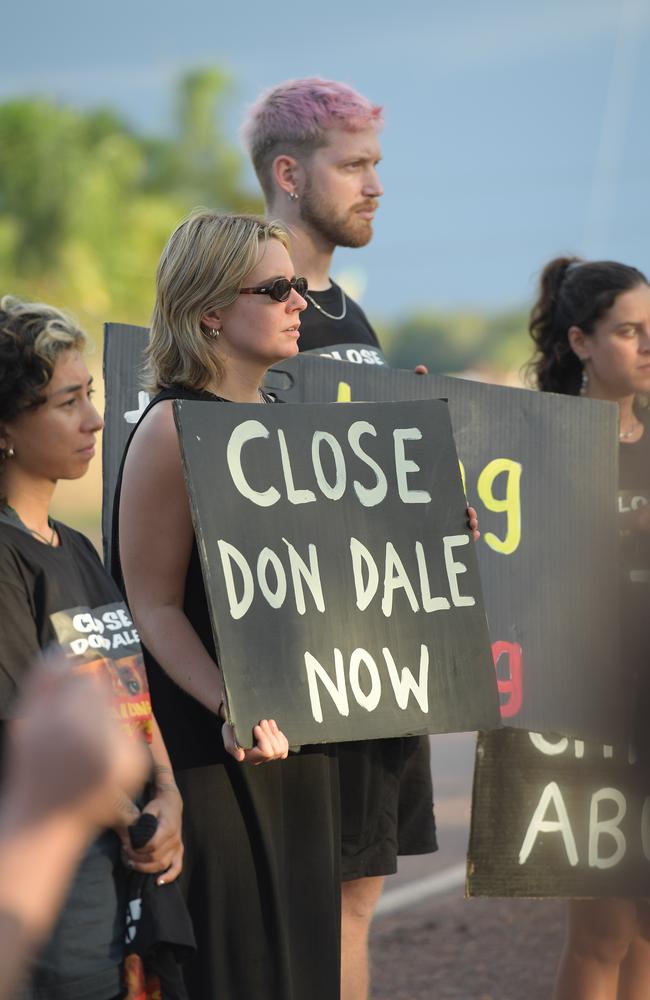

NT Children’s Commissioner Shahleena Musk reveals missed opportunities to help under 14s avoid prison

A Territory child was reported as the victim of abuse and harm 70 times before they ended up in the clink. See why the children’s watchdog believes we’re failing vulnerable kids.

Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A Northern Territory child was flagged to the authorities as being a suspected victim of child abuse, neglect, or maltreatment 70 times before they eventually ended up in the clink.

The Office of the Children’s Commissioner has found every child under 14 who was detained in the Territory had multiple notifications of alleged harm, signalling broken systems were missing opportunities to intervene before they became involved in the criminal justice system.

In a damning report, NT Children’s Commissioner Shahleena Musk concluded primary school aged children were being trapped in a failed system that inadequately addressed their needs as kids struggling with mental health or disabilities, victims of family violence or homelessness.

Ms Musk released the report just days before the CLP planned to revoke changes to the age of criminal responsibility, meaning 10 and 11 year olds can once again be jailed.

The OCC released its 49-page report on Friday, examining the stories of 17 kids under 14 who spent more than a week in detention, or had multiple stints in the cells.

It found 94 per cent of these children had been exposed to family violence, three-quarters had a mental health need or a cognitive disability, and half had multiple diagnosed disabilities.

The report found between the 17 children there were 456 child protection notifications warning of alleged harm of exploitation, which including child abuse or neglect, child maltreatment or harm.

One child was the subject of 70 allegations of harm.

It found of the substantiated harm investigations, 71 per cent of kids were victims of emotional abuse, 65 per cent of neglect and a further 18 per cent had been physically abused.

Despite all of the kids being “well known to multiple agencies and systems”, the OCC concluded their issues were not adequately addressed before incarceration.

“This results in fault being shifted to the children themselves rather than the agencies failure to address their needs from a young age as part of a co-ordinated service response,” it said.

