NSW history: When ice began to be manufactured in Australia

Once a luxury only the rich could afford, blocks of ice used to be shipped to Australia from America — until we discovered a way to manufacture it on our own. Plus more NSW history.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Tartar had been travelling for more than four months from Boston when it arrived at Moore’s Wharf in Sydney on January 16, 1839. It was the middle of a hot Sydney summer and the people watching the arrival of the ship couldn’t have known what precious new cargo was on board.

When it left Boston, Tartar carried a 400-tonne block of ice harvested from a frozen New England lake, but when it arrived it weighed just 250 tonnes.

All the straw, peat and sawdust keeping the block insulated had been unable to stop a large quantity of it melting away.

Newspapers advertised the summer commodity at threepence a pound, a little more if you wanted it delivered to your home. But the truth was, from the earliest days, ice was a luxury only for the rich and businesses that needed it for food preservation.

It’s difficult to imagine in our modern world, where ice is simply the push of a button away, that not that long ago it was a rare and expensive commodity. And it sounds ludicrous that we had to import it from as far away as America’s east coast and Canada, or that the blocks would even last a four-month sea journey.

“It was a real luxury at first,” says City of Sydney historian Lisa Murray.

“But eventually the availability of ice had a trickle-down effect – and it’s not until ice is manufactured in Australia that it impacts daily life.

“At first, it’s used in shops to keep things cooler, particularly businesses like fish mongers. And once they figure out how to freeze rather than salt or cure food to preserve it, you have a tastier and more appealing product.”

On January 10, 1840, a second shipment arrived on board the Ceylon and the ice was all sold by mid-February.

Then, for some reason, the importation of ice into Sydney stopped and didn’t resume again until 1853 when the Monterey docked after 115 days at sea with 366 tonnes of ice.

It was still being advertised as late as October, which could mean that storage in dockside ice houses was improving.

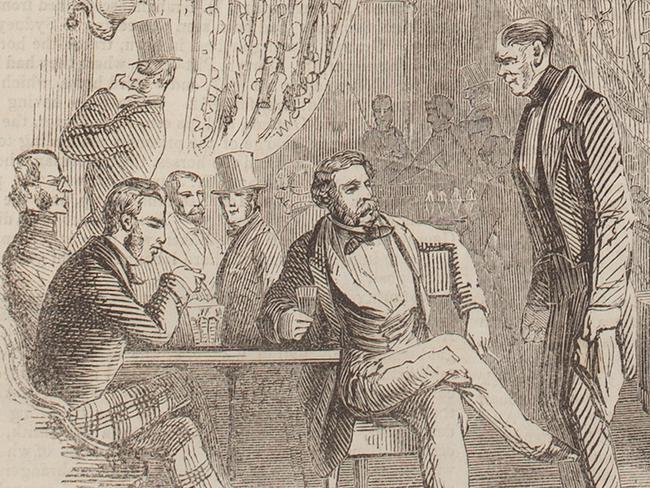

After the arrival of 353 tonnes of ice later that year on December 6, local cafes started promoting iced delicacies to their wealthy patrons, one newspaper hawking “iced sherry cobblers, iced brandy smashers, iced lemonade and iced soda water” for sale.

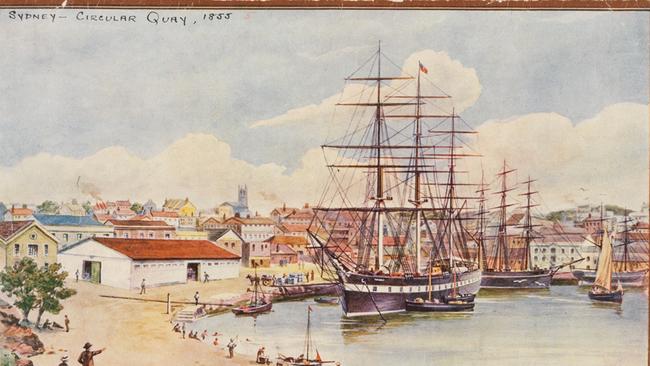

And when the Lowell docked at Circular Quay on January 12, 1855 with 491 tonnes of ice on board in the middle of a scorching Sydney heatwave, a new ice house was erected near the Quay.

