Mhelody Polan Bruno, Courtney Herron, Alicia Little - the horrifying thread that connects these women

Research of missing or killed women shows a disturbing trend. Journalist SHERELE MOODY examines the inadequate judicial outcomes failing Australian families and dead women.

Regional News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Regional News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Research of missing or killed women shows a disturbing trend. Journalist SHERELE MOODY examines the inadequate judicial outcomes failing Australian families and dead women.

*Warning: This story contains the images and names of Indigenous women who have been killed.

WHAT VALUE IS A LIFE?

For those who loved her, two things are certain.

Mhelody Polan Bruno will always be their adored generous beauty queen and Australia will always be the country that destroyed their faith in the justice system.

Mhelody was killed by her lover Rian Ross Toyer in the regional NSW city of Wagga Wagga on September 22, 2019.

The facts of the case are simple, but they are also incredibly salacious meaning repeating them causes great pain and heartache for her family.

But — as is necessary when talking about lacklustre judicial outcomes for women from the wrong side of the tracks — these facts must be examined to form an understanding of how the legal machinations set up to hold perpetrators to account so often fail those who no longer have a voice.

Mhelody was a transgender woman from Manilla in the Philippines.

Mhelody’s dad is a farmer eking out a living on the family’s small rural lot in the province of Surigao del Sur.

Her mum is a lowly paid secretary and she has two older brothers and two little sisters.

At 25, the effervescent Mhelody worked hard to support her family.

Mhelody’s main source of income came from her role as a call centre agent in Makati City. She supplemented the money she sent to her family with cash made on the country’s popular beauty pageant circuit.

The beautiful brown-eyed dark-haired woman flew to Australia in August of 2019 to spend time with her long-term boyfriend.

It’s not clear what happened, but the relationship ended.

Shortly after this, Mhelody met Toyer – a 33-year-old corporal in the Royal Australian Air Force.

Around one week before Mhelody was to return home, her family received a video call from her phone.

“I have destroyed her — I am going to give her HIV and I am going to destroy her a*** again,” the man on the phone told them.

They could see Mhelody lying on a bed in the background. She wasn’t moving.

“Sexually explicit and derogatory messages” were allegedly sent from Mhelody’s phone around the same time, an ABC investigation revealed.

The messages included swearing, requests for her friends to send photos of their genitals and claims Mhelody had HIV and that she was “dirty”.

A short time later, paramedics arrived at Tarcutta Street in Wagga Wagga and despite desperate attempts to save her life, Mhelody passed away in hospital.

From the start, there was little hope of Mhelody’s family receiving a just outcome.

Things began to go downhill in the hours after her death as NSW Police set up a special taskforce to investigate the killing.

They called the operation Strike Force Lamson, leading to outrage amongst queer and trans community members – “Lamson” is slang for a sex act that is too disgusting to repeat here.

Toyar was charged with manslaughter and released on bail.

On March 19, 2021, he pleaded guilty, claiming he ended Mhelody’s life by accident and that she died during “consensual rough sex”.

He admitted his lover never verbalised that she wanted him to choke her but he also claimed she never asked for him to stop.

Toyer was given a 22-month intensive corrections order and 500 hours of community service.

Some 10 days after the original sentence was handed down, Wagga Wagga District Court’s Justice Gordon Lerve reconvened the case, sentencing him to 12 months in prison because intensive correction orders could not be imposed following a manslaughter conviction in NSW.

Justice Lerve said Mhelody: “Not only consented to the act of choking but actually instigated it … (the first time the couple) had sex”.

“Although there was no discussion as to the boundaries, there was an understanding the deceased would tap the offender’s arm if she was distressed or wanted him to stop the choking,” he said.

Mhelody’s family disagree with the Justice’s finding, saying it was highly unlikely she would engage in harmful behaviour.

Speaking by phone from the Philippines, Maria Bruno believes Toyar made Mhelody a scapegoat.

The reality is, there’s only two people who know what went on in that room and one of them is dead.

The other is unlikely to waiver from his version of events.

And that’s cold comfort for Mhelody’s family.

“He (Toyer) didn’t ever talk to us,” Maria, a devout Christian, says.

“He did not ask us for forgiveness.

“We do not know if he feels guilty – does he have a conscience?”

The softly-spoken educated young woman tells me through her broken English that she cannot understand how someone convicted over the death of another person can spend so little time behind bars.

“There is no justice for my sister, for our Mhelody,” she says.

“We feel really angry because we cannot do anything to have justice.

“It is so hard, especially as we are in our country and we did not have the people (lawyers) in Australia who could represent Mhelody in court.

“We are so angry that we cannot do anything about it.”

In Australia, the families of people lost to unlawful acts are able to apply for victim’s financial support to help cover the costs of funerals.

Mhelody’s family had no access to this resource as she was not an Australian citizen.

Transgender rights groups organised a GoFundMe to help raise the cash needed to send Mhelody home.

The Gender Centre and other LGBTIQ organisations also sent a letter to the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions, begging the DPP to appeal Toyer’s jail term and saying the decision set a “dangerous precedent”.

“(It) treats violence against transgender women with impunity and further entrenches discriminatory attitudes towards transgender women,” the letter states.

Trans women of colour are more likely to experience repeated sexual assault, violence and harassment compared to other women, a 2020 study published by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety says.

The Gender Centre’s health and communications manager Eloise Brook says Australia’s legal system is weighted in favour of the accused.

Ms Brook says Mhelody’s gender identity was pitted against the “sympathetic presentation of a young man caught up in something regrettable”.

“She didn’t fall into any of the categories of women who are normally protected by the courts,” the academic and activist says.

“He (Toyer) was a man who just needed the court to give him a second chance.

“At the core of this case we can see a disparity exists when it comes to trans women, women of colour and women in general.

“Women who don’t fit the perfect victim narrative have to walk a fine line between what is acceptable and what is not, compared to the reputation and innocence of the men who do these things.”

The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions did not appeal the sentence because “there were insufficient prospects of success”.

“NSW Police laid the charge of manslaughter, which was certified by the Crown Prosecutor briefed in the matter,” a DPP spokesperson says.

“At the sentence hearing, the offender maintained that the death occurred during rough sex … which he was required to establish on the balance of probabilities.

“The sentencing judge accepted the offender’s evidence.

“The prosecution’s position on sentence was that this was nevertheless a serious offence and any sentence other than full-time custody would be inadequate.”

NSW Police were asked about whether or not the investigation into Mhelody’s death was adequate, but their response was short and non-committal.

“Regarding your questions, it is not appropriate for police to provide comment,” a NSW Police spokesperson says.

The Department of Communities and Justice (DJC) also says it could not speak about the case.

“The DCJ does not have any involvement in prosecutions and, as such, would not communicate with any witness or victim in legal proceedings,” a spokesperson says.

