Tech entrepreneur James Dack’s journey from homeless man to millionaire

His rags-to-riches story has taken him from Woolloomooloo housing commission to a Woollahra mansion, but businessman James Dack still tackles his private battles with his fists.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Waltzing past his luxury Mercedes-Benz, James Dack says: “This car, the $20 million Woollahra house, doesn’t mean a thing when you step through those doors.”

The multi-millionaire businessman climbs the stairs of Woolloomooloo PCYC, wraps his hands, pulls on the gloves, and does 12 rounds of boxing with Sydney Roosters under-20s conditioning coach Steve Driscoll.

“It’s cheaper than therapy,” Dack says, the sweat drenching his plain black T-shirt.

Given his tumultuous upbringing, the 59-year-old could easily be spending a good portion of his fortune lying on a shrink’s couch.

Instead, Dack prefers to be standing. Moving. Punching.

Before the Merc and mansion, Dack lived right here, in the change room of this PCYC building, with his late brother Stephen.

“Whoever got back first in the evening got the bed, the other one had to take the couch,” he says, pointing out where the small microwave and fridge once stood in this tiny space; when in his early 20s he had no other place to call home.

These days, home is the sprawling eastern suburbs estate with wife Mary — daughter of Jack Cowin, owner of Hungry Jack’s with an estimated worth of $4.5 billion — and their children Riley, 14, and Emily, 13.

Dack first encountered Mary Cowin at a party when both were in relationships.

“Then we met two years later, we were coming out of relationships, the chemistry was too strong to ignore,” he says.

But even after establishing himself as one of the most successful real estate agents in the country’s history, Dack still fights a private psychological battle 20 years into his marriage.

“You want to be the man of the house,” Dack says.

“I’ve been successful in my own right, but when you’re talking about a father-in-law worth $4.5 billion, the pressure comes from measuring yourself against that.

“My wife looks up to him, so there’s a natural anxiety as to whether you measure up, particularly when this bloke is not only a huge success in business but has raised four wonderful children and is a great guy.

“All those things are inside my head.

“But I am so grateful, because they are a great family — we only have their side of the family … I give a lot of credit to my mother-in-law Sharon, she holds our family together.

“I’m like most people, I will swear when I talk, especially when I’m being expressive about something I’m passionate about or interested in.

“But I’ve been careful to never utter a swear word in front of her.

“And in 22 years, I’m proud to say I haven’t.”

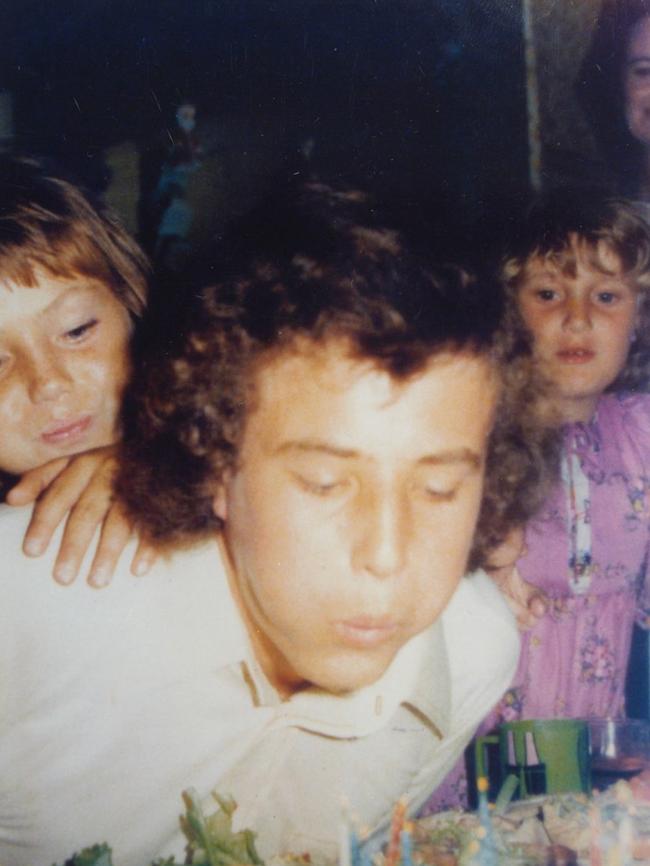

FROM BOY TO MAN OF THE HOUSE

Manners wasn’t a strength for Dack as a child when he lived in housing commission in Woolloomooloo, surrounded by drunks, drug addicts and prostitutes.

Aged 15, he physically threw his alcoholic, abusive father out of the house to protect his mother Florence, and younger siblings Stephen and Alison.

“That was the seminal moment,” Dack says.

“My mother was ill a lot, and his behaviour caused a lot of that.

“That day, I was old enough and capable enough to do something. This person was not representing anything that I had admiration for.”

From there he went from boy to man of the house.

But Dack still carried guilt from the day, aged 12, he tried to break into a perfume factory and electrocuted himself on a live wire, spending two months in hospital receiving skin grafts.

“I was about to sit an exam for a scholarship to a private school. I was top of my class in every subject, but when I got out of hospital I wasn’t the same person,” Dack says.

“I couldn’t grasp concepts and learn as quickly as I’d been able to. The scholarship opportunity disappeared.

“I don’t know how, but my mother still managed to put us through private school education.

“Every week I think about how she did it. I’m astonished. My resilience comes from her.”

Florence succumbed to cancer aged 52.

Dack recalls waiting for his mother to finish her overnight cleaning shifts. Around 4am, her footsteps would cast a shadow in front of the door to their flat.

The teenager would welcome her in, share a muffin, and listen to stories of how stock exchange traders would deliberately throw rubbish on the ground for her to pick up.

At 17, he took up a job of his own to provide support, at St Vincent’s Hospital as a porter, taking patients from one wing of the facility to another.

The boss of operations at St Vincent’s, John Ireland, had heard Dack’s name ring out.

“His bosses told me he was turning up late, having days off, they weren’t impressed, they told me he had to go,” Ireland says.

As fate would have it, the lanky teenager was hooning down a corridor on an empty rolling bed one evening when he nearly ran over Ireland, who was waiting for the elevator.

“Come to my office tomorrow,” Ireland told Dack.

That night, Dack was convinced he’d be sacked, but was spurred on to attend the meeting based on his mother’s advice: “Always turn up, don’t run from responsibility.”

“So he turns up and I ask him why he has been coming to work late,” Ireland recalls.

“And he tells me that his mother has cancer, he has two younger siblings, so the days he’s late he’s packing lunch for them, and the days he doesn’t turn up are when his mum is having a difficult day and he’s in hospital with her.

“He had his HSC going on, and he said to me, ‘Life is an oyster, and I’ve got a baddie, I’ve got no chance’.

“So I gave him one.”

Ireland gave Dack a clerical role in the hospital’s pay office.

Quickly, the intuitive youngster rose to run the entire section, before the Department of Health poached him.

But the hits would keep coming.

A NEW LIFE

In 2007, the untimely death of Dack’s champion boxer and advocate lawyer brother shook him to his core.

A few years into his health job, Dack made the switch to real estate with John McGrath, and the pair raked in millions buying and selling houses for prime ministers, media moguls and hedge fund magnates to form the dominant business of the era.

But in 2014, Dack stunningly quit the industry, seeking a more self-fulfilling existence; burning his business suits in a symbolic cremation of the life left behind.

Many doubted whether he’d go anywhere with his new firm, Sunshine Group Investments.

Not American entrepreneur Michael Jennings though, who was overwhelmed by Dack’s grit and determination, after the latter sunk six figures into his business, as the market turned sour and others began to bail.

“James was one of our early investors, he saw the vision I had and really believed in it,” says Jennings, founder and chief executive of Next Green Wave, a company that distributes “craft artisanal cannabis products” throughout California.

Turbulence hit last March.

“Our share price dropped to US3.5c, a lot of shareholders, particularly ones that had come in from Australia with James, were pissed off with me,” Jennings says.

“A lot of them were jumping ship.

“But James was always supportive, that was a testament to his character. Even as successful as he is and his family is, he’s just very grounded and when he supports you he will do so not just financially but as a friend.

“What I had been preaching, and what James was believing, was that if we had enough runway we could get off the ground, because our conversion rate from revenue to profit is unparalleled.”

Their faith is paying off, with NGW now worth $US130 million from its low of $US10 million in market capital last March.

Jennings is now open to exploring a craft cannabis business in Sydney, subject to the drug being legalised for commercial sale, while Dack is banking on turning his millions into more as the company grows.

But his ambition doesn’t stop there, with Dack adamant his next focus had to benefit humanity, not just his own bank account.

Chairman Frank Poullas told Dack he was “the missing piece of puzzle” in Magnis Energy Technologies Ltd, a company with a mine full of graphite in Tanzania — graphite being the best non-metal conductor of electricity.

At the same time, Magnis purchased a lithium-ion battery production facility in New York, with the prospect of clean-energy batteries that don’t require fossil fuels to power factories around the world propelling Nobel Prize-winning chemist M. Stanley Whittingham to join the board.

“I’m a kid from housing commission in Woolloomooloo, being offered the chance to become executive director of a company with a Nobel Prize winner on its board, it’s staggering,” Dack smiles.

“It’s clean energy, which is vitally important to the planet, and so I felt for the first time since I left real estate, I had a project worth investing my time and effort in.”

When Dack took the role — that offered him a $380,000 sign-on fee, an annual salary of $300,000, and 20 million shares in Magnis, each worth 7c on the share market with the company only having $200,000 in the bank — he was tasked with raising up to $50 million in capital.

This week, Magnis, up to 33c a share, called a trading halt with an announcement expected next week.

Dack’s 20 million shares have increased astronomically, but he refuses to get into specific figures regarding his latest windfall.

“I find that when people start talking about their income or their position, nine times out of 10 there’s something missing in them,” Dack says.

“To try to justify themselves to the company they’re in with big numbers, that is not the essence of them. It is a by-product of what you do, but it’s not all you are.”

This is why Dack has remained actively involved in the NSW PCYC as a director, a donor, and a mentor.

CLEAR AND PRESENT

“If I can help someone avoid what I had to go through during my childhood, I must,” Dack says.

“This place gave me shelter when I needed. I feel its pulse.”

Dack hasn’t touched alcohol in two years, wanting a clear head at 6am when he jumps into his pool for laps, ahead of his daily boxing sessions.

“I’ve seen a lot of people buckle, I don’t want to do that,” Dack explains.

Driscoll, holding the pads that thud with combinations, calls for more effort in the 12th and final round, as Dack’s body begins to waiver, but not fail.

“I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees,” Dack says.

Later, at his regular lunch spot in Darlinghurst, Bill and Toni’s, where a picture of Stephen Dack’s state boxing victory hangs behind the counter, Dack is closely scrutinising an email offer on his phone that could turn the fortunes of Magnis.

He can’t say much.

“I just wish my mother was here to see this,” he says with a grin.

“To see how it all unfolded.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Tech entrepreneur James Dack’s journey from homeless man to millionaire