How police finally caught up with notorious rapist and killer Mr Stinky

TWO bodies in the bush. A rapist terrorising the young mothers of Donvale. And the clue kept secret for 16 years that finally led to the man responsible for all of it.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN a cowshed at Ardmona, west of Shepparton, a young sharefarmer’s wife called Lesley turns on the old shed radio for the 6am news.

She starts milking the cows waiting in the yard.

The Righteous Brothers’ Unchained Melody blares out and Lesley feels bad.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST iTunes | RSS

MR STINKY: HOW A MONSTER WAS MADE

COMANCHERO: INSIDE AUSTRALIA’S BADDEST BIKIE GANG

She is trapped by the moody lout who got her pregnant on her 16th birthday and treats her badly. He has been out all night again.

He’s not even home in time to start milking.

She has two toddlers shut in the spooky old weatherboard house across the yard, is pregnant with a third. The Gawnes, who own the farm, sense her plight but she never complains. She is 19.

As she puts the suction cups on swollen udders, she hears the local news. One item catches her attention: two Shepparton teenagers have gone missing overnight. Car found. Police baffled.

Lesley feels uneasy. Unease changes to anger when her husband steps silently into the shed and starts work.

The missing teenagers

AT first, everyone wants to believe the missing pair are just love-struck runaways.

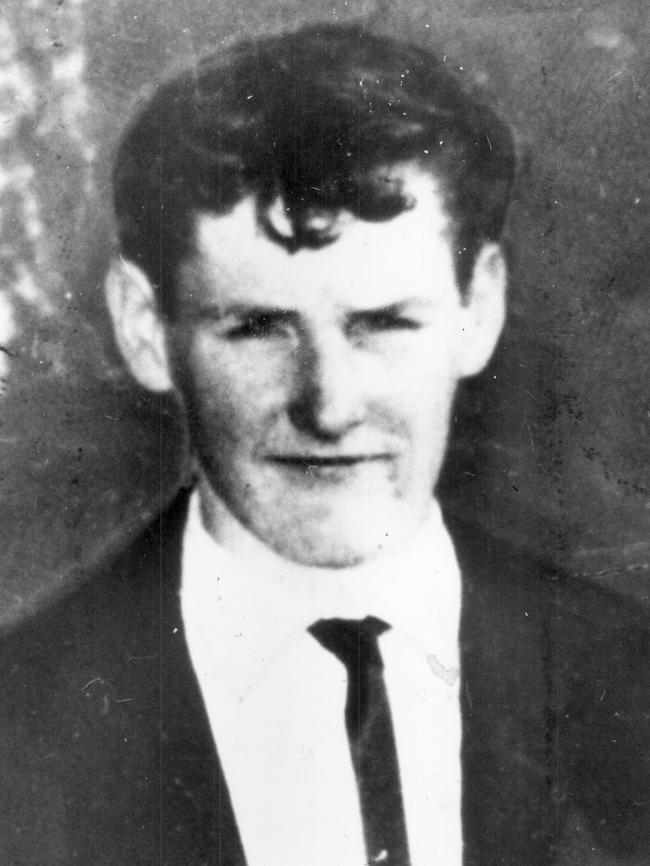

He is Garry Heywood, 18, an apprentice at his family’s Shepparton panel works.

She’s Abina Madill, 16-year-old farmer’s daughter, recently employed in the office at Heywoods’.

Garry is popular and has an immaculately restored FJ Holden.

Abina has a boyfriend, apprentice mechanic Ian Urquhart, but on the Thursday evening of February 10, 1966, he has to work late so can’t take her to the big “mod” concert at Shepparton Civic Centre that night.

That random thing is the difference between life and death for Abina.

Because Urquhart can’t get to the concert until late, Abina and a friend agree to meet Heywood and his mates at Star Bowling Alley.

They later return to the concert with the boys. Roland Storm and Yvonne Barrett and other big acts are playing.

When Heywood suggests going for a drive, Abina agrees because her boyfriend hasn’t arrived yet. When Urquhart turns up and hears that Abina is out cruising in Heywood’s hot Holden, he’s furious.

“I’ll kill the bastard. I’ll belt him,” he swears.