Women like Mhelody Bruno are often failed by a justice system that is supposed to be blind.

Unless women are white, young to middle aged and conform to the community’s ideal of the “perfect victim”, the response to her killing may well be tainted by investigations or judicial processes that are far from acceptable to those left behind.

Over the past six years, I’ve researched and documented the killing of around 2500 women and children across the country.

At least 350 unlawful deaths are still before the courts and about 430 suspicious deaths are being investigated or are considered cold cases.

Where people were charged, 45 accused were acquitted at trial, 70 were placed on mental health supervision orders and 210 convicted offenders served — or are serving sentences — of less than 10 years, with the average prison term being six.

In some cases, convicted killers never stepped foot into a prison.

In almost all of the cases where courts delivered unjust outcomes, the victims were from diverse backgrounds – they were Indigenous, trans or queer, multicultural, living with disability or life-limiting illness, poor, homeless, substance affected, unemployed or ageing.

Across the nation, families are outraged by ineffectual police investigations; others are reeling after manifestly inadequate sentences were handed down; and there are those who believe their loved ones would still be alive had violent thugs not been freed by sympathetic courts in the first place.

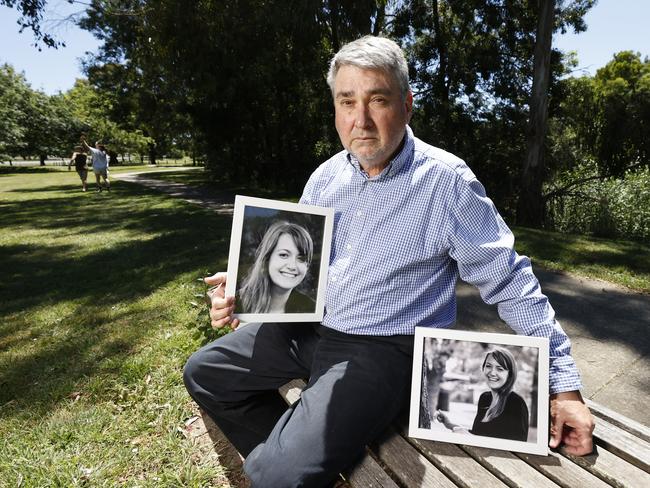

A DAD’S PAIN, A DAUGHTER DEMEANED

Authorities may deny it, but it’s clear police and the judiciary can – and do – profile victims based on their real or perceived “disadvantage”.

The murder of Courtney Herron is a good case in point.

Courtney was killed by a man who should have been in jail after assaulting his former female partner.

When Courtney’s body was discovered, investigators formed a view of her lifestyle that was completely and utterly wrong, her father John Herron says.

We spend some time talking about Courtney, the failings of police and the courts and how he has spent the three-plus years since his life was turned upside down trying to ensure other families of killed Australians are not subjected to unnecessary trauma.

On May 25, 2019, the now 61-year-old Melbourne lawyer found himself in a nightmare that never ends.

Courtney was beaten to death by Henry Richard Hammond at Royal Park, a popular recreation and fitness area in the leafy upper-class Melbourne suburb of Parkville.

At almost every turn, the legal system let Courtney and her family down.

It all started some five or so months before Hammond ended her life.

In December of 2018, he was sentenced to 10 months’ jail for brutalising a woman in an abhorrent domestic violence attack.

Despite an extensive history of violence and ongoing refusals to get help for his drug use and mental health issues, Hammond appealed the sentence on the basis it was excessive.

John says the would-be killer’s repeated attacks on women should have been red flags for anyone in the legal system facing the decision as to whether or not he should be released.

Hammond received a sympathetic appeal outcome, with the court converting his jail term to a 12-month community corrections order.

This, John says, essentially gave Hammond a licence to kill.

We speak about the moment John opened the door to the cops who had come to tell him his daughter was dead.

They insisted – despite his protestations – that Courtney was a drug addict and that she was homeless.

John fervently rejects these claims, saying this perception of his daughter tainted the investigation and that it was made worse when police backgrounded her wrongly to the media.

As police tried to squeeze the 25-year-old former social worker into a certain kind of victim, John had to set aside his grief and anger to protect her reputation.

He says Courtney should have been treated as a human who deserved the strongest judicial outcome, regardless of how she lived her life.

Courtney was the kind of person who would give the shirt off her back for someone in need.

In the hours before he killed her, she was doing Hammond a kindness, yet that information was somehow distorted in the public realm.

“Police tried to make out Courtney was sleeping in the park but she wasn’t – she had a home,” John says.

“People tried to make her look like she was a druggie and homeless.

“On the evening of her death, my daughter bought Hammond dinner, because she felt sorry for him.

“CCTV showed her helping him out but the police were convinced otherwise.

“They had no idea that they had picked on the wrong people.”

Hammond was found not guilty of Courtney’s murder on mental health grounds.

As it was a mental health outcome, John and his family were denied the chance to share their victim impact statements with the court.

“Our voices were not considered,” John says.

Hammond – described by some media outlets as having “model looks” — now resides in the Thomas Embling forensic mental health facility.

Ordered to spend 25 years there, John suspects authorities will deem him safe to return to society in the next few years.

“He could be released without them ever telling us,” John says.

Having spent significant years working for the Victorian Justice Department, John knows exactly how the system works.

He says Thomas Embling inmates spend – on average — four to six years at the maximum security hospital that neighbours scenic parklands in picturesque Fairfield.

When it’s believed the inmates are ready to transition back into the community they are allowed day release, John says.

They are given mobile phones, access to social media and opportunities to socialise at local cafes and shops.

Suppression orders are often used to prevent publication of information surrounding their release so the killers are able to can gain employment unhindered by their past actions.

“These brutes are not being burned at the stake,” John says.

“Every family cottons onto the fact that this process is all about the killers – it’s got nothing to do with the people who were killed.”

John says he has viewed the contents of Hammond’s police file and that alone makes him think Hammond will kill again.

“I do not fear for myself, but given his extensive history of violence I fear he will attack and kill another woman,” he tells me.

“He has learned to game the system.”

A VOICE FOR VICTIMS

Since Courtney’s death, John has taken on an advocacy role for those who believe their loved ones were failed by the legal system.

Right now, the general practice lawyer is working with 12 families in this situation.

With around 65 per cent of his normal legal caseload related to domestic violence, John knows how bad the outcomes can be for women experiencing abuse.

Perhaps one of the most egregious domestic violence-related killings John has faced is the death of Alicia Little.

Alicia was crushed in an horrific act of vehicular brutality by her partner Charles McKenzie Ross Evans at their home in the rural Victorian hamlet of Kyneton on December 28, 2017.

Evans rammed his car into Alicia, jamming her against a water tank before driving over her.

The 42-year-old circus performer died just moments after calling her mum Lee Little to let her know her bags were packed and that she was leaving him.

