Eloise Worledge mystery still haunts family

The vanishing of little Eloise Worledge is still shrouded in mystery – and the white lie told by her parents wasn’t the family’s only untruth.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ten years after the Beaumont children vanished from a crowded Adelaide beach, lightning struck again. This time the unthinkable happened in Melbourne’s heartland.

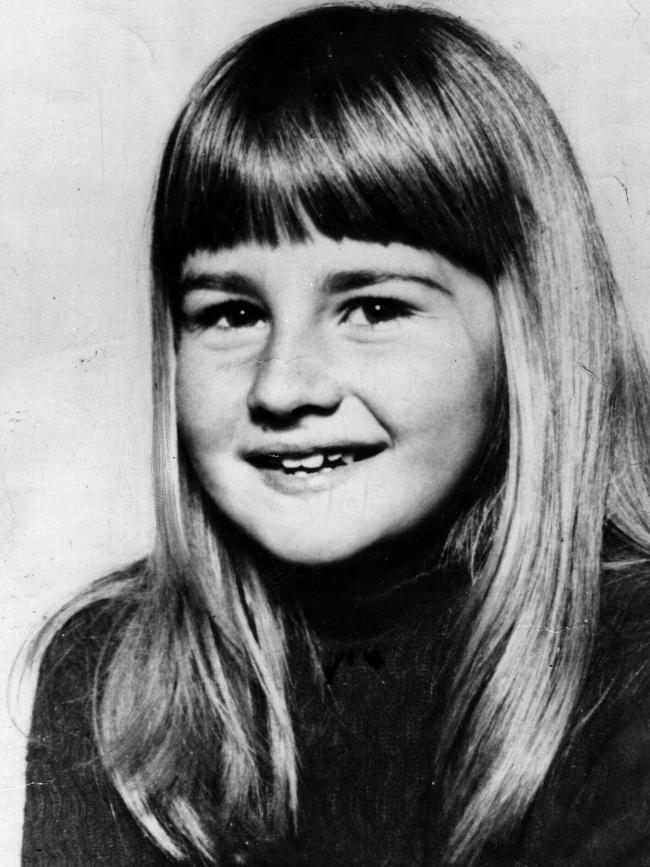

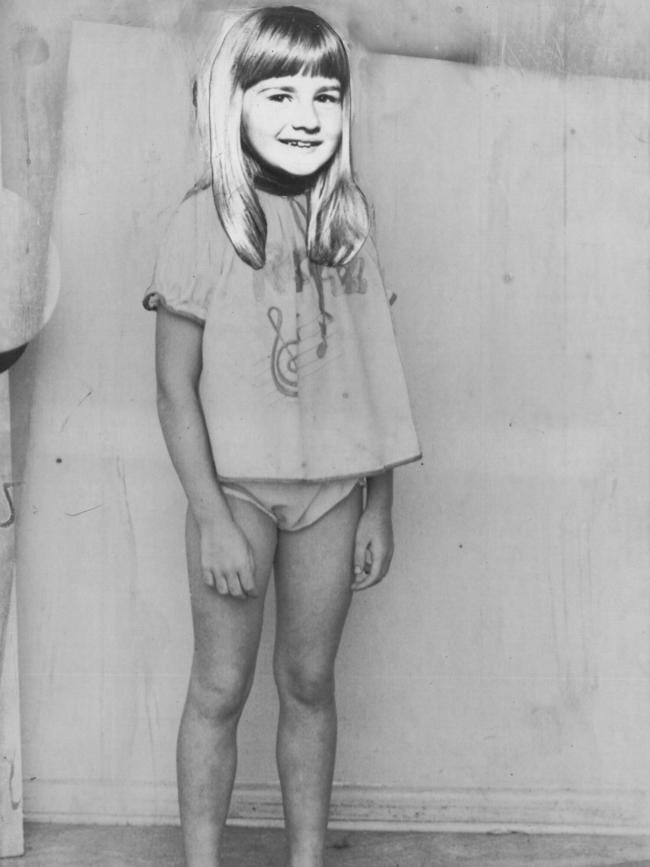

It’s 47 years this week since the night Eloise Worledge disappeared from what seemed to be a normal family home in bayside Beaumaris. She was never seen again.

