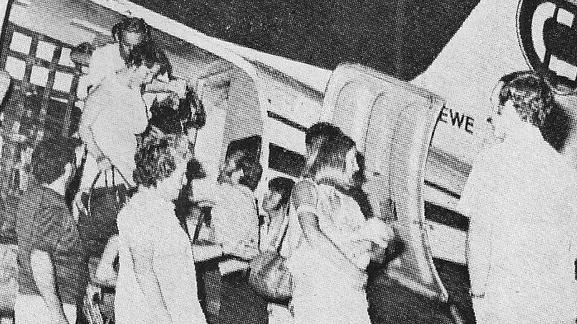

Hours after John Myers passed his captaincy test he touched down at Alice Springs airport.

His cargo: more than two dozen women and children.

They had just flown from a devastated Darwin.

Only 12 hours earlier Mr Myers’ home – which he’d bought weeks prior – had been destroyed in Cyclone Tracy.

He landed in the Red Centre capital at 1.30am on Boxing Day, 1974.

“I’d never seen so many lights and so many vehicles. There were police, there were fire trucks – everyone was there,” Mr Myers recalls.

“Alice had come out in force, not only to see what would happen, but to see how they could help.”

‘These people didn’t look like they had prepared’

Christmas morning of 1974 was unremarkable in Alice Springs.

While most struggle to remember what they did – be it spending time with family, having lunch, opening presents – most can remember where they were when news broke that Cyclone Tracy had flattened Darwin.

By the time the first evacuation flight was due to land in the Red Centre, the whole town knew of the devastation.

Come midnight, the airport was packed, but the true spirit of the Territory shone through – with Centralians eager to help their Top End mates in any way they could.

Among them was former mayor Damien Ryan.

Mr Ryan said he got a call late in the night after hearing about the cyclone.

“They (police) were looking for volunteers … the request for volunteers went out because a plane was coming in from Darwin with the term ‘survivors’ on it,” he says.

“So when it (the plane) landed the door was opened from the inside and there was like a hush (that) went over us.

“Back in the 70s, with aircraft travel, people prepared to travel.

“These people didn’t look like they had prepared.”

Mr Ryan vividly recalls helping a young boy disembark from the plane.

“I just remember this woman passing this young boy, which I presume is her son, to me; I’m on the ground, I grab him, put him down and he screamed,” he says.

“He’s got glass embedded in his feet … that was the [moment] of ‘Hey, something has happened and we’re not fully aware of it’.”

One pilot’s jubilation to devastation on Christmas Day

For John Myers, Christmas Eve was a time of jubilation.

He’d just bought a home on Philip St in Fannie Bay where he was living with his wife and two kids.

The then 29-year-old pilot had just passed his captaincy test with Connellan Airways, and was now fully qualified to fly a DC-3 aircraft – the pride of the airline’s fleet.

But as the celebratory drinks wound down on Christmas Eve, Cyclone Tracy wound up.

By morning, the roof would be gone from his new house, his neighbour's home would be blown away, and the Myers family would spend the night huddled under a large iron bed.

“I put my back against the door and my feet against a wardrobe, braced myself so that I could keep the door shut, which seemed silly seeing the roof had gone,” he says.

“I stayed like that for four hours … the thing I remember most about it was the noise.

“The noise was horrific, absolutely horrific.

“It’s a vivid memory because I honestly didn’t think we’d survive it.”

When the sun came up, David and Franca Frederiksen, friends of the Myers, came and collected them.

While the Myers family was safe, the next step of their journey had just begun.

How help came from the centre of Australia

In the wake of Cyclone Tracy, Alice Springs became a halfway point for those leaving Darwin.

Anzac Oval, in the heart of Alice Springs, was the epicentre of the town’s efforts and the high school – demolished in December 2019 – was turned into an evacuation centre.

Volunteers were providing meals, clothes, and doing laundry for the people who lost everything in Darwin.