Any adolescent might have said the same but those few heated words wreck his life.

When Abina and Garry don’t come home that night the first person police want to talk to is Urquhart, the boyfriend with a motive.

“Old school” detectives grill a lot of suspects in an investigation that is to drag on for years, but none as often as Urquhart. A weaker person might have made a false confession just to end it.

But all that comes later. As Thursday night turns into Friday morning, things look more sinister every minute.

WHEN BEANIE BANDIT THREATENED ME WITH A BRICK

Gary Heywood’s beloved FJ Holden

Heywood’s family know he would never leave his beloved FJ Holden unless forced to.

So when a local policeman finds it parked haphazardly in the main street just before dawn, windows down and too far from the kerb, the Heywoods are sure their Garry is no runaway Romeo.

So whoever abandoned his car is the last to see their boy, dead or alive.

Nearby, in Mooroopna, Gary Heywood’s girlfriend Gail hears the 8am bulletin. The names of the missing are broadcast. Gail is surprised to hear Garry went to the concert but she’s sure he hasn’t run away: she knows he was flat broke and had a week’s pay owing.

It’s a big news day. On Gail’s bus everyone is reading The Sun.

The notorious prisoner William O’Meally has attacked a warder in Pentridge. The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies, has announced his retirement. The countdown to decimal currency, dollars and cents, is down to three days. And a Sydney detective has joined the hunt for the missing Beaumonts.

But soon the Shepparton case will take over from all those.

The town’s toughest cop was good at handling brawling fruit pickers and local thieves but as an investigator he made a good bouncer, which might be why he’d moved back to the country from working in homicide.

But the hard man did one good thing.

Late that first day, he retrieved Garry Heywood’s car from the family, who’d taken it home that morning. By chance, Garry’s father stopped his younger son, Allen, from washing the car — an instinctive decision with far-reaching consequences.

The policeman locked the FJ in a garage, where fingerprint experts later dusted it to reveal its secrets.

The hunt for suspects

HIS former colleagues from the homicide squad, meanwhile, helped him make life hard for Ian Urquhart and his friends.

The second day, Saturday, a man riding his bike over a bridge on the highway east of town spotted Abina Madill’s handbag lying in the creek bed. It says Heywood’s car went that way but it doesn’t help.

Shepparton was in shock, then under siege. By the fifth day, an army of volunteers combed the rough country along the Goulburn River and reporters were entrenched. Newspapers dropped the euphemism “grave concerns”. This was a murder case.

Claims the missing pair had been spotted in Mildura started a spate of “sightings”. Police started the needle-in-a-haystack search for travelling fruit pickers who had swarmed through the Goulburn Valley orchards, a waste of time that would go on for years. The first week there were reports of girls matching Abina’s description at Mildura, Kerang, Sale, Wodonga and Sydney.

More strongarm detectives came from Melbourne to interrogate Ian Urquhart and his friends Peter Hazelman and Ernie Maw. They even pulled in Garry Heywood’s broken-hearted father Charlie and worked him over while others searched the stricken family’s house. It was easier than proper police work.

By the end of the second week, the experts who reckoned they could “smell a crook” realised they were in for a long investigation.

They couldn’t have guessed it would see most of them out of the job.

The bodies are found at Murchison East

PETER Jacobi would later become a policeman. But in 1966 he was a suburban teenager who loved coming up to go shooting around his grandparents’ place at Murchison East, a speck on the Goulburn Valley highway 37 kilometres south of Shepparton.

Jacobi and his mate, Phillip Ashton, got off the train before noon on Saturday, February 26. After seeing Jacobi’s grandparents they cut across the paddocks to the bush beside the river. As they crossed the fence into the trees they smelt something dead.

An hour later, returning, they smelt it again. Then saw it. A human corpse — shockingly decomposed, unmistakably female. They bolted for the nearest farmhouse.

When the police arrived, the farmer, Jack Cassidy, told them he’d smelt something near a clump of saplings in his paddock not far from the girl’s body. That’s where they found the remains of Garry Heywood, a bullet hole in his left temple.

Mr and Mrs Heywood were bottling fruit to keep themselves busy when Garry’s big sister Lorraine arrived with her husband and terrible news.