By the following summer, John Poehlman – the proprietor of Cafe Francaise on George St who advertised iced sherry cobbler, ice cream, mint juleps and brandy smash – began selling ice commercially.

In an article for Dictionary of Sydney, historian Nigel Isaacs wrote that advances in refrigeration technology resulted in ice being manufactured in Melbourne in 1858 and blocks were shipped up the coast to Sydney.

Within two years, the Sydney Ice Company was established at Darlinghurst and they started making ice from Botany water.

Before ice was readily available, food was preserved using the techniques of salting, pickling and smoking. But with the manufacture of ice chests, people could keep food chilled in their own homes using large blocks of ice.

“It’s not until the post-World War II period that there’s a big expansion of electrical appliances and we start to see reliable, cheaper electrical refrigeration,” Murray says.

“Refrigeration is still considered a luxury item but it became more affordable in the late 1950s and 1960s.

“Older readers will remember the ‘iceman’ coming around to deliver large blocks of ice door to door.

“And what is also interesting is that once we have our own refrigeration and are able to also make ice, it does allow that opportunity to not only do things in the domestic market – like consume cold drinks and food – but to develop our exports, which leads to significant changes in our export markets.”

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

ARRIVAL OF THE ICE AGE

Before we had refrigeration to turn water into ice, we had to harvest ice from frozen ponds, streams and lakes.

New England entrepreneur Frederic Tudor is believed to have pioneered the ice trade in 1806 when he shipped large blocks of ice to the Caribbean island of Martinique.

By the 1840s, New England ice was being sent as far as England, India, South America, China and Australia. But it was closer to home where it had the biggest impact, revolutionising the US meat, fish, fruit and vegetable industries due to the ability to preserve food for exportation around the country and beyond.

FRIDGES COST MORE THAN A CAR

Before we had smart fridges with touchscreens and push-panel ice makers, people used a simple insulated wooden box called the ice chest to keep food cold.

An iceman would deliver large blocks of ice door-to-door to keep food chilled inside the ice chest.

The first mechanical fridge that didn’t rely on ice to chill items was released by Kelvinator in 1918 and cost almost twice as much as a Model T Ford car.

In 1923, Edward Hallstrom invented the first Australian-made refrigerator in his Dee Why backyard using kerosene as a power source. By 1964, it is estimated around 94 per cent of Australian homes had a fridge.

Unholy row over Sydney’s magical mystery train tours

They attracted up to 8000 people in a single day and proved wildly popular for young men and women in 1930s Sydney. But as quickly as they rose to popularity, the Palmers Mystery Hikes disappeared after just a few weeks.

The hikes were the brainwave of Government Railways, which collaborated with FJ Palmer & Sons department store to offer a range of train trips to unknown destinations on the outskirts of Sydney.

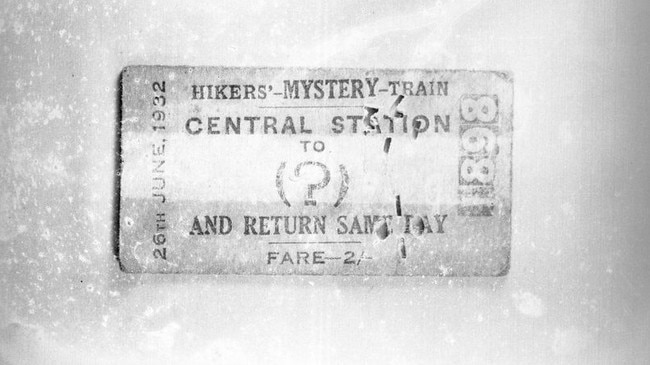

Much like the mystery flights that were popular in the 1990s, passengers would pay a sum – in this case two shillings, or about $10 in today’s money – and depart for an unknown destination where they would hike through the countryside and have a picnic.

There were five mystery hikes that took off from Central Station in Sydney in the winter of 1932, attracting thousands of young men and women; the ladies wore stockings and patent leather shoes and the men wore shirts, ties and hats, perhaps not the most appropriate attire for a Sunday rambling through the bush.

But with each passing week, the hikes grew in popularity.

The first hike on June 26 took passengers to Waterfall Station in Sydney’s south and then they hiked to Audley in the Royal National Park.

By the second hike on Sunday July 10, word had spread about the mystery tours and almost 3000 people arrived at Central Station armed with picnic baskets and walking sticks.

