‘Shooting yourself in the foot’: Tourists question Uluru climb ban

The vast majority of locals support the controversial move to ban people from climbing Uluru, but tourists can’t stop asking one big question.

Travel

Don't miss out on the headlines from Travel. Followed categories will be added to My News.

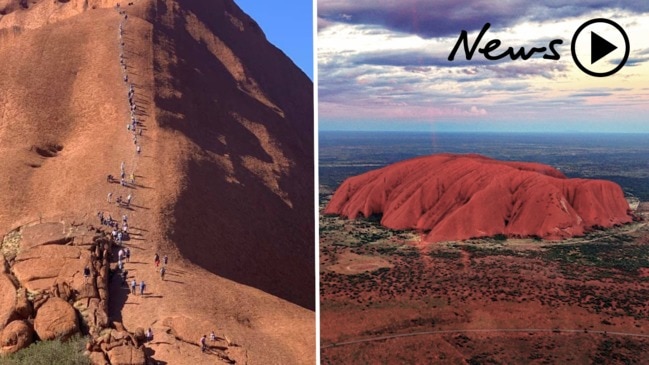

Among some of the tourists rushing to Uluru before climbing it is banned this Saturday, there is bemusement as to why local Indigenous traditional owners would discourage tourist dollars.

The nearby Ayers Rock Resort in the desert oasis town Yulara that was opened in 1984 has been full for most of this year.

That equals close to 5000 people, more than one quarter of who are staff. In fact Australian tourists in cars have camped illegally on private land around Uluru during school holidays because the resort’s campground has been full.

Melbourne tourist Stefan Gangur, 51, echoed the sentiments of other people who opposed the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park board’s decision to impose the ban from October 26 in recognition of the rock’s cultural significance to the Anangu people.

“What are people doing out here? It is part of the economy and how it runs out here” he told AAP.

“You are shooting yourself in the foot, as long as everyone respects it is okay.

“It is no secret a percentage of the money from the national park passes goes back to the Aboriginal people.”

The controversial banning of a rite of passage for generations of Australians since a chain was built in 1964 on the steep western face of the nation’s most famous landmark has prompted warnings that tourism at the nation’s most famous landmark faces an uncertain future.

That chain handhold will be dismantled from October 28.

The park’s general manager Mike Misso says Uluru can now be a better tourist destination with more Anangu people working and benefiting from it.

“The dominant reason for the UNESCO World Heritage listing was the living cultural landscape of nature and culture intertwined through traditions over thousands of years,” he told AAP.

“The closure of the climb enhances the park’s world heritage values. It’s in conflict if you have got inappropriate visitor activity.

“For every tourist destination, you have to reinvent yourself, if you just offer the same people go elsewhere.” Grant Hunt, chief executive at the resort’s operators Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia, says there’s far more to Uluru than the climb and predictions of a significant decline are wrong.

He said there were more than 100 tours and experiences, from riding a mountain bike, segway or walking around the 10km base with interpretative signs to Aboriginal cultural tours, helicopters and skydiving.

Central Land Council chairman and Anangu man Sammy Wilson runs a 4WD tour to his traditional homelands called Patji.

“The travelling public have become much more culturally mature than they were 20 years ago,” Mr Hunt told AAP. “I think most people expect this and in fact want it to happen.

“There’s a minority who still don’t of course and you always get that with any decision but certainly our research and feedback says about 80 per cent of people are supportive of the climb closing.”

While Yulara’s hotels, restaurants and pools are heaving in the high 30C temperatures, the resort has had an “unbelievable run” of average mid-80s per cent occupancy since 2015-16, Mr Hunt said.

That was before the climb closure was announced in 2017 and was driven by cyclical factors: retiring overseas Baby Boomers, a low Australian dollar and innovations such as the Field of Light art installation, he said.

He said bookings in November after the climb’s closure were at a record high: in the mid-90s per cent occupancy for the first three weeks of the month.

But a drop off will occur next year and there is resentment among some of the domestic car and camping travellers about being told they can’t climb a natural landmark.

Some say they have been told the local Mutitjulu community don’t actually mind people climbing.

However a majority of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park board was Anangu when they voted in 2017 to close the climb.

The numbers of climbers back then had dropped to less than 20 per cent with people strong discouraged from doing so over the last 20 years. There should not be too much of a drop in income as the domestic car travellers tended to be a lower yield for tour operators than international tourists.

The biggest drop in foreign visitors should be the Japanese, given they were the most committed to climbing, unlike Europeans who often complained it was still open when Anangu opposed it.

Tourism Central Australia CEO Stephen Schwer said although a few businesses wanted it to stay open the tourism industry, including the 340 members he worked with, mostly wanted the climb closed, “Particularly tourism operators down at the rock because they work with Anangu on a daily basis and they can see the frustration that it causes them,” he told AAP.

“They’re our friends, these are people who are friends with our tourism operators who even in some cases work with them.” Uluru’s cultural and religious significance to the Anangu people relates to Tjukurpa, a word for their creation beliefs and law, which outweighs economic considerations.

The industry also had a responsibility to look after the social, cultural and community values of the destination, as not doing so posed a greater threat to tourism than banning the climb, Mr Schwer said.

There is less wildlife in the region and drinking from waterholes at the bottom of rock because of human waste entering due to people relieving themselves while climbing.

Another issue was that at least 37 climbers have died and people were injured every week, including a 12-year-old South Australian girl who last week fell several metres and was injured.

“Which other attraction, say a theme park or something that’s had over 30 deaths would still be open to this day?” Mr Schwer said.

“People may disagree with putting it in those terms, but from a tourism perspective we’ve got to manage the destination safely. That is unsafe.”

Originally published as ‘Shooting yourself in the foot’: Tourists question Uluru climb ban