“Mum and Dad,” she said quietly. “We think they’ve found Garry’s body with the girl’s …”

The gun they lost interest in

THERE were clues near the bodies. Two shiny spent .22 shells and a piece of black plastic that the police ballistics expert identified as from a Mossberg .22 semiautomatic rifle, an American model well-known but not common in Australia. The bullet taken from Garry Heywood’s skull matched a Mossberg.

With a little luck and painstaking work a clue like that could lead straight to the killer. With some bad luck and slipshod work, it led nowhere.

The problem was not too few leads, but too many.

While investigators wasted thousands of hours and kilometres tracking a suspect blue Holden that would turn out to be a red herring, the search for the Mossberg rifle was half-hearted.

They listed people who’d bought Mossberg rifles from Goulburn Valley gun dealers and started to trace them. But the searchers lost heart when they found that in addition to the 149 Mossberg .22 “self loaders” shipped directly to Australia by the manufacturer, many more had been imported independently by dealers and private buyers. In the end, police test fired 353 Mossbergs but lost interest.

It was the worst blunder in an investigation littered with them.

Guns sold by registered dealers had to be logged in an official Gun Dealer’s book with details of the buyer but the simple process of checking the books happened at only a few stores around Shepparton. Records from the Myrtleford sports store, barely an hour’s drive from where the bodies were found, were apparently not checked.

The Myrtleford records would later be destroyed by water damage but in 1966 were likely still available. The dealer’s book there should have included a Model 352 K Mossberg sold about 1958 to a prosperous farmer as a gift for his adopted teenage son — the son who had the rifle on Gawnes’ farm at Ardmona in 1965.

Seven weeks after the murders, 1000 people had been interviewed, a number that would triple over the next four years. Because the killer wasn’t one of the “obvious” suspects, nor among second-tier suspects, the investigators floundered. It didn’t help that some were still convinced that Ian Urquhart was guilty. They would persecute him until he eventually left town, then Australia.

How killer slipped through their fingers

No-one now knows — or admits — why police turned up at Gawnes’ Ardmona farm in the autumn of 1966, asking by name for the sullen young sharefarmer who had headed north to the Riverina only weeks before with his pregnant wife, Lesley. The Gawnes assumed they knew he had a Mossberg rifle and wanted to test it.

Reg Gawne opened his wages book and found a forwarding address: R. Clark, “Sunny Plains”, Mayrung, NSW.

The policeman said he’d get “the boys up there to pick him up.”

But he didn’t.

No one came for the young wife basher, at Mayrung or any of the many other places he would go over the next 19 years. Lesley would finally break away from him but was bullied into leaving her children with their father for several years. He, meanwhile, became almost invisible.

He drove unlicensed for years, rarely put his name to any documents and, when he did, fudged dates and place names to make it look as if he’d never lived near Shepparton in 1966.

He moved from abattoir to share farm to labouring to security work to yet another farm. He soon trapped another woman who answered a housekeeper advertisement and fell pregnant to him. Her life was no better than Lesley’s but she stayed because she had two fatherless children and no better prospects.

But the moody farmer soon proved how weird he was by faking his own drowning in the Hume Weir, sneaking to Melbourne and taking a job as a tram conductor. He and his “housekeeper” Colleen were reunited three months later, just in time for the baby to be born.

He would change jobs over and over. One was on a farm near Shepparton. Once, driving past Murchison, he and Colleen recalled the notorious murders there and warned the kids not to trust strange men.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST iTunes | RSS

The Donvale rapes

THE Heywood-Madill inquest came and went in June, 1970.

The coroner blamed a person or persons unknown. Lesley’s divorce was completed the next month. Four days later a young woman was raped at home in Donvale; her children asleep, her husband out for the evening.