They were taken to Valley Heights at the foot of the Blue Mountains on four steam trains that left between 8.45am and 9am.

An overload of 200 passengers had to make do with the regular Blue Mountains train. The population of the tiny railway village of Valley Heights is said to have quadrupled in size that day.

Blue Mountains Historical Society vice president Robyne Ridge says the hikers made their way down the hill to Penrith after their hike, stopping to picnic along the way, before catching the homeward bound trains.

But few were prepared for the arduous task of walking through the Australian bush.

“Some had appropriate footwear,” she wrote in an article for the Blue Mountains Gazette.

“Others eventually went barefoot because of their sore feet. Some 500 of the party were treated by ambulance men for bruised and blistered feet.”

A few weeks later on Sunday July 24, a third mystery hike took participants from Central Station to Cowan Station in the city’s north on 12 trains where almost 8000 people hiked down to the Hawkesbury River.

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au

And on Sunday August 7, a trip to Stanwell Park near Wollongong south of Sydney was arranged.

While it may all sound like good old-fashioned fun, Ridge says the organisers of the hikes drew the attention of religious groups who thought the rambling escapes took the young people away from church on Sundays.

“This enjoyable activity raised the wrath of Rev WD Jackson at the Collins Street Baptist Church, Melbourne, who criticised the Railway Commissioner for fostering Sunday railway travel and ‘mystery hikes’ simply to make a ‘paltry profit’,” Ridge says.

A Mr Edgar spoke in the Legislative Council after just the first mystery hike claiming they “desecrated the Sabbath” and was quoted in the Canberra Times on July 8, 1932, saying it was “indecent for the railway to invite young people to take part in organised gatherings on Sundays. The railways were advertising Sunday trips to an unknown destination – in other words, perdition”.

But in a newspaper article dated August 25, 1932, the true value of these popular hikes were revealed. The article claimed that more than 50,000 hikers had participated in the trips, which garnered a profit of more than £3000.

The criticism didn’t just come from religious groups. In her book The Ways of the Bushwalker: On Foot in Australia, author Melissa J Harper says the trips were slammed by “serious bushmen” as “senseless stunts”.

All the opposition could be the reason why the mystery hikes died out as suddenly as they had started.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

THE FIRST MYSTERY HIKES

The Sydney hikes could have come off the back of the first London event, which was held just a few months earlier on March 23, 1932, and had proved extremely popular.

London’s very first Hikers Mystery Train Express took adventurous passengers from Paddington Station in London to locations such as Oxfordshire and Berkshire on four packed carriages for four shillings each and it was said even the conductor had no idea where the train was going.

A little better organised than the Sydney events, the London hikers were given a map of the proposed route once on board the train and offered a meal to enjoy along the way to their destination.

SHOPPING AT FJ PALMER & SONS

A newspaper advertisement for the menswear retailers in 1910 promoted the wide range of products they sold.

They carried new suits, shirts, socks, braces, collars, handkerchiefs – “in fact everything new” – but most notably was their claim to sell “new underwear of the thinnest kind”.

The retailer started around 1880 in a modest little shop in Haymarket but by the pre-WWI years were big enough to require new premises on the corner of Pitt and Park streets.

At one point, they even had legendary cricketer Donald Bradman promoting their wares.

Inside Sydney’s first jail at The Rocks

To check in at the Four Seasons Hotel in Sydney is a treat that affords some of the city’s best harbour views from its trademark corner suite windows – a world away from the experience that awaited arrivals at the very same location 225 years earlier.

The five-star hotel, one of the first luxury hotels built in Sydney when it went up in 1982, stands on the location once occupied by Sydney’s first jail.

An excavation of the site in 1979 by Patricia E. Burritt on behalf of the Heritage Council of NSW – undertaken to locate and record any evidence relating to the jail before the hotel complex was given the green light – recovered silver and bronze coins, including a 1799 bronze George III farthing, clay pipes, a stoneware jug, earthenware shards and a white porcelain dish.

But it was a heavily-corroded leg iron dating to the early days of the colony that confirmed the site of the old Sydney Gaol.

“None of the prisoners in the crowded conditions of the old Sydney Gaol on George St could have ever imagined that the piece of real estate they were occupying would one day be the site of a luxury hotel,” State Library of NSW librarian Rachel Franks says.