Lee tells me she heard Evans abusing Alicia during that phone call, recalling with unwavering clarity hearing him say: “Bring your brothers, bring your uncles. I don’t care. I’m a f***ing Evans and I’ll go through the lot of them.”

After killing Alicia, Evans went to a mate’s place where he called her phone repeatedly in a ham-fisted attempt to make an alibi for himself.

He kept up the ruse by telling others Alicia was “alive and well” before eventually claiming she ended her own life.

Evans was charged with murder, but it was downgraded to dangerous driving causing death and failing to render assistance.

If he had been convicted on the original charge, he would have faced a life sentence with a significant non-parole period.

Instead the 48-year-old served just 2.5 years behind bars after accepting a generous plea bargain proffered by the Victorian Department of Public Prosecutions.

I remember distinctly the day Lee found out Evans would plead to the lesser offence.

It was just a few weeks before his sentencing hearing and Lee was struggling to write her victim impact statement.

She wanted to tell the court that Evans repeatedly abused Alicia but she says the DPP told her she was not to talk about that.

We spoke at length about how let down the Little family felt.

Frustrated, angry, sad – Lee fervently told me she wanted more than anything for Evans to be locked up for a significant amount of time.

Cruelly denied this outcome, Lee’s anguish was made worse when the DPP refused to appeal the sentence.

“When someone is killed, you go into the legal system blindfolded – no one tells you anything,” Lee says.

“No one explains what people expect of you and what you’ll have to do.

“They don’t tell you about having to clean-up the crime scene after your daughter is killed.

“They don’t tell you how hard it is to bury her.

“No one tells you how to prepare for when you go to court or how you’ll think you will get justice but then the court gets you and slaps you right in the face.”

Lee believes the families of victims should be allowed to have a lawyer represent them during the plea bargaining and sentencing processes.

“This would mean we could have an advocate making submissions on our behalf and hopefully that would give us an outcome that is just,” she says.

“Until that happens it will never be a justice system – it will only be a legal system that’s there for the defendant, not the victim or their families.”

In December of 2010, Perth mum-of-two Saori Jones was beaten by her martial arts expert husband Bradley Wayne Jones in front of their children.

Instead of seeking help for the critically injured woman, the drunken brute went out.

He came home to find her dead, leaving her body to rot for two weeks.

He was convicted of unlawful assault causing death and spent three years in jail. The maximum term for this offence is 10 years.

He was charged with the lesser offence after he claimed he only hit Saori once.

However, a subsequent investigation revealed he punched her multiple times.

Australia has nine distinct criminal justice systems – one in each state and territory and one at a federal level.

Underpinning the state and territory systems are criminal codes that provide rules about how the courts determine and distribute punishments for offenders.

While every jurisdiction has bespoke crime acts the basic ethos that drives the legal frameworks focus on reducing crime through “deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation”; providing just and fair outcomes for both victims and offenders; punishing offenders based on their crimes while taking into account mitigating circumstances including things like mental health, substance use, age, maturity and previous offending; and ensuring community confidence in the system.

There’s no doubt the judiciary has many complex factors to consider when determining sentences and that most civilians are unaware how these come into play.

As the legal process is centred around the accused, we often learn everything about them because it’s their life stories that are proffered in an attempt to mitigate the final outcome

I’ve spent a good deal of my 30 years in journalism covering courts and can attest to the fact that the personal histories of criminals are presented in minute detail before the magistrate or judge delivers their sentence.

The victims are rarely fleshed out – we may only ever know their age, their relationship to the accused, any previous “history” between the pair including domestic abuse and of course so-called “contributing” factors like substance use.

The people who bring the victims to life are the ones who love them.

They do this by giving impact statements – in some cases, family and friends are able to speak on their victim’s behalf but more often than not their written statements are handed to the judge for consideration without being read out.

Knowing a dead woman’s life story could be vital to changing how courts deliver their outcomes, says Padma Raman, one of Australia’s leading legal minds.

The CEO of Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), Raman has spent her career working across human rights as well as researching the experience of immigrant and Indigenous women under the Australian legal system.

“We know a lot about the offenders,” she says.

“Yet we often do not know anything about the victim, we do not get the stories about their vulnerabilities – about what happened in their lives.

“The criminal justice system is the state taking action against the perpetrator – the victim is often erased in that process.”

This erasure is certainly reflected in the case of Alicia Little. Her family felt her experiences of abuse and her bravery in deciding to leave Evans were not considered when he was sentenced.

And now, it’s too late. All Alicia’s children, siblings and parents can do is hope history never repeats and that their continued advocacy for change might ensure a future victim’s life is considered to be of far more value to the courts.

On his release, Evans moved to NSW where he went about the life of an ordinary bloke, integrating into his local community, even setting up profiles on dating apps.

At the start of 2022, he relocated to Queensland, moving right next door to Alicia’s family.

Evans has served out his parole period and is no longer under the watchful eye of the Department of Corrections.

He has not responded to my repeated requests for an interview.

The Victorian Government acknowledges Alicia and Courtney but it also distances itself from the policing and sentencing outcomes in both cases.

“The deaths of Courtney Herron and Alicia Little are heartbreaking tragedies,” a spokesperson says.

“Our thoughts continue to be with their loved ones as they deal with their grief.

“Sentencing decisions and decisions about whether a person is not guilty because of a mental impairment are a matter for the courts based on the circumstances of each case.

“We continue to work to protect women and children and hold perpetrators to account with an unprecedented investment to end family violence, including $3.5 billion to implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence.”

DEAD, DISCARDED AND DENIED JUSTICE

“But people are oceans – you cannot know them by their surface.”

Poet Beau Taplin’s phrase comes to mind when I think about Shae Francis.

On the surface, the ocean-loving 35-year-old looks like the “perfect victim” – beautiful, young and university educated.

Yet her life was as fraught as it was fragile.

Shae shared an especially close bond with her Aunt Janine Francis.

Janine tells me her intelligent, creative, talented and gifted niece was so determined to help others that she studied human biology at university because she wanted to cure diseases.

Not long before she disappeared, Shae – who was raised in the Victorian regional city of Shepparton — moved to Hervey Bay on Queensland’s Fraser Coast.

Around 245km from Brisbane and a beacon for sea-changers and retirees, the hamlet’s sparkling blue coastline gave Shae the chance to partake one of her passions.

She had a natural affinity for the ocean, often losing herself in the salty water even when the freezing weather turned her lips blue.

Swimming in the sea must have been a sublime escape for Shae, whose housing and health situations were unstable, made worse by the volatility she endured in her three-year relationship with her partner Jason Cooper.

Unemployed and battling an addiction to alcohol, Shae was nevertheless always looking to change her circumstances.

Repeatedly entering detox and rehabilitation programs, she’d be sober for extended periods before getting sucked back into the booze-ridden vortex.