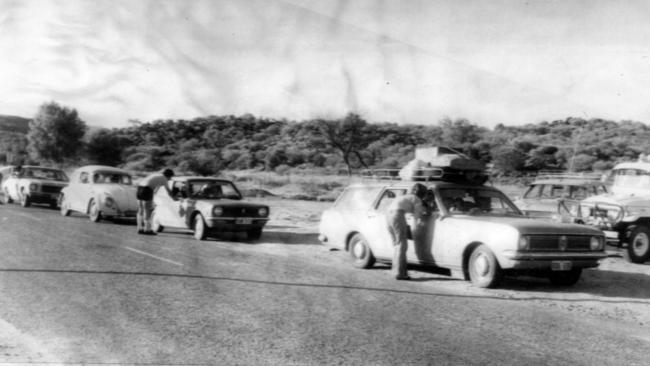

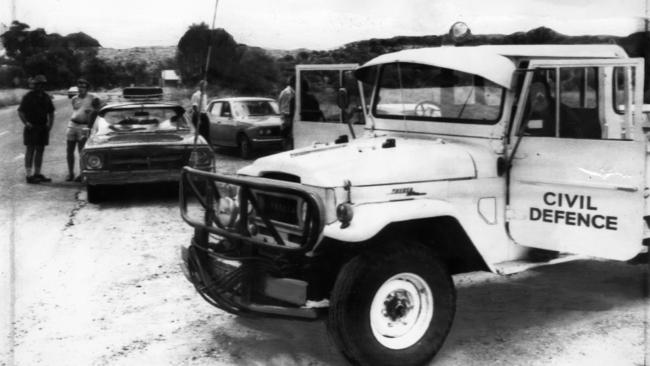

Those who drove down to Alice Springs from the Top End were stopped at checkpoints north of town on the Stuart Hwy.

A separate checkpoint was set up south of Alice Springs to make sure those leaving had adequate supplies.

Many Alice Springs residents manned the checkpoints alongside police, one of them being local man Rod Cramer.

Aged 21 at the time, he was working as an air conditioner technician.

However, once the news broke Tracy had hit the Top End, he realised “We’re not working, we’ve got other things to do”.

“(My boss) decided that we weren’t going to work for the next week and they’d moved the radio base station to the emergency services headquarters,” he says.

Mr Cramer’s boss, Lawrence Coppock, was in possession of something invaluable at the time: HF radios.

The radios proved vital in helping man the checkpoints.

The Alice Springs residents working them helped sort out where to send evacuees to get the help they required on their journey.

“We were all involved in manning those radios and I spent most of the time at the north road one, opposite where the motor vehicle register is,” Mr Cramer says.

As the evacuees had lost everything – such as identification in some cases – Mr Cramer said his job was to record who was coming through.

“They were all still a bit bewildered,” Mr Cramer says.

“I mean, driving from Darwin down to Alice must have been bad enough, let alone the reason they were driving, but then to drive and not know what’s going to happen next …

“You just don’t know how they would’ve been feeling.”

How the ‘worst dressed’ pilots prepared to leave Darwin

Before Cyclone Tracy hit Darwin, Connellan Airways got all of its DC-3 planes to Katherine. The morning after, they made the return journey to Darwin.

Mr Myers had arrived at the airport after a “pretty sorry trip” dodging debris on the road.

Upon arrival at the airport, with the help of Mr Frederiksen, the duo cleared the runway so Connellan aircraft could land.

“It was obvious we had to do something to get all the women and children out of Darwin,” Mr Myers says.

“Not just our families, but everyone needed to be gone, and that’s when it was decided.

“We’d round up the women and children of our own and engineers or anyone else in the staff, and we’d try and get one DC-3s airborne to go to Alice Springs with them.”

Despite only being formally qualified to captain a DC-3 for less than a day, Mr Myers had no hesitation.

Draining fuel out of wrecked planes nearby, Mr Myers was about to make his maiden voyage.

“I had a pair of shorts, some thongs and on the shorts the zip had broken on the fly, a T-shirt and I was probably one of the worst dressed pilots you’d ever come across,” he says.

