Systemic and cultural failings to blame for war crimes

War brings out the best and worst in people. But the failing – in the systems and culture – allowed them to go to the worst place, says former commando.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

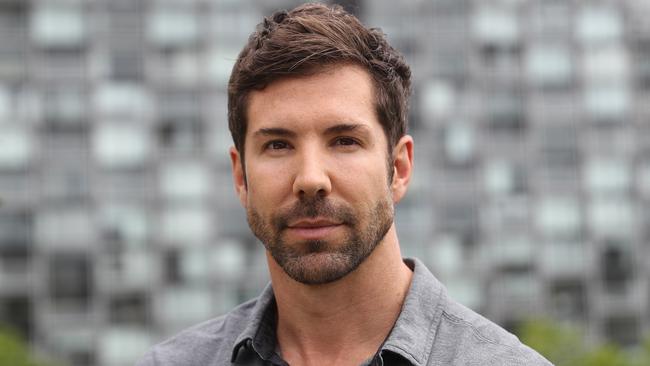

HESTON Russell spent 16 years in the miliary, reaching the ranks of Special Forces Commando Officer. He served in Timor Leste, Afghanistan and Iraq. He twice gave evidence to the Brereton Inquiry.

This is his response to the inquiry.

AM I disappointed with the Brereton report? extremely, yes.

My only hope is this Office of the Special Investigator (which is yet to be announced) will look into how it came to this.

We need to understand the full context behind how these incidents occurred. At the moment, as I see it, it’s an inquiry into a conventional force which was told to go over that hill and attack that enemy and ended up going rogue.

It’s not an inquiry into a Special Forces element that was failed or wasn’t given clear parameters on the mission they had.

What we had to do to support alliances and put ourselves at risk to maintain the situation over there, you don’t read about.

There were no other fighting forces in Afghanistan taking the fight to the enemy. There were so many jobs.

I lost my soldier Corporal Scott Smith doing a three-day clearance with tanks in Helmand Province, the first time Australians have fought with tanks since the Battle of Binh Ba in Vietnam.

You don’t read that anywhere but he died manoeuvring with a tank – that is not Special Forces but that was the job we were asked to do and we did it.

We were literally in the commanders’ reports assessed by the kill counts and … the Australian public measured the conflict by the number of Australian dead.

We had a mindset of the conflict at looking at deaths – not why we are there – and at the end of it wondering why something went wrong.

I’m not saying individual actions are excusable, I now just really want this process to fully investigate the context that allowed (these incidents to occur).

Like all Special Forces, we are held in this high esteem as the most elite.

You start breathing and breeding into that.

Those expectations are placed on you. Every single politician, general, and person that came to visit always wanted to go in and see the Special Forces guys and commend them.

They also wanted to look at the kill counts and the tally boards.

We were killing foreign fighters coming in from other countries into Afghanistan, all this ‘good shit’.

That is all they cared about not how it was done, they just wanted the results.

War brought out the absolute best in some of the most magnificent people I’ve ever seen. But being exposed to war, operating in this environments, will obviously potentially bring out the worst in people and it did that.

The failing – in the systems and culture – allowed them to go to the worst place instead of the best place.

I gave evidence twice to the Brereton inquiry.

They focused on my individual missions and tactical actions on the ground.

I was never questioned on culture. I was never questioned on any of this competitive unit stuff.

I was always kept in my lane and this is probably part of where there’s actually issues with the inquiry. The people that were asked about this were those senior commanders who are a by product of leadership from the top and then the bottom up and to every layer.

I was crucified in my conversations with General Brereton and the other colonels in my evidence, it was not an enjoyable process.

They went into details that made me question all these actions.

I made a couple of tactical decisions that in context I want the Australian public to understand.

I authorised my guys to fire warning shots because I was sick of us shooting people who were dropping weapons and running away to another weapon or dropping weapons and running to another position, out of the rules of armed conflict.

Because they knew our rules of engagement, I was sick of shooting at people who were talking on radios directing people to where we were so their friend could arm IEDs – because we were listening in to them.

So I authorised my guys to fire warning shots because we could not catch the people and we were legally authorised to shoot them.

But basically that was a breach because Australians are not authorised to fire warning shots.

I actually saved more Afghan lives than killed them, as I would legally have been authorised to.

Gen Brereton and his team basically used that, my permitting my guys to do that, to unpick the entire legitimacy of my moral and ethical leadership and actions in combat.

I don’t think the report besmirches the name of our regiment or the SAS.

The actions of a few in the context of the thousands we sent over there, over that 10-year period, has to be remembered.

The people the government asked us to partner with and all these stories we had to keep quiet, then all of a sudden individual actions are brought before inquiries.

Our strategy, our policy and our outcomes in Afghanistan for the Special Forces contingent were always branded as being in line with Australians mentoring and support for the return of power to the people of Afghanistan.

But we were actually there conducting targeting operations.

This has to be made known.

We were measured on kill counts, we were measured on how many bad people we killed.

The nature in which the SASR guys conducted their operations – their tactical commanders, their officers, their troop commanders, their captains – were back at the operations room watching the operation on ISR (drones) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle assets.

That is a huge critical difference. If they were with their men they would have seen (the bad elements).

Command responsibility doesn’t end because you are not there on the ground.

You delegate your authority for your guys to go and conduct tasks.

Its not abdication, you are still responsible for their actions.

* Edited extract from a recorded interview with Charles Miranda

For those needing support:

· The Defence all-hours Support Line is a confidential telephone and online service for ADF members and their families 1800 628 036

· Open Arms provides 24-hour free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families 1800 011 046, or through SafeZone on 1800 142 072.

MORE NEWS

The year the Army became a national disgrace

Army chief: ‘Why did this happen?’

Shock war crimes report: What happens next

3000 soldiers could lose medals

Actions of few endangering others

Five words Australia’s military must use right now

War hero’s army squadron disbanded

‘Lies told’: Defence Force chief’s speech stuns

Originally published as Systemic and cultural failings to blame for war crimes