In October of 2018, Shae visited her mother at the Hervey Bay Hospital – this was the last time she had contact with any of her family.

Cooper was keeping them updated – or so they thought – telling them Shae was doing fine at another rehabilitation program.

Most rehab services limit the contact patients have with the outside world, often for months on end, as part of their treatment plans so it’s not surprising that Shae’s family were unperturbed by the fact that she was not communicating.

In March of 2019, her family suspected something was wrong and contacted police.

Cooper hightailed it out of Queensland and was found living in Victoria around eight weeks later. He had Shae’s bank card, Medicare card and her identification.

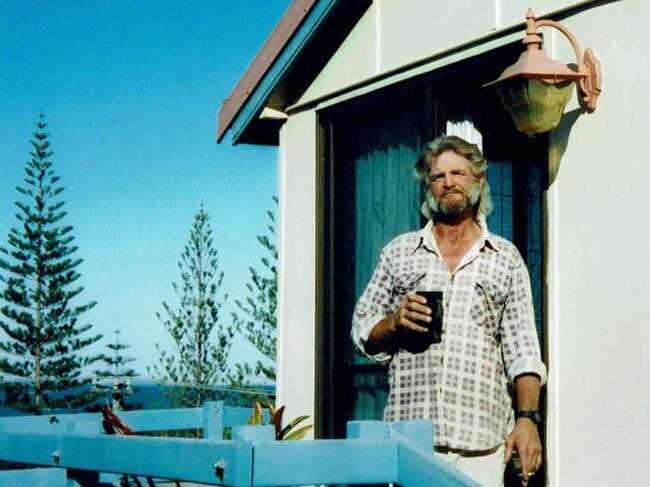

He told cops Shae was alive before changing his story after he was extradited to the Sunshine State and charged with manslaughter and interfering with a corpse.

Cooper pleaded guilty to interfering with a corpse and fraud in November of 2021.

With manslaughter off the table, he was sentenced to two years and five months in jail.

We know that something happened to Shae in the 10 days from October 14 to October 24 of 2018 at the unit she shared with Cooper.

This is what he admitted before he was sentenced in Brisbane District Court on November 26, 2021.

The bearded heavy-set schizophrenic alcoholic says he woke up one morning to find Shae dead.

He says he slept in a small room with her body for three weeks.

Meanwhile, residents noticed a strong smell of decay coming from the unit but no one reached out to cops for two months.

By the time police searched the unit it had been thoroughly cleaned, repainted and readied for new tenants – any evidence was well and truly erased.

Around 21 days after Shae’s death, Cooper “wrapped her in a sleeping bag” and drove her towards a local beach.

He says Shae’s “wish” was to have her remains left by the ocean.

A police car spooked him on the day of the burial so he tossed her into an industrial skip bin that was emptied at a Fraser Coast landfill site. A police search of the rubbish dump failed to find her body.

Cooper admits sending texts to Shae’s loved ones and stealing $9260 from her accounts, spending it on booze and rent.

His admissions were accepted by the court and he is now a free man.

Shae’s aunt has grave concerns about Cooper’s story, believing the dropping of the manslaughter charge is a mistake.

During our interviews, Janine repeatedly asserts Cooper subjected Shae to extreme levels of physical and emotional abuse throughout their three-year relationship.

She says he was on court orders and the abuse was witnessed by people outside of the family circle.

“I saw what she was going through – he would hit her a lot, punch her – he would treat her shocking,” Janine says, revealing a disturbing pattern of coercion, mind games and violence.

“Once he stripped her naked and threw her out in the rain – he threw her into a muddy puddle and she was disorientated.

“A gentleman came and covered her with a blanket and called an ambulance and cops.

“He would have a cigarette and flick it at her – one time her hair caught on fire and he made fun of her.

“She would go into rehab because all she wanted to do was get sober and stay sober.

“She would get out and he would come back into her life.

“He would drink in front of her and coerce her into drinking.

“He’d encourage her more and more and she would pass out.

“He would use her bankcard when she was drunk – he’d take the money without her knowing.”

Shae tried very hard to get her life on track, including leaving Cooper who refused to let her be, Janine asserts.

“She had court orders against him, but he would always win his way back into her life,” she says.

“He was a sociopath and Shae was conditioned to this.

“We’d all think ‘Why? Why would you let him back in your life?’.

“It took me some time to really understand how people become conditioned to the abuse.

“It is not the abuser they end up hating, it’s themselves.

“The abuser is not someone they stop loving – it’s themselves they stop loving.

“Shae thought she was unlovable, unworthy – she was at rock-bottom as far as confidence and esteem goes, when she disappeared.”

Tired, worn out and emotionally fragile, Janine says her niece was denied a voice during the police investigation and the court process.

“Just thinking about the outcome now, I’m tearing up,” she tells me.

“I feel defeated, depleted. I feel exhausted and let down.

“When they withdrew the manslaughter charge – I was totally gutted because the only thing we had to hang onto was the belief that he would be charged and jailed.

“Now we just hold onto the belief that new evidence will come to life and he might be re-charged over her death.

“It took three years for the legal process to finish and we still don’t really know what happened to Shae – we do not know where she is, where her body is.”

Cooper was asked to take part in an interview but he did not respond to the request.

Queensland Police Minister Mark Ryan says the investigation into Shae’s disappearance was undertaken without prejudice towards the victim.

“The investigation was given the highest priority, a Queensland Police Service (QPS) taskforce was established and the case was investigated fully as all suspicious deaths are,” Mr Ryan says.

“The circumstances of the case were unfortunate but ultimately QPS and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions can only go with the evidence that is available.

“Shae’s background or lifestyle had no bearing or reflection on the subsequent police investigation or prosecution of this case.”

Queensland Attorney-General and Minister for Women Shannon Fentiman says she understands the trauma endured by families who feel their loved ones are denied justice.

“Every woman should be treated equally and taken seriously when coming forward to report matters to police and in our courts,” Ms Fentiman says.

“I understand the outcomes of these cases are incredibly upsetting for the victims’ families.

“These matters have been taken seriously by the courts and the DPP.”

The Queensland Government’s Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board examines all family violence deaths in the state to identify patterns, trends and risk factors.

It also reports back to the government its recommendations.

Ms Fentiman says the newly formed Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce – which heard from 700 victims and survivors of domestic and other violence recently – is examining women’s interactions with the legal system.

“A key focus of the review is to examine the responses women receive from our frontline responders and our courts,” she says.

“We are prepared to take action on these serious issues, and we are carefully considering all of the recommendations of the report and will be providing a response soon.”

WHITE JUSTICE FOR BLACK WOMEN

Women of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent experience significantly higher rates of violence than other Australian women.

An ANROWS report reveals Indigenous women are five times more likely to be victims of homicide than non-Indigenous women and they are 35 times more likely to be hospitalised due to acts of family violence.

These are sobering statistics that anyone working in the violence sector knows all too well.

Yet time and again we see courts handing out wholly inadequate jail terms to men who end black women’s lives.

My maternal great grandmother was a strong and proud Gamilaroi woman who married a white man.

Her daughter – my beloved grandmother — part raised me, having a major influence in my formative years.

Like so many other Indigenous woman, she experienced extreme levels of violence at the hands of her husband.

It was only after my grandfather died that my Nan knew peace.

Yet the trauma inflicted by him never eased – she drank herself to oblivion in her final years.

That addiction killed her when I was just 16.

When I think about violence against Indigenous women, I always think of my Nan, whose names I carry.

And I think of the women from our home-country around the Coonamble region of NSW and the abuse and racism they endured.

Researching the deaths of women and children from Indigenous communities is particularly hard because their killings have rarely been recorded in detail publicly.

Even now – in this age of high-speed internet, global connectivity, social media, online coronial and criminal justice archives and digital news gathering – it’s still quite hard to trace their stories.

Of the 104 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims I have documented, almost all of them lived – and died – in central Australia.

And the research shows how unjust the courts have been when sentencing men for some of the most heinous and brutal crimes this nation has seen.

One of those offenders is Trenton Cunningham.

On May 25, 2005, Cunningham bashed his partner to death at the Araru Outstation on the Coburg Peninsula.

The backstory to this act of finality is one that’s reflected in so many of the violent deaths of women of Aboriginal descent.

Cunningham subjected the 27-year-old mother-of-five to unrelenting violence throughout their relationship, including pouring boiling water over her, causing second degree burns to 20 per cent of her body.

She needed significant skin grafts that resulted in “permanent cosmetic deformities”.

He also bashed his partner with a steel bar, breaking her arm and leaving her with extensive bruising.

“If the relationship continues, the end result might well be a fatal injury to (the victim), either deliberate or accidental in nature, or a fatal injury to Cunningham should (the victim) reach the point where she decides to retaliate,” a psychologist says in their sentencing report after Cunningham was convicted on assault charges.

He was ordered to serve 18 months but was released early on the proviso that he not contact his partner.

In late 2004, their relationship resumed.

Some six months later he beat and stomped on her, causing cracked ribs, a ruptured liver and brain damage.

She was expecting her sixth child. The baby could not be saved.

After killing his partner, Cunningham called his mother, telling her: “We had a fight all night and she was screaming for help but no-one came, no-one tried to stop us.”

His mother asked to speak to the victim but he responded: “She’s sleeping mum”.

About half an hour later he rang his mother again, saying: “Mum I think she’s gone. She’s dead.”

Cunningham spent just six years behind bars for ending her life.

“Over many years prior to her death she was the victim of sustained serious and well documented domestic violence from Cunningham,” a coroner said in October of 2006.

“For many months prior to killing his wife, Cunningham’s parole supervision and the enforcement of parole conditions designed to protect his wife from further violence by Community Corrections … was at best perfunctory.”

Neil Nalarra Marika also copped six years for killing his partner.

The 29-year-old mother-of-two was stabbed to death in her home at Cornwallis Circuit in Gray.

Marika, 34, killed the woman while he was the subject of a DVO and not long after he was released from prison for breaching that same DVO.

He had brutalised her throughout their relationship.

Although initially charged with murder, he was convicted of manslaughter and is due to be released in 2024.

On any given day in the Territory, authorities respond to around 61 domestic and family incidents.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows the jurisdiction has the highest victimisation rate for domestic abuse in Australia.

It’s clear something toxic is impacting communities across the NT and it is a problem Kate Worden is prepared to face on.

Appointed in April as the Territory’s first Minister for the Prevention of Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence, Worden says while every community member has a role to play in keeping women and kids safe, the region’s Labor-led government is also committed to turning the tide of violence.

However, she deflected questions about the impact of courts handing out sentences that barely seem to be slaps on the wrist for women killers.

“Decisions of the courts are exactly the court’s decision,” Worden says.

“My focus, and the Territory Government focus, is preventing this violence before it starts.”

The Government will spend $25 million assisting specialist services to support Territorians experiencing domestic, family and sexual violence, she says.

A further $25m is spent each year on prevention, perpetrator intervention and safety and recovery programs and services.

“The government is also conducting a review of the Domestic and Family Violence Act to improve responses to domestic and family violence,” Worden says.

“(It’s) delivering on the Aboriginal Justice Agreement which commits to reducing domestic and family violence offending and is working through a range of actions to this end.”

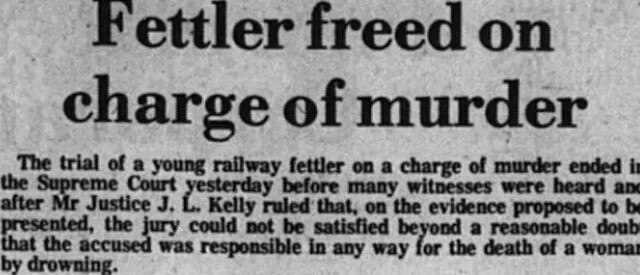

The murder that really stands out as a shining example of how women of colour are let down by the legal system is the killing of Queenie Hart.

In April of 1975, the 28-year-old was raped and left for dead on the banks of the Fitzroy River in the Queensland beef capital of Rockhampton.

The day after she was found tangled in mangroves at Lakes Creek, Steven Henry Kiem – a white man – was charged over Queenie’s death.

On the first day of his trial, a judge tossed out the case saying a jury could not be satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that Kiem was guilty.

Queenie was buried – against her family’s wishes – in an unmarked grave some 450km from her home country of Cherbourg.

In 1978, another central Queensland woman was murdered.

The mum-of-two Margaret Kirstenfeldt was killed in the town of Sarina.

She was partially undressed and her throat had been cut.

Kiem lived very close to the 21-year-old’s home.

After cops connected him to Margaret, he changed his name and moved.

He was never charged over her death but some believe he was responsible because of the similarities between the murders.

Kiem had a long history of violence against women, spending significant time behind bars for a range of offences including brutal acts of domestic abuse.

He died in September of 2019 at the age of 69.

A spotlight has been shone on Queenie over the past few years thanks to a Seven Network podcast, the advocacy of her family and the hard work of journalist and activist Amy McQuire.

After Queenie was killed, media described the perpetrator as a “sadistic murderer”.

By the time Kiem faced a judge, the media had reframed him into a regular hard-working bloke.

Queenie was labelled a sex worker.

“The way they described her, as a prostitute, could not be further from the truth,” Queenie’s sister Lewis Orcher told McQuire in July of 2021.

“I felt what they were doing to Queenie was victim blaming.

“That is one of the things that really hurt, even now when I think about it, it’s really a gross injustice.

