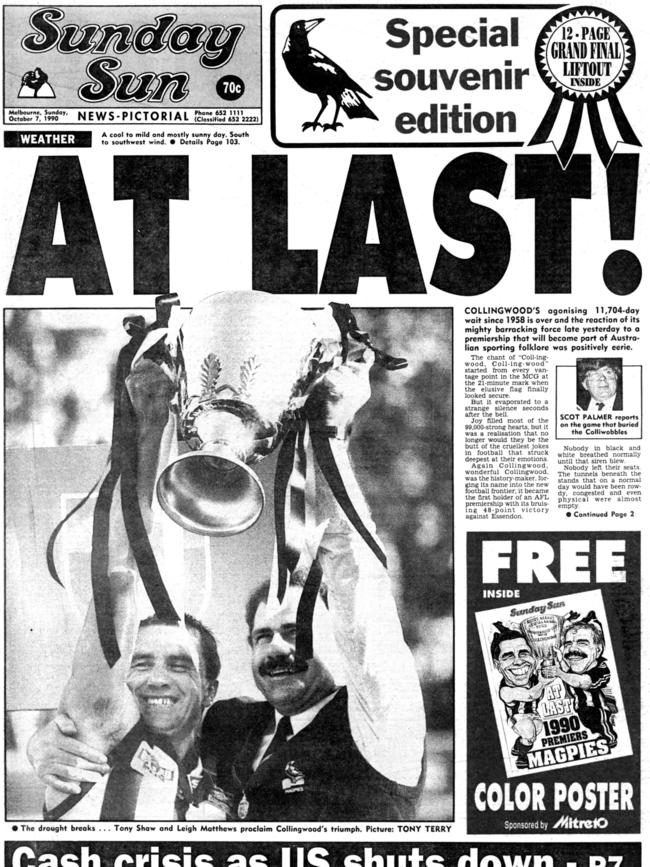

For the Collingwood Football Club, it was pressure which had been building since their last premiership win in 1958.

Since then, the Magpies had featured in nine Grand Finals for eight losses and one draw – in 1977 against North Melbourne.

The margins in four of those Grand Final defeats had been 10 points or fewer.

The team’s extended run of heartbreaking premiership defeats had earned the undesirable tag the “Colliwobbles”, which late club legend Lou Richards had been credited with coining.

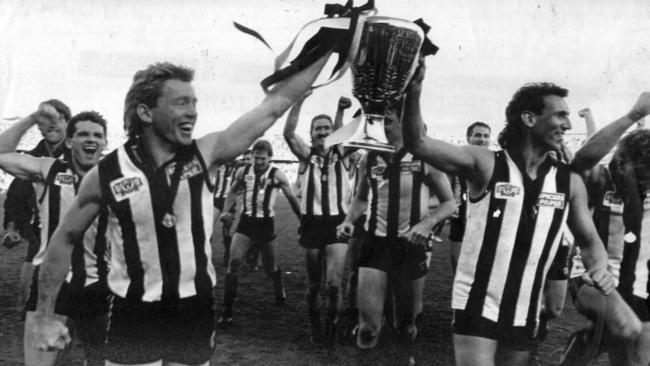

But with their 48-point win over Essendon in 1990, the Magpies emphatically snapped their Grand Final curse – to spell the death of the infamous Colliwobbles.