“We would never think of putting a prison in the middle of The Rocks today, but back in the early 19th century it made perfect sense. There was already a history of crime and punishment in the area.

“The first man judicially hanged in NSW, Thomas Barrett, was hanged on February 27, 1788 for stealing food very close to where the jail was built.

“The hanging site was about halfway between the men’s and women’s camps that had been set up just after the arrival of the First Fleet.”

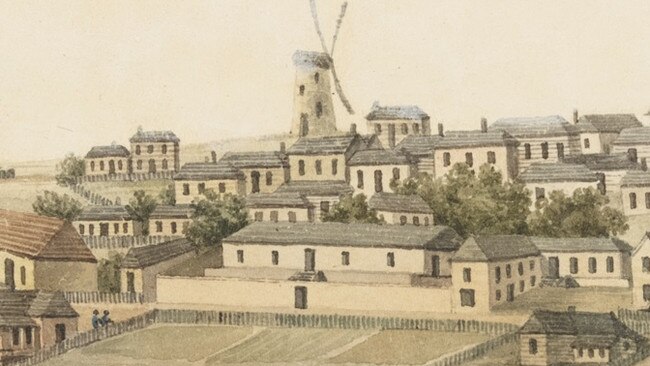

Initially criminals were detained in part of the colony’s storehouses and in tents but in 1796 Governor John Hunter ordered the construction of two gaols, one in Sydney and the other in Parramatta.

They were to be built using materials provided by free settlers — 10 logs each, double for larger land holders.

The Sydney building was completed in June 1797 and comprised a main log building 25m- long and divided into 22 cells with a thatched roof and a wooden floor coated in clay.

It also provided a brick debtors building, which would keep these prisoners away from other criminals, and was enclosed in a high fence.

Less than two years later, in February 1799, it burned to the ground and four months later a new stone building was begun at a cost of almost £4000.

The new structure followed an army barracks-style plan and had six cells for condemned prisoners as well as staffrooms, offices, storerooms, a cookhouse, and separate cells for debtors, disorderlies and females.

Outside the western wall, between present-day Gloucester and Harrington streets, was the gallows or “Hangman’s Hill” which was easily visible to the passing public.

Attending a hanging was an acceptable form of entertainment with local papers often saying women and children present in the crowd and who often got more of a show than they bargained for.

The September 26, 1803, hanging of Joseph Samuels didn’t take place at the old Sydney Gaol, rather closer to Central Station at the Brickfield Hill Gallows. Samuels had been found guilty of a theft which led to the killing of Constable Joseph Luker, who went down in history as the first Australian police officer killed in the line of duty.

On the day of Samuel’s hanging, the executioner made three attempts to complete the task but failed due to the rope breaking twice and finally unravelling.

Public outcry led to a last-minute reprieve for Samuels who was saved from the hangman’s noose.

By 1835 the old Sydney Gaol was dilapidated and overcrowded and plans were made for a new, bigger jail to be built at Darlinghurst.

On June 7, 1841 the prisoners were chained together and walked in a procession up George St to Darlinghurst Gaol, the female felons veiled and dressed in black at the rear.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

TWO CENTURIES OF PUNISHMENT

At the same time that the old Sydney Gaol was being built in 1796, a similar one was built on the banks of the Parramatta River.

And like its Sydney counterpart, it too burned down in 1799. A second jail was built in 1804, but three years later it was also damaged by fire and plans were made for a new, grander jail on the corner of Clifford and Dunlop streets near the Female Factory, which would ultimately cost almost £35,000.

It opened on January 15, 1842, and until it closed in 2011, it was Australia’s oldest serving jail.

JAIL BOSS’S FAMILY LEGACY

Henry Kable was charged with burglary in March 1783 in Norfolk, England, and sentenced to transportation to America, but the American Revolution meant he was sent instead to NSW, arriving on the First Fleet’s Friendship with his partner, convict Susannah Holmes, and their baby, Henry.

Governor Phillip appointed him an overseer shortly after arriving and in 1797, as chief constable of the new jail. But he was dismissed in 1802 for his illegal involvement in pig trading.

Today, there are more than 100 descendants of Henry and Susannah, who had 11 children together.

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as NSW history: When ice began to be manufactured in Australia