“The final indignity of someone who has been grossly murdered. It’s like, ‘Well, you deserve it, you’re a prostitute’.”

McQuire — a Darambul and South Sea Islander woman – says Queenie was defamed and demeaned.

“The man was described by his work, while Queenie was dehumanised,” McQuire writes in The Guardian.

“The coverage of her case was based around the descriptions of her wounds – and she had been wounded and violated.

“But she was held responsible for her own death, not only because of her alleged occupation, but also because she was Aboriginal.

“The newspaper called her ‘coloured’ or ‘dark’.

“There was no mention that she was Wakka Wakka, that she was well-loved, that she was sorely missed.

Back home in Cherbourg, Queenie’s mum Janey Hart was given “few details” about her daughter, McQuire says.

“When Janey tried to get her home to be buried, she was denied permission by the superintendent in Cherbourg,” she writes.

“Janey would never see her daughter returned to her.

“For years, Queenie has been in that unmarked grave in Rockhampton, so far from home.”

Last July, Queenie finally came back to her home country, her community and her family thanks to a crowd-funding project.

“The generosity of people, complete strangers — I am just so grateful,” Queenie’s niece Debbie West told the ABC at the time.

“We may never get justice, but our justice is getting her home to be buried with her family on her own country, Wakka Wakka country.”

WHEN CARERS KILL

During the Disability Royal Commission, Australia heard some harsh truths about the shockingly high rates of domestic and sexual violence against women and girls with disabilities.

We know that 40 per cent of females with disabilities have experienced physical violence; that 90 per cent of women with intellectual disabilities have been sexually abused; and that women with disabilities are twice as likely to be hospitalised due to domestic violence compared to able-bodied women.

Around one woman with a disability is killed every three months in Australia.

In November of 2016, John Frescura shot his partner Janice and their daughter Robyn to death at their home on Queensland’s Fraser Coast.

He also ended his own life.

John was 79 and Janice was 68. She was diagnosed with terminal cancer shortly before she was killed.

Robyn was 50 and suffering from debilitating conditions following a stroke. She also had a brain tumour, but it’s not known if the tumour was life-threatening or survivable.

“The mum’s dying, he’s dying and they have a daughter who is not in a good way,” a neighbour told one media outlet the day after the murders.

“The daughter had a brain tumour and the wife’s just been diagnosed terminal, so I think (a mercy killing) is probably more to the point than domestic violence.

“I would be more along on the assumption that the medical issues were just so overwhelming that he just didn’t see another way out.”

“He just didn’t see a way out”: I read this woman’s comments over and over but I keep coming back to those seven words.

In my time researching murders, I’ve heard every possible euphemism when carers kill.

“Mercy killing.”

“She was suffering.”

“He put her out of her misery.”

These are the kind of tropes that always follows the unlawful deaths of vulnerable women in Australia.

Seemingly loving parents, children or partners end the lives of their loved ones but the murders are not framed as domestic violence – even though these are clear-cut acts of familial abuse.

By taking his own life, Frescura denied the victims and their loved ones any semblance of justice – instead, he became a martyr and they became humans unworthy of life.

I include the murders of Janet and Robyn here because the language used to justify the unjustifiable reveals how far away we are from ensuring the ending of vulnerable women’s lives is seen not as acts of love but as heinous acts of violence.

It’s not just everyday Australians who conflate so-called altruistic killings as acts of love.

Research shows it’s a common theme that permeates the legal system.

NSW Lawyer Frankie Sullivan examined the language used by lawyers and judges in multiple cases across 15 years where Australians were sentenced for ending the lives of the people in their care.

Sullivan found judges often accept the killer’s excuses that the victim’s quality of life was lessened by their disability and that this is seen as a valid reason for the unlawful death.

“… there are entrenched beliefs about disability … that permeate the criminal justice system and perpetuate the disablement of people with disability, with dangerous effects,” Sullivan writes in their 2017 research paper.

“The power of language is particularly evident in sentencing.

“Sentencing is the culmination of the criminal process and the moment at which justice is seen to be done.”

Janene Devine’s husband and sole carer only served six months despite the role he played in ending her life.

The 48-year-old multiple sclerosis sufferer died in in March of 2007, weighing just 30 kilograms – less than the average 10-year-old child.

Janene’s body was covered in bed sores and faeces and she had severe sepsis.

Devine – a registered nurse – refused to let Janene’s sons see her and he also rejected offers of help from authorities after she was repeatedly released from hospital into his care.

In the months before she died, Janene’s mum had one small glimpse of her daughter.

Margaret Cannard told the inquest into Janene’s death that her daughter was unable to communicate, see or even move and that it was clear was totally dependent on her husband.

“She was just like a little frail thing in a bed,” the 88-year-old said.

“Just like a little skeleton.

“There was nothing on her.”

In 2012, the Western Australia coroner ruled Devine should be charged with murder.

Devine was charged with that offence but – as so often happens in cases like this – he pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to 12 months in jail with parole after six months.

“The court wishes you well for your rehabilitation,” Justice Ralph Simmonds told Devine at the end of his hearing.

Devine’s six-month prison sentence is one of rare length in Australia when it comes to carers who kill.

I’ve documented multiple cases of deaths involving women who have disability, are aged and/or suffer from chronic illness and in almost all those charged have walked free without spending a night behind bars.

Janet Lois Mackozdi was 79 when her daughter Jassy Anglin and her son-in-law Michael Anglin forced her to sleep in an uninsulated shipping container on their property at Mt Lloyd in Tasmania.

There were gaps around the windows and doors and the tiny three-bar electric heater they left in the unit could never have emitted the heat to keep the frail woman warm.

It was mid-winter and the temperature in the container fell to minus one degrees.

Weighing just 40kg, Janet was extremely underweight and suffering advanced dementia.

The Anglins were Janet’s primary carers. After she died from hyperthermia in July of 2010, the pair were convicted of manslaughter – a charge that can attract a life sentence in Tasmania.

Neither of them spent time in jail, with their two-year prison terms fully suspended. They were also ordered to pay a $50 victims of crime levy.

Tasmanian Coroner Olivia McTaggart examined the death of Janet.

Janet moved to the Apple Isle three years before she died. She was a “dignified and refined lady” who enjoyed the arts, culture, travel and spending time with her grand kids.

She was very careful with her money, kept her house and personal affairs in good order and led, what the coroner says, was a “simple life”.

Janet was independent until a fall in June of 2009. This, and the impact of worsening dementia, meant she had to be hospitalised.

When she was well enough, she was released into the care of her daughter and son-in-law.

Ms McTaggert says being with the family should have been beneficial for the elderly woman.

She also says Jassy Anglin spent years emotionally controlling her mother, often using threats that included preventing her from spending time with her grandchildren.

Anglin also refused to place Janet in residential care or to get outside services to provide support because Janet “was a source of money” for her.

“I am in no doubt that Mrs Anglin did spend time and energy caring for her mother, although she did so alone and with no adequate medical planning or home support,” the coroner says in her report.

“Mrs Mackozdi did not receive adequate care from Mr and Mrs Anglin and declined in her cognitive state and physical health because of that fact.

“Her physical condition, including the loss of almost one-third of her already low body weight, contributed to her death from hypothermia.

“In my view, the neglect of Mrs Mackozdi’s health and her financial exploitation over an extended period by family members whom she trusted, falls within the definition of elder abuse.”

Gloria Reilly died after she was brutally assaulted by her son Damian Reilly in her home at Geraldton in November of 2011.

The 69-year-old woman had chronic heart and lung disease and was very frail.

Reilly claimed he pushed Gloria down and choked her. He said he left and returned two hours later to find her dead.

Reilly pleaded guilty to endangering life. He was sentenced to one year in jail.

Finding common narratives across cases, Sullivan reveals key themes including killer carers “suffering enough” as the “burden of care” becomes too much, resulting in the perpetrator “snapping under pressure”.

“Having a relationship with people with disability is depicted … as being arduous and oppressive, especially if it involves the provision of assistance,” Sullivan says.

“Flowing on from this, in cases where the offender was also the primary carer of the victim, a narrative emerges in which acts of lethal violence are an inevitable response to the ‘burden’ of care.

“Essentially, the needs of people are cast as so unreasonable and unrelenting that they cause even the most ‘ordinary’ offenders to ‘snap’ in response.

“The mitigating effects of the ‘burden’ of caring … are also evident in the formulation of the sentence, where it is suggested that the offender ‘suffered enough’ through the life and death of the victim and need not be punished.

“By constructing relationships with people with disability as a burden and then invoking narratives in which this burden excuses the offender’s acts, the message sent is clear – disability incites violence.”

Sullivan says “agency, value and quality” must be ascribed to people with disability to ensure a cultural shift that ensures their lives and rights are equal under the law.

Samantha Connor is one of Australia’s leading voices on disability.

Daily she hears stories of appalling abuse – including rape and other violent acts – perpetrated on people who are unable to protect themselves.

She says abysmal sentencing outcomes are symptomatic of policing and judicial systems that fail to reflect the needs of Australians in exceedingly complex relationships with carers.

“When society does not see people with disability as having ‘productive lives’ they don’t get the same sort of media attention and community anger as those women who fit a certain narrative,” Connor says.

“But we also find that because people with disabilities do not fit certain narratives they struggle to get the kind of legal response they need to protect them.

“They may not be able to communicate, for example, and it’s often their carer and abuser who deals with police or lawyers.

“We need police practices that ensure people with disabilities have an independent voice when they need it and that we have supportive decision making in place so they can be believed and be kept safe.

“Our legal systems also need to understand the particular power imbalance that people with disability may experience – often their carers are also their landlord or their partners and this makes it even harder for them to receive appropriate criminal and safety outcomes.”

BLAMING WOMEN FOR THEIR OWN DEATHS

More often than not, courts do jail killers for more than 10 years and quite often for 20 to 25 years – what we call life in Australia.

But that’s cold comfort for the families of dead women whose perpetrators spend significantly less time behind bars than frauds, thieves and low to middle-range drug offenders.

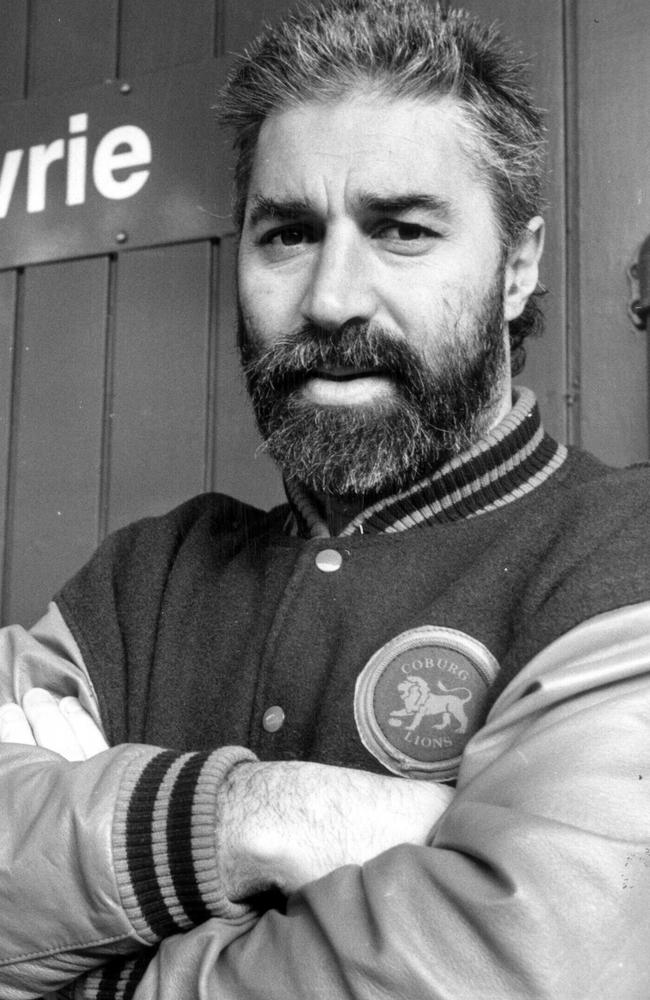

Phil Cleary, a former football star, politician and author, has spent the better part of 35 years trying to ensure women killed as a result of domestic violence receive fair and just responses from Australian courts.

Three decades is a long time on the anti-violence campaign trail where women are often blamed for their murders.

“What was she wearing?”.

“Why was she out late at night on a dark street?”

“She must have pressed his buttons.”

“See what she made him do.”

If it’s been said about a woman lost to violence, Phil’s heard it.

When his sister Vicki Cleary was killed in August of 1987, the perpetrator, his legal team, a jury and a judge put the onus for the end of her life squarely on the 25-year-old victim’s shoulders.

Vicki’s former partner Peter Keogh dragged her from her car moments after she arrived at her workplace in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg.

Wearing rubber gloves and carrying masking tape and a large hunting knife, Keogh stabbed Vicki four times.

He left her bleeding to death in the gutter outside of the kindergarten where she worked. Audaciously, he stopped at a café to get a coffee as he left the area.

It was the final brutal act in a campaign of terror that saw Keogh abuse Vicki during their relationship and then stalk and harass her in the months after she decided to start life over.

She told her family she had no choice but to walk away because her partner was subjecting her to what we now call coercive control – a pattern of intimidating and threatening behaviour that leaves no bruises but results in the victim fearing for their safety and doubting their sanity.

Keogh was charged with murder.