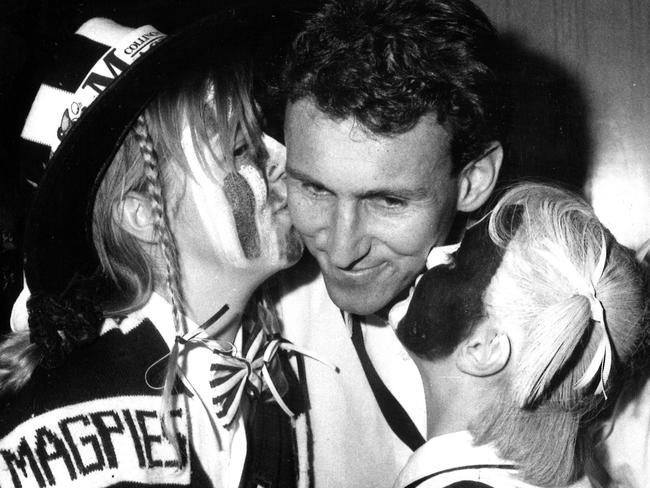

For Magpies captain Shaw, and for many in the Collingwood army who had waited so long to see the famous black and white once again triumph on the biggest stage, this was more than a premiership.

It was a watershed moment in the club’s history, which would thrust the 1990 team into club folklore forever.

The significance of the occasion was magnified for Shaw, who had suffered through Grand Final heartache as a member of the losing 1980 and 1981 Collingwood teams to Richmond and Carlton, alongside his older brother Ray.

“The club just had that stigma of not getting it done when it counted,” said Shaw, who was celebrated as the best player on ground with the Norm Smith Medal in 1990.

“I played in three different eras, in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, so I played with a lot of blokes where we didn’t get it done and I know blokes before my time who were fantastic players and didn’t get it done.

“Even my brother Ray I think played in five losing ones – day and night – so it was really something for the club after 32 years to get off its back.

“After going through a bit of hell early in my career with two losing Grand Finals and finally for the club and everyone to get it done it was pretty special really.”

Star forward Peter Daicos used to get stuck into his mates about the Magpies’ dubious finals reputation as a youngster growing up.

Little did he know he would later experience it himself in his early days in black and white.

It was a brutal early initiation to league football for Daicos at the Magpies, as a member of the team’s losing Grand Final teams in 1980 and 1981.

“As a kid growing up I was a South Melbourne supporter and I was probably one of those that got into my Collingwood mates about the ‘Colliwobbles’ and then all of a sudden I am playing for them,” Daicos said.

“I know how hard they are to win. In ’81 I was 20 years of age and I had played in two (losing) Grand Finals. I played reserves in ’78 but I went back and played in a Grand Final in the under-19s and we lost that.

“In ’79 I played in the night Grand Final to North Melbourne and we lost that. I played in the

’79 reserves Grand Final and we lost that. In 1980, day Grand Final – Richmond – we lost that. Then ’81 Carlton Grand Final, we lost that. So five Grand Finals by the time I’m 20 years of age. We had lost them all.

“I didn’t get another chance until nine years later.”

Older and wiser nine years on, Daicos admits the weight of the Magpies’ finals history had been significant leading into the 1990 premiership decider.

“I didn’t go to the parade on the Friday. I wanted a lot of normality,” Daicos said.

“I didn’t want to get carried away with all that expectation. It was hard to hide from it.

“With that, I say to people, ‘Did I enjoy the week?’ No, I didn’t. I was too worried about the result and getting the game won.”

By halftime on game day, after the dust had settled on one of the great Grand Final brawls of all time, that worry for Daicos had turned to hope.

Hope the Magpies – who were holding a six-goal lead at the main break – were on the cusp of a drought-breaking win.

“We’re not far away here,” Daicos thought to himself in the rooms at halftime.

By the time the siren went, like Shaw, it was a feeling of immense relief for the player they dubbed the Macedonian Marvel who made a career out of brilliant individual feats around goal.

“I think 1990 as a footballer for me is what I hang my hat on,” Daicos said.

“It was huge. You only have to look at what went on after the event. There were cars being upturned in Hoddle Street and 30,000 people were on the ground (at Victoria Park).

“I still run into people on the street, whether I’m getting petrol or groceries, who want to talk about it.

“I went into Coles recently and the checkout lady recognised me and the first thing she tells me is how happy her husband was and how she didn’t see him for three weeks as he was celebrating off with his mates.

