Vincent Lingiari’s vision left to rot and die

FIFTY years after Vincent Lingiari led 200 people off Wave Hill Station, what has become of Daguragu and the elders’ dreams for their descendants? Zach Hope reports

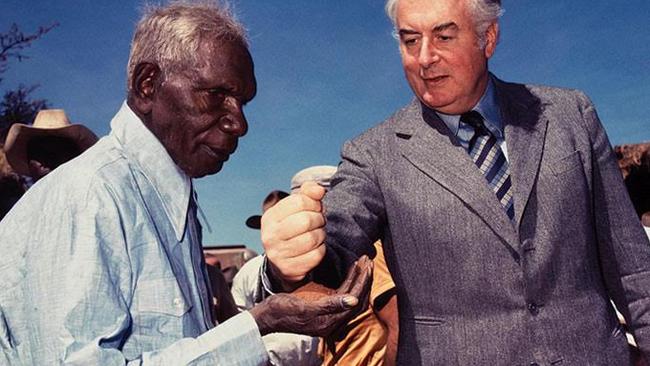

IT is the cradle of land rights, the home of the ‘Walk Off mob’, where Gough Whitlam poured red sand into the cupped hands of Vincent Lingiari to usher in a new age of Aboriginal self-determination.

There is supposed to be a cattle station here and orbiting economy with shops, jobs, a clinic and a school teaching Western and Gurindji ways.

Descendants of the land rights heroes of 1966 are supposed to be working their land independent of the white system. More than equal wages and conditions, this was Lingiari’s idyll.

Today, Daguragu — the dream of Vincent Lingiari — is starved, beat up and dying. Donkeys make homes in abandoned buildings of industry. People make homes in the dilapidated buildings of government.

The community has borne half a century of government duplicity and over promising; bad local management and corporate naivety; land tenure bureaucracy and coercion.

The cattle industry modernised. Grog arrived.

Besides the Daguragu creche and successful ranger program, most of what’s left of the vision has been subsumed by Kalkaringi, the former government-established Wave Hill Welfare Settlement 8km away, described by elders of the Walk Off as rubbish country.

Kalkaringi is no utopia, but in relative terms it is thriving. Here are the services, school and even a social club selling mid-strength beer three hours a day. It is here thousands camp this weekend for the Freedom Festival to mark 50 years since Lingiari led 200 brave men, women and children off the oppressive Wave Hill Station in search of a better life on their traditional lands.

A complex tension between traditional owner groups of the two communities has grown with Daguragu’s marginalisation.

The Walk Off sowed land rights across Australia. But what have the Gurindji and related tribes of the region reaped? Is the Freedom Festival a celebration, commemoration or a wakeup call?

SELMA Smiler, Lingiari’s great-granddaughter, calls the old man her “inspiration everyday”. She says the Walk Off is a source of pride for everyone in Daguragu and Kalkaringi, but: “Me, I feel sad because (Daguragu) is where my great grandfather wanted to settle.”

Lingiari’s grandson, Sonny Smiler says: “He wouldn’t be happy. There’s no employment around Daguragu.”

Author Charlie Ward, who will launch his book A Handful of Sand this weekend, believes the 50th anniversary is an opportunity to ask difficult questions.

“I think the bravery, the guts to take that action to walk into the unknown still inspires thousands, and so it should — it’s standing up to a power against oppression,” he says.

“How would the leaders look at the situation today?

“We can obviously do better and go further. These are the conversations that need to be had with government and other players.”

The betrayal of Lingiari’s Daguragu dream began early.

Kalkaringi, 800km south of Darwin, was known as the Wave Hill Welfare Settlement.

It was little more than a police station and a few dongas on Crown land when the Walk Off mob (as they are nicknamed) swapped the banks of the Victoria River for Wattie Creek, later to be known as Daguragu.

Sandy Moray, or Tipujurn, the elder who encouraged and inspired the younger Lingiari and leaders to take a stand, was the traditional Daguragu owner.

But under Australian law, Wattie Creek was pastoralists’ land.

John Gorton, the second of six Prime Ministers to feature in the Gurindji struggle for land rights, ignored them at first, then in 1968 pledged 20 homes, not for Daguragu but Kalkaringi.

“There are references of people just wanting to take the air out of this support that was building around the Gurindji,” Ward says.

“It was a way of circumventing issues of possible Aboriginal claims to title.

“If it was Wave Hill Station it could therefore be Newcastle Waters, Helen Springs, the whole country.

“But the (Gurindji) stance was they intended to create their lives and their future at Daguragu, and have an independent community, whether there was support or not.”

The homes were rejected by the elders, but set Kalkaringi on a new course. Despite the Gurindji wishes, and despite inferior land and water access, it became the community of choice.

Initially this was a political strategy to water down Gurindji ambitions for pastoralist land, Ward says, but over time it became a matter of underlying land tenure.

The elders watched more and more services move to the Crown land of Kalkaringi.

“It gets its own momentum and then it becomes a case of ‘well, how can we take out all the resources and infrastructure that we put in and shift it somewhere else?’” Ward says.

“The school going to Kalkaringi was a massive sore point for the elders for 15 years.

“They said repeatedly that integral to their vision was to educate their kids and have input — to have primarily mainstream education — but it was essential to the elders that happened at Daguragu.”

Ministers and managers came and went. Agreements were broken or fell short.

Governments and pastoralists feared the precedents to be set by any act of conciliation or compromise.

After self-government in 1978, the Territory parliament became another layer of belligerence and bureaucracy upon compounding frustration, Ward says.

Internally, equal pay in 1968 opened up the communities to cars and the nearest takeaway alcohol at Top Springs. People became alcoholics. They died in car crashes. There was violence. The younger generation found interests other than cattle.

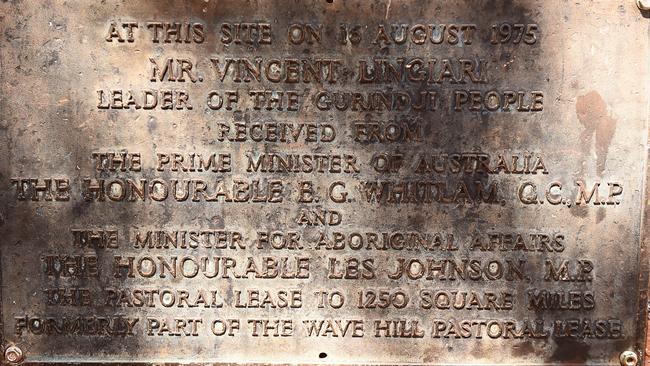

In 1975, Whitlam visited Daguragu. A plaque stands where he scooped the sand to pour into Lingiari’s hands.

Whitlam gave the Gurindji a lease that day, not the underlying tenure for which they and activists had campaigned. There was celebration nonetheless because it meant the Gurindji could pursue their cattle station in earnest. Likewise, the government could build Daguragu.

And, in any case, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, and the proper deeds to the country, was supposedly imminent.

The Gurindji were to be disappointed again when Whitlam was dismissed months later. While Malcolm Fraser passed a version of ALRA in 1976, it wasn’t until 1986 the Gurindji won ownership through a drawn-out lands claim process.

Long before this, despite generous federal government and union subsidies, the cattle station, Muramulla, had begun to disintegrate.

The old stockmen were never taught the financial or managerial side of things, Ward says, and the business had only become more complex since they knew it in 1966.

The final blow was the Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign of 1979.

While only one or two Muramulla cows tested positive, Ward says, half the herd was slaughtered because the Gurindji could not meet all the necessary conditions such as appropriate fencing and monitoring.

Muramulla went bust in the late 1980s. The associated shop had been pilfered and mismanaged to death by 1982. The Vincent Bakery flooded in 2001 and was never restored.

In 2007 The Northern Territory Emergency Response put controls on citizens, while equipment and jobs were lost the following year when the Daguragu community council was dissolved in Territory Labor’s controversial super shires initiative.

Today the Gurindji have their land, but any meaningful economic activity is at Kalkaringi.

The CLC can only point to two recent projects at Daguragu: upgrades to the football oval and the basketball court, using $300,000 from compensation money for compulsory land acquisition during the Intervention.

Sandy Moray’s grandson and Daguragu traditional owner Roger King confused the otherwise gleeful crowd at yesterday’s Freedom Festival opening when he told them the ceremony should be by Wattie Creek instead.

“When Daguragu went down and Kalkaringi went up, my grandfather not happy about that. He think my country been rubbished. No respect,” he told the NT News later.

“Me and my family feel really sad about that. We don’t even know who to talk to.”

Referring to the 2008 council dissolution, younger man John Leemans says: “Everyone has been unemployed since they took the assets away.”

Traditional owners of Kalkaringi formed the Gurindji Aboriginal Corporation in 2014 following a successful native title claim over the township.

Underlying tenure remains with the government, but the traditional owners have power to negotiate. They recently agreed on a subdivision creating close to 20 new housing and commercial lots.

In addition, Kalkaringi will receive four homes and one upgrade promised for the final two years of the National Partnership on Remote Indigenous Housing. It is one of the few places in the Territory where builders can move in immediately and get to work.

At Daguragu, the traditional owners must sign the community back to the Federal Government in the form of a 40- or 99-year lease to get its ‘promised’ four homes and two upgrades. Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion has made clear homes are conditional on these leases, while traditional owners from across the Territory have made clear they don’t want to sign their communities away.

Such conditions don’t apply to other items of government infrastructure in townships: police stations, court houses, runways, schools and health clinics. Homes are the government’s choice of carrot.

In terms of business, Daguragu and Kalkaringi form a microcosm of what long-time Aboriginal affairs bureaucrat Bob Beadman calls “the land rights divide”.

“(ALRA) has kept Aboriginal land intact so it hasn’t been whittled down by tricky mortgagees and so on,” he says.

“On the other hand, it’s also been an effective barrier to business migration of many, many kinds; whether it’s been a service station or tyre replacement or women’s hairdressing salon.”

In this way, the rights inspired by the Walk Off mob are suffocating the very place they were born.

CLC director David Ross and Northern Land Council chief executive Joe Morrison reject this notion.

Ross calls such language “CLP mythology … used as a convenient excuse for government failures over many years to invest in infrastructure, education and training in the bush”.

Scullion’s rationale for township leases is simple enough: free enterprise must drive economic growth and commercial banks are unlikely to lend against assets they cannot repossess — such as Aboriginal land. Further, if banks were willing to loan, people in remote communities could participate in the Australian dream of home ownership.

He has successfully negotiated leases over Wurrumiyanga, Milikapiti and Wurankuwu on the Tiwi Islands, and Angurugu, Umbakumba and Milyakburra on the Groote Eylandt Archipelago.

Yet his office can only point to one business — a supermarket — established with help from a commercial bank loan.

There are 15 homes loans in these communities, but all are through Indigenous Business Australia, which assists only if would-be homeowners don’t qualify with commercial banks. Beyond rules, regulations, policy and tenure, there is another problem at Daguragu, Beadman says.

“The last time I asked questions down there — ‘what are you mob doing as an enterprise base for yourself, utilising the land that you got hold of?’ — they had their land given over on agistment and they all continued to live on welfare benefits,” he says.

Traditional owners from Daguragu and Kalkaringi met last week to discuss their grievances. The NT News has been told it ended in agreements to work together to pull off the Freedom Festival, the most important community event since 1986.

Meanwhile, at yesterday’s congratulatory opening address by Warren Snowdon, the Parliamentary member of the seat bearing Lingiari’s name, backs were slapped and the whitefella campers clapped like evangelists.