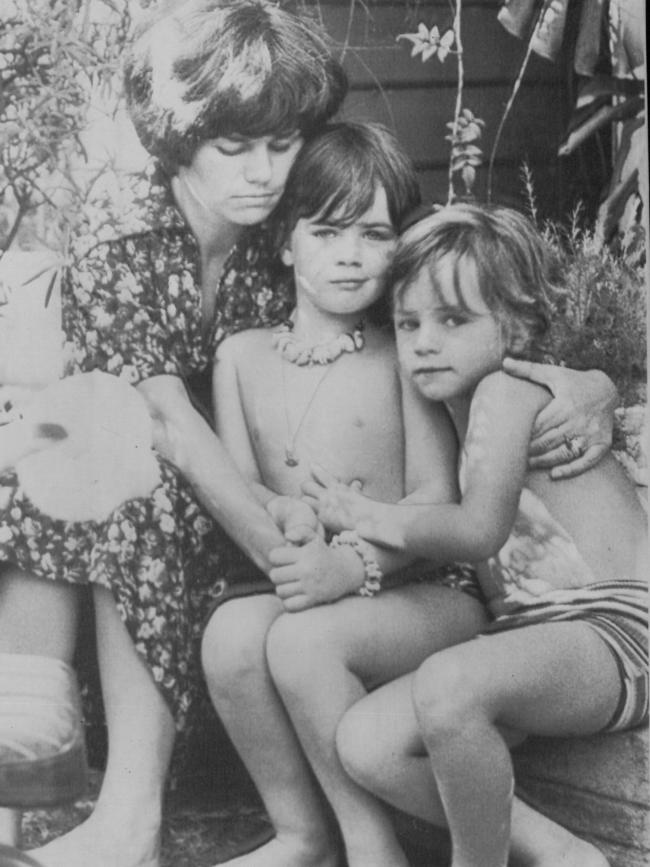

“Ella”, as her family called her, was eight years old, eldest of three children of a couple who appeared to be loving parents and partners shattered by a monstrous crime.

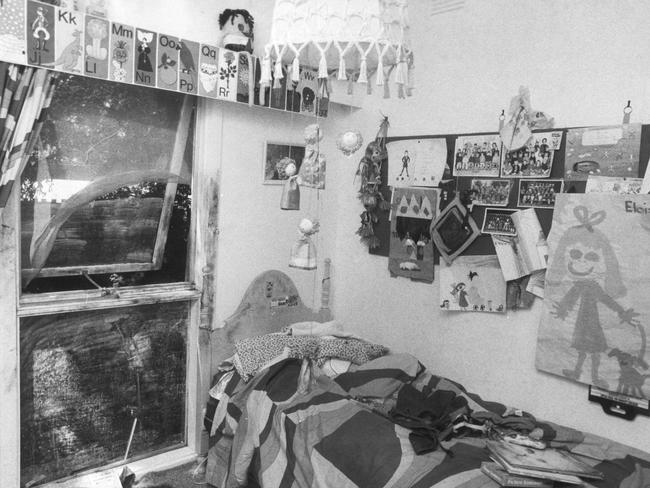

After the initial burst of publicity based on the assumption a kidnapper had stolen Eloise through her bedroom window, police realised that evidence of that was thin.

True, the flywire across the window had been cut and rolled up to make a hole a child might possibly get through. And it was true that a child, even a small adult, might theoretically squeeze through the gap allowed by the wind-out window. But no-one who studied the scene at 46 Scott St quite believed that’s how it happened.

For a start, the flywire had been cut and rolled up from inside. Bits of tanbark on the floor of Eloise’s bedroom looked as if they’d been placed there. Most damningly, dust and cobwebs on the window sill showed no sign of disturbance: no smears or rub marks, let alone finger prints.