Accompanying him was Larry Olajos – a Hungarian immigrant who would captain the flight – who was equally dishevelled.

Mr Myers would be the first officer.

His destination, Alice Springs.

But it would require stops along the way to refuel, and he hadn’t slept in 24 hours.

He was about to make the maiden evacuation flight from Darwin after Cyclone Tracy.

A welcoming committee which left visitors stumped – in the right way

From Boxing Day to just after New Year’s Day, the population of Alice Springs had swelled, and the town had come “galloping out the gates to help” Mr Ryan says.

Auto electricians were repairing cars which had barely made it down the Stuart Hwy into town, and those who wanted to go further south were given what they needed to make the more 1500 km to journey to Adelaide.

To Mr Ryan, how much Alice Springs was ready to give was exemplified by the experience one woman – who wasn’t a Tracy evacuee – had in the town.

“She talked after (about) how unbelievable Alice Springs was,” he laughs.

“She drove from Queensland over to Threeways (roadhouse), turned left then came down.

“(When) she got to Alice Springs there was a welcoming committee, they asked whether she needed anything; they looked after her, they gave her fuel, and she nearly got to Port Augusta before she heard about this cyclone.”

In the wake of Tracy, then-Prime Minister Gough Whitlam visited the town, and a telethon, the first in the country, was organised by 8HA radio station in Alice Springs.

It raised more than $200,000 for Tracy victims.

The amount equates to more than $1.9 million today, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s inflation calculator.

To Mr Ryan, the actions of the town in the wake of Cyclone Tracy were merely instinct.

“It’s like if you’re at home in your sandals and pyjamas and the house next door caught on fire – you wouldn’t dress, you’d rush out, you’d see whether there was anything you could do,” he says.

“It was just something you did, it wasn’t something you questioned.”

A trial by evacuation by for a newly minted captain

The first plane to leave Darwin after Cyclone Tracy was a Connellan Airways DC-3.

The plane had a “full load” – 26 women and children – John Myers says.

Piloting the craft was Larry Olajos, Mr Myers was first officer. The duo would take turns flying, while the other would serve food to the evacuees.

But it wasn’t a straightforward journey to Alice Springs, Mr Myers says.

“The DC-3 is a fairly slow old aircraft,” he says.

The journey required them to stop in Katherine and Tennant Creek to refuel.

When they made it to Alice Springs, Mr Myers had been awake for 48 hours. With the town there to greet them, immediately they were swamped with people wanting to know what had happened, and how they could help.

“Everyone wanted to know everything,” he says.

“All the people who’d come, took the families and the children away to their own homes, to look after them, which is good.”

But despite losing his home, barely escaping with his life, and flying a stop start journey from Darwin to Alice Springs, Mr Myers said he couldn’t sleep.

A friend of his, John Cameron, took he and his family in and they spent the next few days recovering.

But his involvement in Tracy wasn’t done – once he’d rested he was back piloting Connellan crafts, doing evacuation flights for the next month.

“I can still recall some of those aircraft evacuation flights out of Darwin in later days, where we had up to 50 people on board, and that may have included 30, 40 children and the rest adults,” he says.

Reflecting on Cyclone Tracy 50 years on

For Mr Myers, every Christmas Day “is a day you think about Cyclone Tracy”.

Originally from Sydney, he’s now living back in NSW.

While he had made visits back to Darwin and kept in touch with some of his fellow Connellan pilots, his involvement in Cyclone Tracy is not something he likes to gloat about. He relates his stoicism on this topic to his father, a WWII veteran.

“He never wanted to talk about the war and most people who come back from war don’t,” he says.

“I think it’s important not to dwell too much on these things.”

In Alice Springs, reflecting on the 50 year milestone, Rod Cramer believes Tracy changed the way the nation viewed cyclones.

“I have no recollection of cyclones being discussed in the same way as, you know, big bushfires, prior to that and some of the big floods that had happened,” he says.

“I think it was a bit of a reality check Australia wide.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout