NT Senator Malarndirri McCarthy commits to Uluru Statement of the Heart

Australia’s new Indigenous Affairs Assistant Minister brings her journey from remote NT to the walls of Canberra.

SHE walks across Country with the knowledge of Yanyuwa and Garrwa; a woman who finds solace in Li-anthawirryarra (spiritual origin from sea Country).

Newly appointed Assistant Minister for Indigenous Australians and Health Malarndirri McCarthy knows politics is a brutal business.

“I learned from a young age that your sense of self in places that are most foreign is so important to hold on to,” she said.

“I had a wonderful mother who taught me that, and Elders who reminded me; I’ve taken that with me, in every situation of my life, right across the country.”

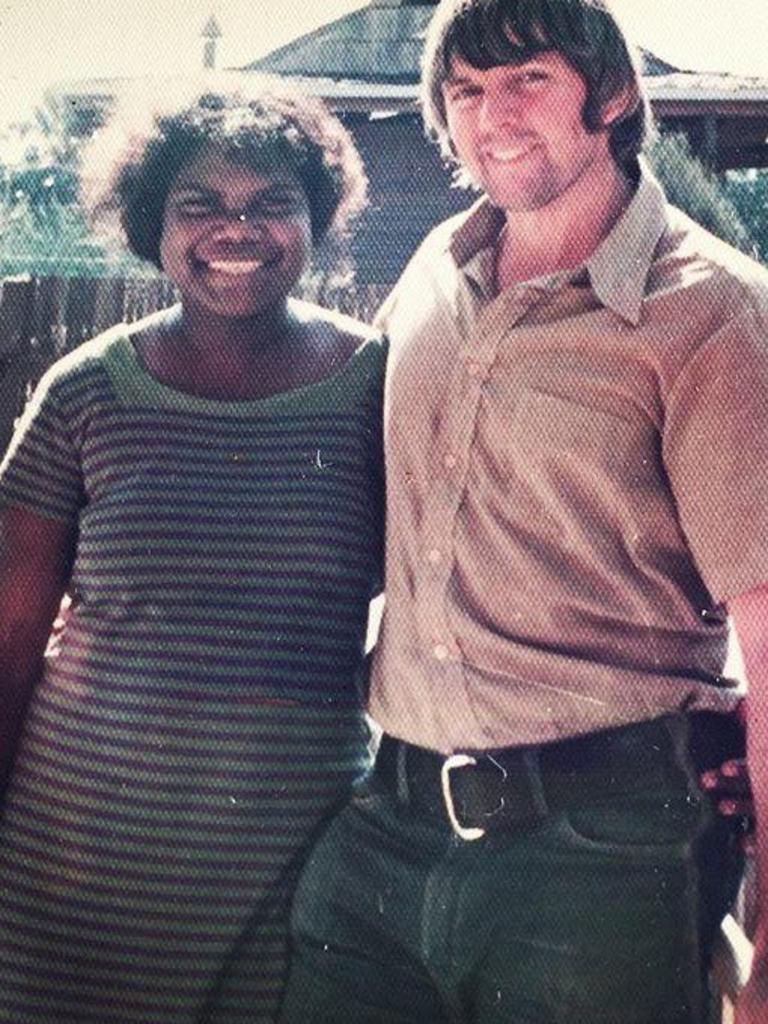

Reflecting on her childhood, she recalls her mother’s strength in knowledge and culture; translating the Bible into Yanyuwa and leading the fight for land rights in their remote home of Borroloola. However, her father’s Irish descent is not lost on her either.

“An early learning for me was how to interact with people from all walks of life,” she said.

Her kinship is clear in the way she now carries herself; from sitting beneath trees in the Territory’s remote Aboriginal communities to carrying those voices into the carpeted, structured halls of the Australian parliament.

First elected to the Senate in 2016, Malarndirri spent her first two terms in opposition under the Morrison government.

“It’s been very tough in opposition because we’ve had to deal with policies that we obviously didn’t agree with,” she said.

“But (Labor) had to show those policies were failing and interrogate them and clearly have a road map as to what we would do differently if we had the chance.”

When the majority Albanese government formed last month, Malarndirri was named an assistant minister alongside the member for Barton, Linda Burney, and her long-time friend, Senator Patrick Dodson.

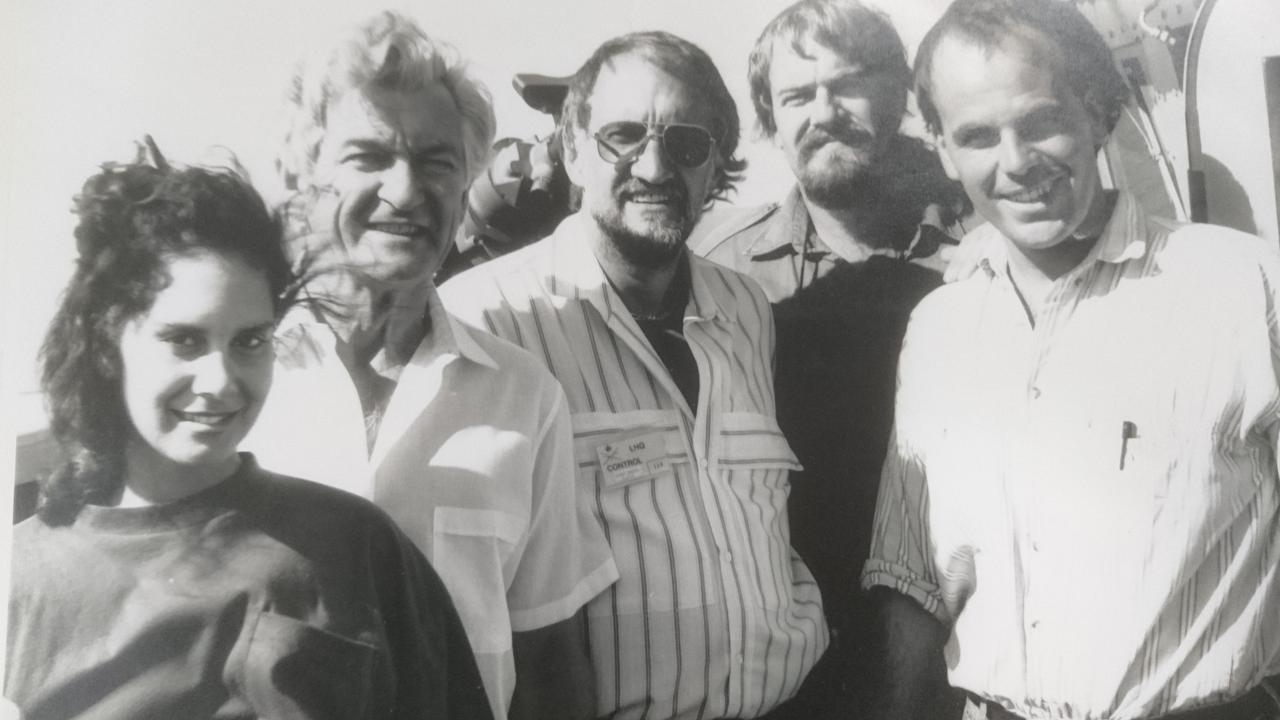

In 1988, she first met Patrick Dodson while doing her journalism cadetship, where she rigorously reported on the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, of which he was one of the commissioners.

“Being a journalist was about trying to tell the stories of the Territory and First Nations people through my eyes, and one of my first gigs was the admission into Aboriginal deaths in custody.

“That was an incredibly difficult time … the reality was Aboriginal people were dying in jails, and listening to the families tell these stories was heartbreaking.”

She reflects that the commission highlighted an “overwhelming sense of injustice” across the country.

However, 31 years later, she and Senator Dodson are now responsible for the pursuit of Voice, Treaty, and Truth as they work to enshrine a constitutionally recognised Voice to Parliament under the Uluru Statement of the Heart.

Malarndirri ’s story appears to move in ripples, each life experience vibrating across waterways and landscapes as she finds new ways to effect change. Her childhood of listening to Dreaming and Kujika (songlines), has led to a lifetime of listening and sharing stories.

Initially a journalist, she worked across the nation, amplifying First Nations’ voices, before the then Northern Territory chief minister Clare Martin is believed to have hand-picked her for the 2005 Territory elections.

For two successive terms as the member for Arnhem, she advocated for First Nations’ rights, memorably crossing the floor to vote against the expansion of the McArthur River mine in her hometown of Borroloola.

“It was a really difficult time then, there was the sorry business of my brother’s passing and then my mother passed (four months later), and I just didn’t feel I had the strength to keep going,” she said.

“The only thing I knew would give me strength was to remember who I am.”

The following year she ran unopposed and was appointed to several ministries, including Children and Families and Women’s Policy.

“My mum was a victim of domestic violence after separating from my dad; it was really difficult supporting her through that at the time,” she said.

“But at the same time family and domestic violence has been very much all around me through many of the women in my family and it’s something that is very real.”

During her time as the Children and Families Minister, Malarndirri said one of her greatest working achievements was the introduction of mandatory reporting for domestic violence.

“I had to oversee that and see that change across the Territory because I knew that we couldn’t have our kids grow up thinking that it was OK for a woman to get hit, or smashed,” she said.

That was a huge piece of legislation that I had to bring into the Territory … it was about changing the culture, not Aboriginal culture but a culture of people thinking that it was OK to walk past someone getting hurt. It’s not OK. It’s never OK.”

As the theme of family expands, the ripple effect grows. Malarndirri’s work at the federal level has focused on strengthening women’s rights.

When asked about her most memorable moment, she pauses for thought.

“I chaired the Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education and carried the report into the Senate in a coolamon,” she said.

“A coolamon is a life-giving thing woman carry – it carries water, food, and babies – and I did that to reflect all the families who have lost children. It was an important moment that led to these families now being able to access paid parental leave, giving them the same rights as anyone who birthed a child.”

When presenting the report in 2018, Malarndirri cradled the coolamon and acknowledged the spirits of those babies who had passed.

She lifted her eyes to the gallery and thanked the families for the courage in sharing their grief which enabled legislative change.

And so the ripples from her own life and the enduring power of Mother have guided her through national change.

Today, that power exists in both her connection to Country and her own family, as a mother of five.

“It doesn’t matter how difficult my situation may have been, there will always be others who are worse off … I think I’ve just carried that and taught my own children, those same values,” she said. Looking to the next challenge – delivering on the First Nations policy Labor has promised, including funding for homelands, justice reinvestment, renal beds, and the Uluru Statement of the Heart, Malarndirri carries the weight of hope.

“Hope can be a very powerful thing,” she said.

“I think my role is ensuring that our social policies do not get forgotten: Closing the Gap, ensuring that housing is improved in remote communities and homelands, the 500 First Nations’ health workers, and working with the health department so that does occur.”

Her own experience with her mum – who passed after a decade-long battle with kidney disease – ignites a passion to improve dialysis services across the country, but particularly for remote Territorians.

While the next four years have given many First Nations people in Australia hope, the work and action are yet to be seen.

“I feel my responsibility in Canberra is to work with my colleagues to push an agenda of health, employment, housing,” she said, “along with a push for freedom.”