Once it was clarified that a thoughtless policeman had stood outside the window in the first frantic hours, it was clear there were no suspect footprints, only the policeman’s.

The almost inevitable conclusion was that the abduction was done from inside the house, the flywire cut as a red herring to divert attention from the fact Eloise had been taken through the unlocked front doorway.

She was a shy, clever child. It was inconceivable she would leave quietly with a stranger, only someone she knew.

Potential witnesses were quizzed over sightings of strangers and strange cars, common in a beachside suburb in summer. But two different neighbours independently confirmed one key point: each had heard a child cry out and a car door slam around 2am on the morning of Tuesday, January 13.

It wasn’t proof but it was close. The odds were that an adult known to Eloise had taken her, then returned to add false clues, the cut flywire and tanbark, to a crime of grotesque cruelty.

The question was, who had a motive to do that? That question hasn’t altered in decades. Neither has the most likely answer.

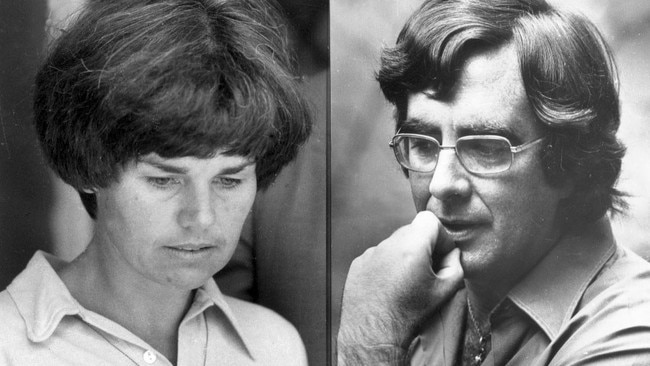

What the public didn’t know was the strange state of affairs in the Worledge household. There were good reasons for secrecy and manipulating the truth about the silent war between Eloise’s parents, Lindsay and Patsy.

The police encouraged the couple, who were bitterly estranged, to promote a false public image. Most reporters co-operated by portraying the Worledges as a happy family to keep the public engaged and sympathetic.

When current affairs host Michael Schildberger broke ranks and asked Lindsay and Patsy on camera if it were true they were splitting up before Eloise’s abduction, Patsy vehemently denied it.

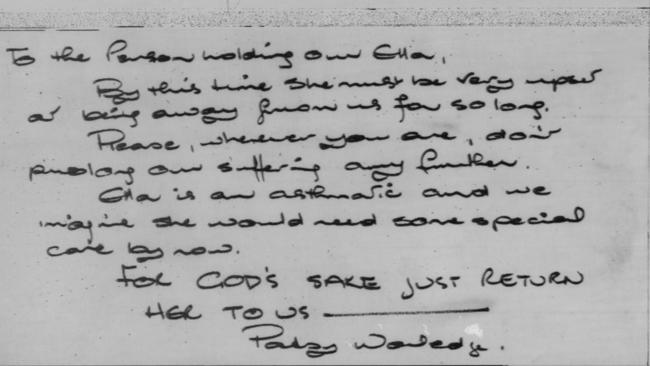

That answer was a lie, told with the best of intentions and the connivance of police, who hoped public empathy would maximise chances of information that might unravel the case.

But Patsy’s white lie was not the only untruth told about the Worledges.

The truth was complicated. Lindsay and Patsy had lived apart under the same roof at least a year, covertly tormenting each other as their marriage of opposites festered into total breakdown. After the abduction, they slept in different houses but pretended not to.

They went through necessary motions in public but, in truth, barely spoke to each other for the rest of their lives.

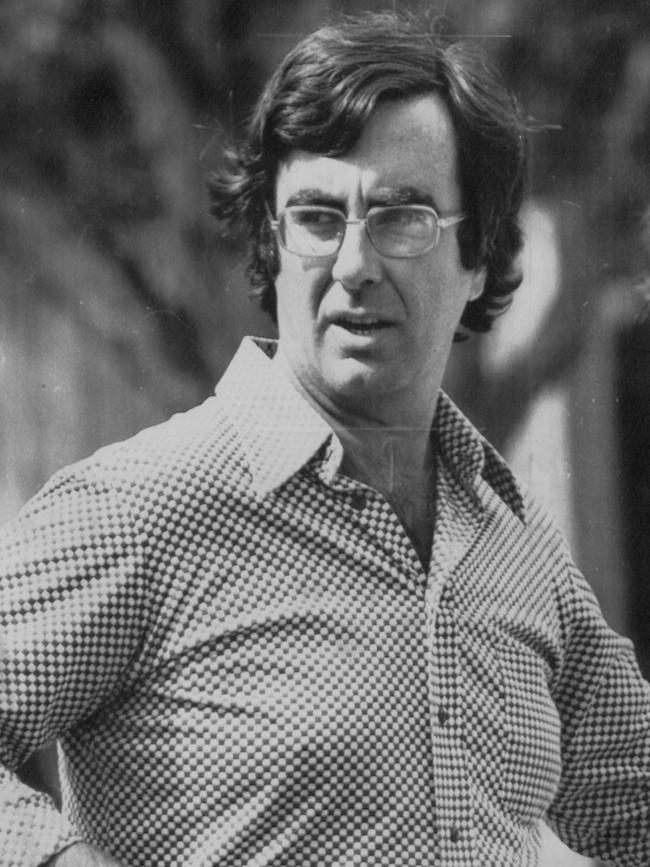

It was strange behaviour for two people who should have been united by the single worst thing that could happen to any parents. Patsy was obviously and understandably anguished — but Lindsay was strangely detached and silent.

To an extent, this reflected their personalities, something that Lindsay’s own family and few friends clung to in trying to explain his unsettling demeanour.

The truth was, Patsy had rebelled against her brooding and domineering husband months before the tragedy, demanding in the previous September that he leave by Christmas, a deadline that had lapsed because Lindsay refused to quit the dead marriage.

Whether he wanted to punish or defy Patsy or felt that a public split shamed him, no one knew. Maybe both.

Patsy was engaging, artistic and playful. She was also strikingly attractive and instinctively flirtatious. In the police euphemisms of the time, she was popular and liked meeting people. Such coded descriptions covered a lot of ground in an era when a new wave of women’s liberation fortified the liberal attitudes of the post-Woodstock era.

Lindsay, by contrast with Patsy, was an introverted intellectual with a grievance and a nasty streak. He thought himself a rung above his wife’s more bohemian choice of “arty, crafty” friends. He had a string of degrees and lectured at the Caulfield Institute of Technology.

Despite differences between them that had grown into deep antipathies, superficially the pair had similar origins.

Patsy grew up in Brighton, Lindsay in nearby Sandringham, oldest son of a hardworking, strictly conservative and religious couple whose unbending attitudes were reflected in him.

Patsy had gone to St Leonard’s girls school in Brighton and Lindsay to its equivalent, Haileybury College. He was a hardworking student, self-absorbed and single-minded.

In an era in which schools were keenly calibrated for social standing, St Leonard’s and Haileybury were a match. The then Patsy Watmuff got together with the suitable Haileybury “boy” when they were tertiary students. They broke up once then married in 1965. Eloise was born in 1967, Annabelle two years later, Blake in 1971.

Flaws became vices. Lindsay’s superior air, possibly masking a sense of inadequacy, meant he was often sarcastic, sometimes cruel. If he’d been drinking, which he increasingly did, it was worse.

Patsy’s faults were not as obvious but friends knew her increasingly risque behaviour and attitude clashed with her husband’s conservative and authoritarian streak.

As became clear to police who interviewed the couple and their family and friends in 1976 (and again in 2001 before a belated inquest), Lindsay had reason to be agitated. He must have suspected that Patsy was conducting multiple affairs, as she had encouraged him to have a one-night stand with her good friend who lived across the street.

Police established that Patsy had a long-term affair with Lindsay’s senior workmate, and had another “fling” with the husband of her best friend. At a function, she had refused to come home with the humiliated Lindsay, preferring to stay out late with a dashing English visitor.

At the time of the abduction, Patsy was already months into the affair with the man who was Lindsay’s boss. The shattering effect of losing her daughter did not end that relationship, which continued via liaisons at friends’ houses until the lover moved in with her later. They split several years later and Patsy remarried the pleasant man she would stay with until his death.

Along the way, she had sought distraction from terrible grief in her own way. The police force buzzed with reports that audio “bugs” placed in the Worledge house recorded a senior detective in a compromising position with the woman he was supposedly supporting. The episode was cited for years at detective training school to warn against the risks of misbehaving in premises under covert surveillance.

For those who knew the Worledges well, the marriage breakdown was a chicken-and-egg puzzle. Had Lindsay drunk more to dull the painful fact his wife not only didn’t love him but actively sought other lovers? Or had Lindsay’s nasty behaviour driven Patsy away from him in the first place?

Either way, it happened. By the time Skyhooks’ Living In The Seventies defined a decade of changing social and sexual attitudes, the Worledges’ marriage was doomed to become a horror story on the 6.30 news of January 13, 1976.

Two nights before Eloise’s disappearance, her brooding father had suffered the calculated humiliation of Patsy holding a birthday party at a neighbour’s without him present because, of course, he was supposed to have moved out by then.

Lindsay would later admit prowling the street to see whose cars were there, to see how many of their mutual friends were at the party. Underneath the controlled mask he wore, it seems, he seethed with uncontrollable resentment.

Two days later, on Monday January 12, he spoke at a business lunch and had some beers afterwards, then came home and drank more, moving from claret to port while Patsy went to a jazz ballet class.

His story, told later, would vary in details but never deviated from the theme that he went to bed late after checking each child was asleep, and awoke next morning to find Eloise gone.

When a new generation of investigators dusted off the file in 2001 to reinterview potential suspects and witnesses, little had changed except the Worledges had suffered another tragedy.

Blake, who as a four-year-old had been first to notice his sister wasn’t in her room, had been killed by a car in 1997. That left only Anna in the bleak space between her parents, by then both remarried.

Patsy rarely spoke of Eloise and never directly accused her ex-husband of an unspeakable crime of revenge. For a long time, says her sister Margie Thomas, Patsy actually hoped it was Lindsay who’d taken Eloise because she clung to the belief he would not hurt his daughter and would eventually return her.

Detectives likewise never overtly accused Lindsay of the crime, but they cleared everyone else whose name came up.

If Worledge had ever been charged, the defence would be justified in claiming that some unknown intruder might have entered the unlocked house that night, drugged Eloise and carried her off. Or that there was an adult on the fringes of the family circle — a teacher or sports coach, say — who knew Eloise well enough that she would trust them.

Of course, a jury might wonder why such a million-to-one thing would happen the very same night that was meant to be Lindsay Worledge’s last hours in the house. That chilling coincidence struck almost everyone who knew the facts.

There are other oddities. Whereas Patsy was understandably frantic with horror, Lindsay was weirdly calm. When Patsy told him to get the police he called the local Beaumaris station, not the central emergency number for D-24.

And when the police answered, he said he wanted to report a burglary in which nothing was stolen “except my daughter”. His lack of urgency and concern rang alarm bells.

Years later, Worledge agreed to a polygraph test. Despite appearing calm at the beginning, he seemed to deliberately sabotage the “lie detector” test with continual movements despite being warned three times it would invalidate any results.

Inevitably, the result was technically “inconclusive” but the test conductor, Steve van Aperen, was confident Worledge had deliberately sabotaged it.

Lindsay Worledge died in 2017, Patsy last year. Her sister Margie has her own thoughts about what happened that night in 1976. But she still nurses the hope that someone knows something that will solve the crime that has haunted her family for almost half a century.

Anyone with information please contact andrew.rule@news.com.au

Originally published as Eloise Worledge mystery still haunts family