At his trial he was painted as the victim, with the jury accepting his defence that Vicki “provoked” him into killing her because she had left him.

He was acquitted of murder but convicted on the alternate charge of manslaughter and sentenced to six years in jail,

He was a free man after serving just three years and 11 months.

He ended his own life in 2001.

This is where the story should have ended for Vicki – a working class woman from the wrong side of the tracks.

Normally, victims like Vicki are lost to history, but Keogh, the legal system that allowed such a shocking outcome for what was clearly a premeditated and well-thought out killing and the then Victorian Government had no idea how determined her family was to right the wrong.

When Vicki died, Cleary had a huge reputation as a star Aussie rules footballer.

He played 205 games for the Coburg Football Club, kicking some 317 goals. He was pivotal in multiple premierships, captained and coached his team and was also one of Australia’s leading footy commentators.

It would have been easy for Phil to rest on his laurels but someone had to stand up for his sister.

He was not shy about using his status and popularity to change the law.

“After Keogh was sentenced I stood on the steps of the Victorian Supreme Court and I said to the media, this verdict reduces my sister and all women to chattels,” he tells me.

“The system was trampling on women like my sister and I was not going to stand by.

“Vicki should have been just another working class girl murdered by a desperate man, easily forgotten because prejudices do kick in – they would have kicked in.

“But no one counted on her brother being a sporting and media identity with a university degree – someone who was able to articulate so well what was wrong with the system.

“This articulation was so critical to the whole debate about violence against women and how the criminal system responded.”

When Vicki was murdered, Victoria – indeed every Australian jurisdiction – had the defence of provocation in its criminal code.

Provocation could be used by the accused to essentially reduce a murder to manslaughter.

While manslaughter can attract a life term, in many cases the sentence can be much lower – even as little as one year in jail.

For provocation to succeed, the defendant must prove the victim provoked them; that they lost control as a result of those actions; that any ordinary person would also lose control under the circumstances; and that the perpetrator acted due to a lack of self-control during the “heat of passion”.

The defence was most often used by men who killed their current or former partners (hence the term “crime of passion”).

It was also used by men who killed other males because they were “propositioned” to have queer sex.

Provocation is based on a “misogynist narrative” that treats women as though they are the property of husbands, fathers, sons and/or other males in their lives, Phil says.

Misogyny is a lightning rod term used to describe hatred, contempt and prejudice of women – it is also considered a key driver in the toxic attitudes that underpin the social context in which violence against women thrives.

In the late 1980s, ending misogyny often drove the work of many new-wave feminists.

“I believed Vicki’s case and provocation were issues that should have been taken up by the feminist movement,” Phil says.

“It was my acknowledgment that feminists had a part to play in removing the defence.”

It took some eight years before the Cleary family was ultimately successful in changing the law. In 2005, the Victorian Government abolished provocation as a defence, but it can still be used as a consideration in sentencing.

This means jail terms can be considerably shorter if the accused has the right barrister lobbying the right judge for leniency.

The defence no longer operates in Tasmania, WA and South Australia. It still exists in Queensland, although the government there has indicated it will close the loophole.

Both the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory restrict its use.

“Sentencing is really complex,” Padma Raman says.

“There are often so many factors that need to be taken into account and the outcome may not correlate with how serious the crime appears to be.

“When there is drug and alcohol use, mental health, low socio-economic security – all these things might play into the form of sentences delivered.

“If it is a less-than expected sentence, the public message behind that sentence – regardless of how complex the decision – the message might be that the crime was not as serious.

“And that can be a major issue.”

Our Watch is Australia’s bipartisan organisation set up specifically to find ways to prevent violence against women and children.

Patty Kinnersly has led the organisation for seven years, having spent much of her career working across women’s health services.

She says a range of factors contribute to unequal outcomes for women from diverse or disadvantaged backgrounds and that the judicial system must recognise this.

“Men’s violence against women is a national emergency, but not all women experience violence in the same way, or at the same frequency or risk,” Kinnersly says.

“Indigenous women, migrant and refugee women, women with disabilities and LGBTQI people experience alarmingly high rates of violence due to the intersection of gender inequality and other forms of discrimination.

“Racism, ableism, the ongoing impact of colonisation, homophobia and transphobia can contribute to and create a culture where as individuals and communities violence against diverse women is excused or ignored.

“But we cannot look the other way, urgent action is required to end violence against all women, because we know that where women are equal, they are safer.”

Those who work at the frontline of violence say they see the judicial and policing systems failing women experiencing violence every day and this may often include things like “positive discrimination”.

“It is not just the discrimination against the victim if they are marginalised – it is also the positive discrimination for their assailants, especially if they are white or from a middle class background,” Full Stop Foundation CEO Hayley Foster explains.

“We need to look at what other factors are at play and how could they possibly explain that away as though it’s just about the complexity of the judicial system and sentencing practices and precedents?

“You can’t possibly say there’s not that bias in the system.”

Foster believes softer sentences feeds into victim-blaming culture, sending a strong message to the victim, their family and to the community about that person’s worth.

“Is their worth subject to their gender, their cultural background, their socio-economic status, or their sexuality – does that go to the worth of a person?,” she asks.

“When we are talking about the drivers of gender-based violence and domestic homicide I think at the end of the day we have to take into account victim-blaming attitudes that minimise and excuse violence and abuse – that’s what’s being fed into here.

“It is not just the sense that certain victims are not deserving the same sentence because of whatever derogatory reason – it’s about that underlying sense of victim-blaming – that it is something about you that makes you more susceptible to violence or makes it more understandable that the perpetrator behaved the way they did.

“There is that kind of sense of devaluing somebody but also an undertone of victim-blaming – that people because of their circumstances have brought it on themselves.”

But there is hope, Foster says, if police, prosecutors and judicial officers with strong understandings of – and track records in — gendered violence, diversity and societal challenges are given the chance to lead from the front.

“We need to make sure we are appointing people who have a really good understanding and track record when it comes to working with, or presiding over cases, with diverse cohorts,” she says.

“They need to have a strong record for consistency in the work they do and an understanding of the dynamics and the drivers of gender-based violence and the cultural factors such that they are not used as a form of discrimination, but rather as an understanding of context.

“We also need training for these people – when we go into a court room and we are supporting someone, it really matters which judicial officer you get.

“We have really problematic attitudes in the community when it comes to supporting violence so how and when judicial officers issue jury directions to juries, for example, all of that really, really matters.”

News Corp’s Sherele Moody has multiple journalism excellence awards for her work highlighting violence in Australia. Sherele is also an Our Watch fellow, the founder of The RED HEART Campaign and the creator of the Australian Femicide & Child Death Map and All That Remains: The Memorial to Women and Children Lost to Violence.

More Coverage

Originally published as Mhelody Polan Bruno, Courtney Herron, Alicia Little - the horrifying thread that connects these women