CONSIDERING the difficulties and disasters it has weathered in its 120 (now 150) year life, the Northern Territory city of Darwin is remarkably serene, composed and clean.

It has a Territory ambience about it — no one moves too fast in the heat, but there’s usually a warm, smiling greeting from the people there, plus the offer of their hospitality and friendship.

The city centre lies on a narrow peninsular jutting into Darwin Harbor, with the main residential areas for the city’s 75,000 (now 124,000) population to the north. Today, Darwin is a modern city of differing architectural styles. Few of the original buildings have survived its cyclones and wartime bombing.

Government House, built in 1883 and the official residence of the Administrator, is one of those few and even today, amid the concrete, glass and steel of newer buildings, is still the most impressive.

Others to have weathered the times include the former Methodist church in Knuckey Street, old Admiralty House, and Brown’s Mart.

The first British garrisons were established in the area in the 1820s, most being short-lived ventures.

Prior to that time, visitors to the region were Macassans who braved the northern seas to set up trade with the Aborigines — bartering cloth and trinkets in return for bases from which to fish the coastal waters.

The original town, Palmerston, was laid out in 1869.

It was renamed Darwin in 1911.

The South Australian Government, under whose jurisdiction the Territory came, was anxious to develop Asian trade but when this and agriculture development failed to materialise, the town remained only as a link connecting the Overland Telegraph Line, via submarine cable, to the outside world.

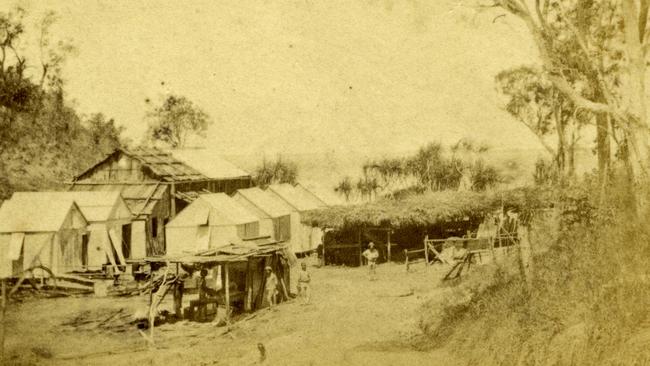

Darwin’s early population was boosted by large numbers of Chinese labourers who came to help build the telegraph line, and to partake in subsequent gold rushes in the Pine Creek area.

The gold, discovery of pearl-shell value, construction of Pine Creek railway in 1889, and the meatworks project of 1920 all helped stimulate growth.

By 1934, the town had expanded to new suburbs of Stuart Park, Parap and Fannie Bay, and in the late 1930s became home to a new RAAF base.

Post-World War II growth was boosted by the Rum Jungle uranium development and other local mineral projects.

And later, in the 1960s and early 1970s, the city was the hub of the Top End — a bustling centre of commercial and administrative activity, its economy and pace enlivened by defence establishments and its servicing of growing rural and urban industries.

But being in a tropical zone, Darwin was — and still is —_ cyclone-prone. The early settlement was flattened by cyclones in 1878, 1882, 1897 and 1937. More recently Cyclone Marcus tore through Darwin.

By far the worst destruction, however, was wrought by Cyclone Tracy in 1974 when the city’s peaceful Christmas Day was wracked by 220k/ph winds which damaged or destroyed more than 90 per cent of the city’s buildings.

More than 50 people were killed, water, electricity, communications and sewerage systems cut.

About 75 per cent of the city’s population of 46,000 was evacuated in a massive airlift in the days following the disaster.

Australia’s greatest relief effort was mounted during those days, with supplies and other assistance flown and shipped in.

From the ill wind of Tracy came, however, the good of a new and vibrant city — one with new and modern-style buildings, its place in 1978 as the seat of the Northern Territory Government, the last of its northern suburbs housing land taken up, and initial planning for the satellite city of Palmerston, some 20km south.

Darwin also has its place in Australian aviation history — the town welcomed Ross and Keith Smith in 1919 after they made the first flight between England and Australia.

The first regular passenger service from England stopped there in 1934 — the airport was granted international status in 1945 — and it was home to the RAAF’s No 75 Hornet-equipped strike squadron, now relocated at Tindal, some 330km south at Katherine.

The city’s other major association with aviation — albeit unwanted — was in 1942 when, for the first time, Australia came under enemy attack.

On February 19, in a repeat of the raid on Pearl Harbor just two months earlier, 188 Japanese aircraft made the first of 64 bombing raids on the city.

Ironically, they were launched from the same Pearl Harbor attack carriers, and were led by the same commander.

In that first raid, an estimated 243 people were killed including 39 civilians.

The post office where 10 civilians died, the police station, airport and many city buildings were destroyed before the Japanese aircraft turned to the harbour where many ships, naval and merchant, were sunk with heavy casualties.

From then until November the following year, the city was target for a further 63 raids.

Those who died are buried in the neatly-maintained Adelaide River cemetery, 70km south, close to where Darwin Hospital was evacuated.

In another Pearl Harbor-like coincidence, a warning of the approaching Japanese raid was given by the Catholic priest on Bathurst Island, across Darwin Harbor, but was ignored.

By 1989 Darwin was a rich and thriving city.

It had an abundance of colourful, well-planned parks and sporting amenities, wide and free-flowing streets, attractive city buildings and tidy suburban homes.

The city’s casino, top-class hotels, low-budget hostels for backpackers, restaurants catered for all tastes, and its diverse retail shops are as interesting for visitors and locals alike.

Cultural amenities included the Darwin Museum and its Beaufort Centre for live theatre and shows. The past was, and still is, remembered in the War Museum at East Point, and the photographic and static display in the old Fannie Bay jail are graphic reminders of Cyclone Tracy.

A major function of Darwin then, and today, is as a springboard for visitors to the many other attractions of the Top End — Kakadu National Park and the Arnhem region, Bathurst and Melville Islands, Litchfield National Park, delightful Katherine and Mataranka.

Today, Darwin is struggling.

Population growth is dropping, longtime businesses are closing, and tourism numbers are down.

But there are positive movements to make Darwin a better city.

A Facebook group is calling for ideas from all on how to improve the Top End, this week Government reannounced its plans to open up more tourist spots in Litchfield National Park, and Chief Minister Michael Gunner looks hopeful for the future (despite the Territory facing some of its biggest debt ever).

With many things up in the air, it will be interesting to see what issues are facing our city in 2089 — or even 2029.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

From the Top End to SA: Untold stories shared in new book on railway history

Russians, railways, bridge thefts, and more – one author’s 20-year project on the untold history of the railways between Darwin and Adelaide has hit the shelves of Territory book stores.

Heart of gold: Life on site at Australia’s most remote mine

With the NT News being given unprecedented access to the Territory’s largest gold mine, take a peek behind the scenes – and meet some of the characters who make the mine tick.