“To put it simply, these are our most vulnerable children bearing the consequences of a failed system.”

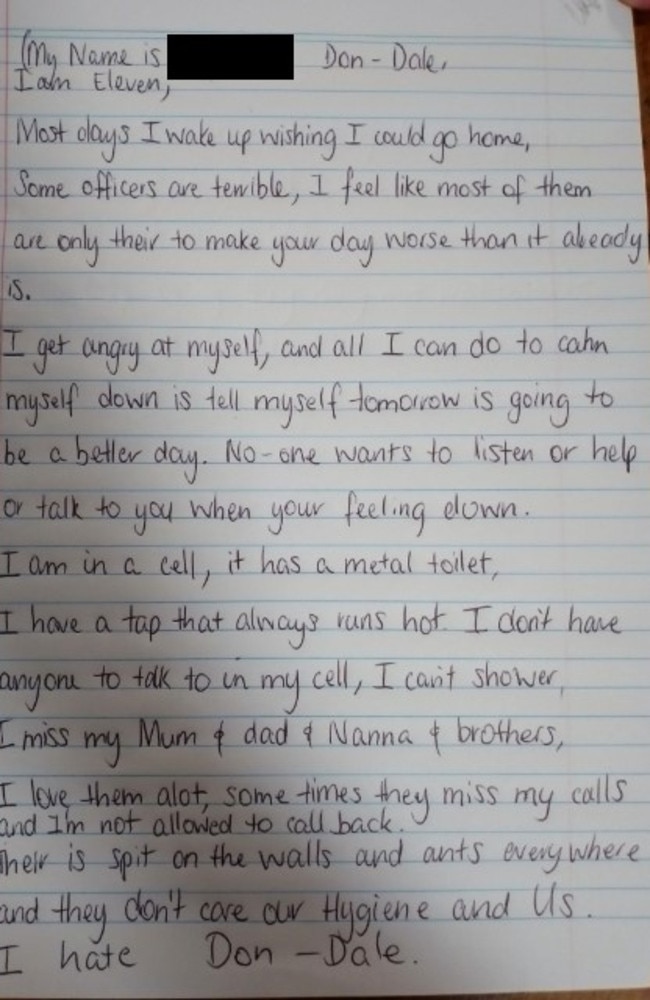

The OCC said many of the children told her they did not feel safe at home due to domestic and family violence and extreme poverty influenced their decisions to steal.

“For my family, ‘cause of DV, drinking, no where safe to go so you break into homes,” one child told the OCC.

“When I was little I was scared, I didn’t know what to think or what to do and it made me worry all the time. I got into trouble a lot because I was silly making bad decisions,” another said.

The report found poverty was a primary risk factor for involvement with the child protection system, with 74 per cent of children under youth justice supervision coming from the lowest socio-economic areas.

One kid told the OCC: “give the kids some money so they won’t have to steal”.

The report pointed to a critical intervention point in these children’s lives: the classroom.

It said there was a clear link between class attendance and imprisonment, with their teachers and principals well aware of the emerging red flags.

It found the “overwhelming majority” noted “extremely poor attendance” in Grade 6, while 76 per cent had reports about their behaviour in class.

Yet of those with in-school behavioural issues, only 65 per cent had education adjustment plans.

The report found the overwhelming bulk of research showed locking up children adversely impacted their health, wellbeing and future prospects, increasing their likelihood of a life “entrenched in the criminal justice system”.

“The criminalisation of young children with experiences of poverty, disability, poor health, low levels of education and exposure to harm is a legacy the NT can no longer perpetuate,” the OCC said.

“The earlier a child comes into contact with the criminal justice system, the greater the likelihood they will become enmeshed in that system and engage in chronic, long-term offending”

In 2022-23 the NT was locking up children 15 times the number of children compared to the national average, while also having the second longest average length of time under supervision in Australia at 218 days.

The report found 93 per cent of those in detention were on remand — unsentenced or waiting for their cases to resolve — and 94 per cent were Aboriginal.