“It’s constant, people always bring it up all these years on.”

For Collingwood president Eddie McGuire, the 1990 premiership was a defining moment in the club’s history.

“It recalibrated the club,” McGuire said.

“After ’60, ’64, ’66, ’70, ’77, ’79, ’80, ’81 and preliminary finals and everything that was happening there, we needed to win that one.

“There was all that pain. We lost ’80-81 and then the club sort of blew itself up a bit with Tommy (Hafey) … the promise of the new Magpies and then the club being broke in ’87 and finding itself and with Leigh (Matthews) there, it was just so important to win that game.

“It just made such a massive difference to the club. That was a whole new generation of premiership heroes … the 1958 guys were getting a bit long in the tooth.

“It was one of the most important victories for our club – ever.

“If Collingwood was going to break a 32-year drought after everything, then it happened the right way.”

The month after the drought-breaking premiership win, the Magpies Grand Final curse was officially laid to rest.

A grand funeral procession was held through the streets of Collingwood, winding up at the Magpies’ spiritual home at Victoria Park.

Richards was the funeral celebrant as memories of the Magpies Grand Final defeats were ceremoniously buried under the turf of the club’s home ground.

“All you Collingwood supporters have waited 32 years for this to happen,” Richards told the crowd to huge cheers at Victoria Park.

“We don’t want anyone crying or being sad, this is a very joyous occasion.

“This is the death of Colliwobbles … it’s ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The Colliwobbles are buried and once again it’s them against us.”

It took the Magpies another 12 years to reach a Grand Final and then suffered consecutive losses to the Brisbane Lions in as many years.

The club would not celebrate another premiership until 2010 – and even then it came in a Grand Final replay after a draw against St Kilda.

“It took us another 20 years, we probably didn’t get it done the way that we should have,” Shaw said of ending the team’s Grand Final curse.

Of the Colliwobbles burial, Daicos quipped “they probably didn’t get it into the ground far enough”.

Whether they’ve resurfaced since that famous Grand Final win or not, on October 6, 1990, Shaw, Daicos and Co put the Colliwobbles to rest for one significant day – and that was all that mattered.

WHAT LETHAL SAID IN ‘STUPID’ HALFTIME SPRAY

- Mick McGuane

Footy legend Leigh Matthews has one of the most incredible resumes in the game, and masterminding Collingwood’s drought-breaking 1990 premiership drought is one of his greatest achievements.

He relives the dramatic day with one of the men who helped make it happen, Mick McGuane, including the hardest selection call of his life; the best and worst decisions he has made in a game; the raw courage of Darren Millane; the heartbreak of Alan Richardson; and the celebration of a lifetime including a visit to The Tunnel nightclub.

MICK McGUANE: What’s the one enduring image you have from that day, Leigh?

LEIGH MATTHEWS: It was late in the game when Tony Shaw got the ball on the half-forward flank in front of the old members’ stand, where the coaches’ box was at the time. He turned inside and kicked the ball into Damian Monkhorst. ‘Monky’ went back and kicked the goal from about 30m out. We were about eight goals up with a few minutes to go. That was the moment for me in the coaches’ box when I thought ‘We will win now’, not ‘We probably will win’. We can’t lose now.

MM: Did you feel any extra pressure going into the game, given the external talk about the Colliwobbles?

LM: Yeah, the fact we lost our three finals through ’88 and ’89 (was a talking point) … and you also had Collingwood’s history of playing in so many Grand Finals, and losing. I don’t think it affected what we were doing from day-to-day, week-to-week and from month-to-month. It wasn’t in our thinking. It probably was when Peter Sumich went back in that first qualifying final and had a shot at goal to win the Eagles the game after the siren. When he missed it, and all of a sudden it was a draw, I felt like at least we didn’t lose the game.

RELATED:

1990 GRAND FINAL VILLAIN HAS ‘NO REGRETS’

‘DIRTY’ PIES WIN EPIC PERTH FINAL

THE BT DECISION

MM: How tough was the decision to leave Brian Taylor out of the qualifying final replay?

LM: BT was a terrific full-forward but his knee was shot at that point in time. He actually kicked a couple of goals in that last quarter of the qualifying final to help us draw it. But we made a decision that we had to try and make the team as quick as we could with the personnel we had to choose from. That was the selection strategy, which meant BT lost the position, and I have to say when we were eight goals to two at quarter time in the replay, I thought all of a sudden, it was like the mould had been broken.

THE TOUGHEST CALL

MM: We won the second semi-final against Essendon by 63 points, but it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Was telling Ronnie McKeown on game day that he wasn’t going to play the hardest decision you had to make as a coach?

LM: It was a terrible thing to have to do … basically, I stuffed it up. A couple of hours before the game, I was in the coaches’ room and setting up the basic match-ups as I thought they might work out. Paul Salmon was Essendon’s full-forward and we thought Michael Christian was the best option for him. I put all the names up on the board and all of a sudden there were no real forwards that Ronnie McKeown was going to be suited to.

I thought, ‘What have I done here?’. I said to Gubby Allan, ‘I think I have stuffed up, I think we might have to pull Ronnie out’. You take the deep breath and say don’t turn one mistake into two mistakes. In terms of a judgment call, we had to go with it.

Having to deliver that message to Ronnie McKeown an hour-and-a-half before the game, when he was almost half dressed in his uniform, was about as tough a thing — and as nasty a thing — as I’ve had to do. But you have to do what is best for the team.

MM: What did you say to him? LM: Once you make a call, you have to make it as quick as possible. I brought Ronnie into the coaches’ room. It was pretty hard when Ronnie heard the words, ‘We are going to pull you out at the last minute’. I tried to explain to him what had transpired as best as I could. But it is a very small consolation. I am sure Ronnie McKeown wanted to tell me to go and get stuffed, but he didn’t. He kind of accepted what had happened … and didn’t make a scene at all. That was the mark of Ronnie’s character to accept a really, really difficult decision.

RICHO’S TEST

MM: Alan Richardson broke his collarbone in the second semi-final. Tell us about the fitness test you put him through on the Thursday night before the Grand Final.

LM: I guess I was ruthless enough and callous enough on the team-come-first attitude that I couldn’t believe Richo joined in the training session. I had written him off once he cracked his collarbone. I thought there was no way he would play, but he seemed to join in and was moving his arm and joining in all the ball skills.

There had to be a physical test and I was only five years out of the game. I could do the physical stuff to test him out. I did it a few times. The crowd was watching … they were barracking for Richo, not me. I bumped into him a few times when he wasn’t expecting it. It looked like he still hadn’t broken down. I said to him, ‘Mate, I don’t know, let’s see how you pull up’. He came in before the Grand Final parade and said, ‘I am sore, I am not right’. So he didn’t actually fail a fitness test.

OPERATION PRESSURE

MM: You adopted ‘Operation Pressure’ as the theme leading into the Grand Final. Where did that come from?

LM: That came from my coaching mentor, Allan Jeans. You are always searching for a theme that might consolidate everyone’s attitude. He said when the police force is doing an operation, they give it a name. We came up with Operation Pressure as the key theme. Every coach knows if you can get your team working defensively in chasing, tackling, contesting and pressure, the offence part of the game tends to take care of itself. It was about the pressure you can put on the game, but more importantly the pressure you can put on the opposition. Our tackling effort was the first thing we had to get better than the opposition. We had 52 tackles to Essendon’s 27. That was a lot of tackles 30 years ago.

PANTS’ PAIN

MM: One bloke close to our hearts was ‘Pants’, Darren Millane. He played the last five or six weeks with a broken thumb, but he always said a premiership would be worth the sacrifice. Were you concerned about the risk going into big games?

LM: He broke his thumb in the second-last game (of the home-and-away season). He came to me during the week and he said he had spoken to John Bartlett, the orthopaedic surgeon. The thought was, ‘OK, if we just strap it up and put the painkillers in, we might be able to use it … it means you might have a dysfunctional hand, but you can perform an adequate role’.

He did that on the Thursday before the last game and seemed to handle it. We were like, ‘Let’s give it a go’. He was fair dinkum operating with half a hand, but he was so strong mentally. I always thought Pants sometimes didn’t play the percentages all that well. He was so confident that he would try to do things beyond what he should have.

But this almost gave him a bit more discipline. He knew there were certain things he couldn’t do. He was still an unbelievably valuable contributor on the field. When the painkillers started to wear off, he was in agony. He could hardly put his arm through the shirt of his sleeve, his thumb was that sore. He went through that pain cycle five weeks in a row. You guys all saw that, Mick. It had to be an incredible motivation for his teammates.

MM: He’s been gone for 29 years now. Do you think about him much?LM: It comes up every now and again. It was a life cut very short and an incredibly sad situation.

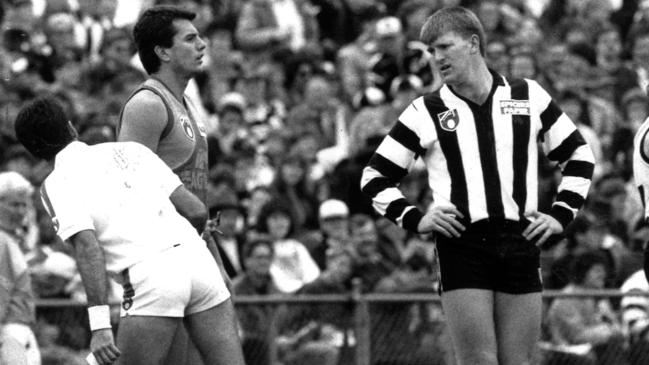

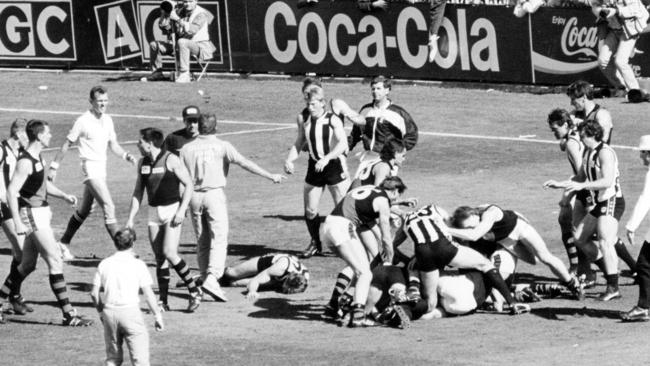

QUARTER-TIME BRAWL

MM: Let’s cut to the game, and go straight to the quarter-time brawl. Was it right that you sent ‘Monky’ over to it?

LM: Now, that was a brawl. We talk on 3AW on the different levels of angst on the field. The highest level is a donnybrook. That was a donnybrook (times) by about 10. You were in the middle of it, Mick. I was down on the ground quickly and the fight was over on the other side of the ground. Monky was on the bench. I said to him ‘Hey Monk, you better go over and see if you can help out’. He has taken off with the dressing gown still flowing behind him.

They were fighting over the Southern Stand side. I looked right and there were officials fighting around centre half-forward. It felt like the whole ground was brawling. When the brawl finally broke up, Gavin Brown had been knocked into next week. He was having medical attention and the rest of the players were coming towards the huddle. I have always heard people talk about players being so fired up that their eyes are rolling in the back of their head. I know that doesn’t happen. But fair dinkum it looked like there were eyeballs rolling in the back of their heads.

A few of the more aggressive players — Darren Millane, Denis Banks and Craig Kelly — looked like wild horses who had been in a stampede. There were two things I knew would happen — the umpires were going to be looking after the blokes keeping their eyes on the ball, and the team that could concentrate on playing the game, not looking for retribution, would be at an advantage.

MM: Your calmness and leadership at quarter-time was important to the group. What was going through your mind?

LM: I guess if you weren’t looking at me when I was talking, I knew I was in trouble. That was a good attitudinal decision. You guys went out in the second term and kicked half a dozen goals and got a couple from 50m penalties. If quarter-time was a good decision, the worst decision I’ve ever made happened at halftime.

THE TD SPRAY

MM: I remember going up the race at halftime and I heard your voice. I thought, ‘Gee, Leigh is emotionally charged’. You had some words with Terry Daniher, who had knocked Browny out. Do you regret that now?

LM: I thought Gavin might have been gone for the day; he definitely would have been today. I kept asking (Collingwood doctor) Shane Conway every 15 minutes, ‘How is he?’ At halftime, both teams came to the same part of the ground and walked up the race next to each other in those days. As Terry walked up, I had Gavin by the arm, and I said, ‘He’ll be back to get you, Terry’.

I did belt a few blokes in my career and I always felt guilty about it. I was hoping I might make Terry feel guilty about knocking Browny out. That was a stupid thing to do because it just could have exploded!

As it turned out, Terry didn’t say much. I turned and walked up the race with Browny, and there was a wire mesh between us. Doing that with Terry was one of the worst decisions I have ever made. Then the decision to walk up the race straight away was one of the best decisions. I did it on the spur of the moment with a purpose in mind but the ramifications could have been terrible.

BREAKING THE DROUGHT

MM: We won the game by 48 points. Then we went to the Southern Cross and later than night got on a bus to Victoria Park. The crowd was incredibly happy. Was that one of your highlights?

LM: The fans are passionate, and that’s fantastic, but to get the job done, you have got to be concentrating on the things to do. I don’t think I would have talked about the winning and losing part before the Grand Final. The premiership is only really valid in the last few minutes of Grand Final day. Up until then, it is about keeping yourself in contention. Late in the game when I came down to the boundary line, there was this “Collingwood, Collingwood, Collingwood” echoing around the stadium. You must have felt that out there, Mick?

MM: It certainly resonated with us. It was like closure in a way. The siren hadn’t gone and we could feed off that. In the last two minutes you could walk past a mate and smile and wink and say, ‘We’ve done this, it’s ours now’. From a players’ perspective back at Victoria Park was great, but getting you to The Tunnel nightclub was something else.

LM: That was my Tunnel debut … my one and only. It was a big night. If you ever felt like a rock star Mick, I reckon it would have been that night. I got down to The Tunnel in one of those open carriages that takes tourists around Melbourne.

MM: It’s lucky a few of the boys didn’t ride the horse down there.

LM: The highlight for me is that unbelievable euphoria at the moment you accept the win. As a coach, you are depending on your players because they are the ones winning or losing the game. You are a bit like a fan because you are not inside that white line. But that hour or so after the game, where you go inside and everyone is in the rooms, that’s the real highlight. You wake up on Sunday morning and the best of it is gone. It’s a nice memory.

MM: What gave you more enjoyment, coaching a premiership team or playing in a premiership team?

LM: They are the only four games that I preferred coaching to playing. The Grand Final wins when you are the coach and your team has got over the line is a combination of euphoria, satisfaction and a release of pressure.

MORE AFL NEWS:

The Tackle: Mark Robinson’s likes and dislikes from the first week of the 2020 AFL Finals

Mick Malthouse analyses where Geelong, Richmond need to improve to bounce back in 2020 finals

Darcy Moore and Adam Treloar on their love for the Pies

AFL semi-finals: Tigers’ Kamdyn McIntosh reveals how modern-day wingers now wear many hats

Originally published as Leigh Matthews Q&A: Mick McGuane grills his former coach about 1990 Grand Final