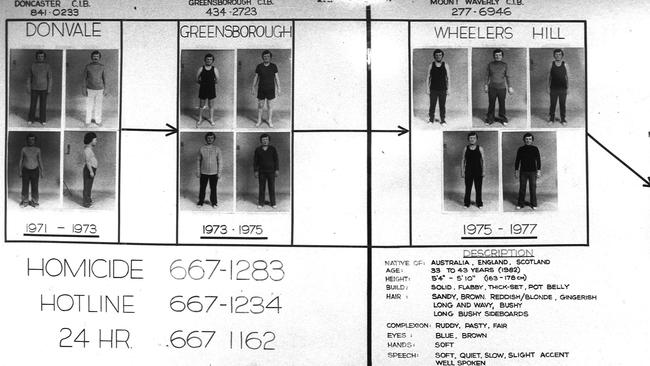

It was the first of many rapes of young mothers in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs in the 1970s. Few resisted because of the threat to their children. All were attacked when their husbands were out. The rapist must have watched for days, waiting his chance.

Police couldn’t catch the rapist but they knew he carried a butcher’s knife, stockings to tie his victims and walked silently in bare feet. They also built a composite set of fingerprints from samples lifted at three crime scenes.

For 11 years the Donvale prints lay dormant. In 1982, a young fingerprint expert, Andy Wall, put together a pin board of “most wanted” prints found at serious unsolved crimes. The Donvale prints went up with others.

Wall was hunting for older prints to add to the board when something caught his eye: a tiny partial print from a car in 1966 reminded him of the Donvale rapist’s.

Wall, a migrant, knew nothing about the Shepparton murders.

But his boss did.

The prints found on Garry Heywood’s Holden had been secret for 16 years. Now they knew the 1970s suburban rapist was the 1966 Shepparton killer. They had everything but his name.

The print breakthrough was kept secret.

How the Mr Stinky name came about

But four months later a Press reporter, Steve O’Baugh, overheard a policeman mention Shepparton. O’Baugh asked Sydney police contacts if any Victorians had been checking finger prints over the 1966 murders. They had.

O’Baugh broke the story under the headline KILLER PRINT CLUE.

By then a group of Shepparton detectives had been quietly working on it for months. Their bosses had to go public.

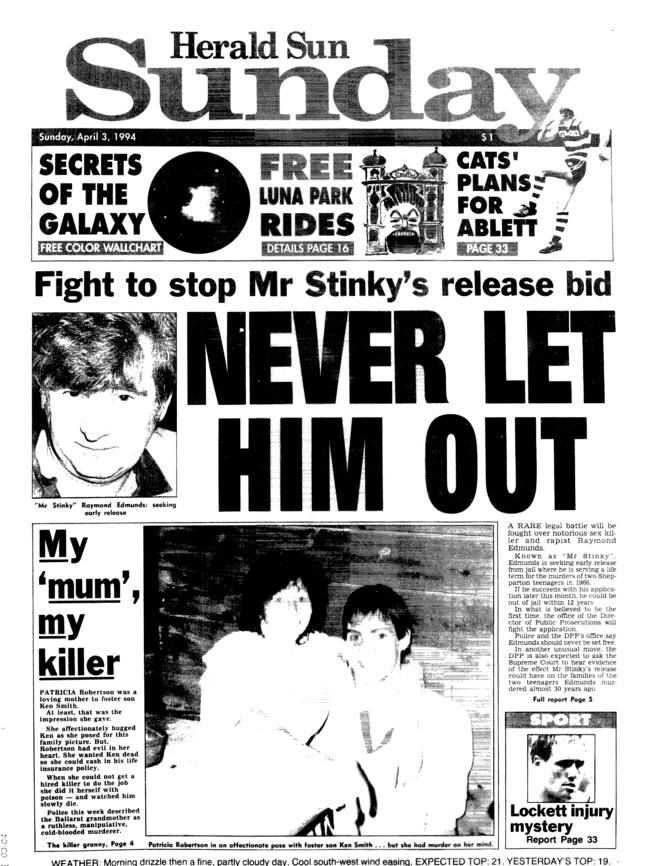

They released a bust of the wanted man compiled from rape victims’ descriptions. Witnesses said the rapist was podgy but strong, with sandy hair. Some suggested a “Scottish or Northern English accent”; others mentioned an odour. Sheer novelty value meant the bust, the supposed accent and vague odour overshadowed better clues: bare feet and butcher’s knife.

The Sunday Press needed a name for the unknown man to make a snappy headline.

Chief subeditor Lyall Corless rejected “Pongo” and “Mr Smelly”. He wrote “Mr Stinky” and it stuck. Every other media outlet adopted it, reinforcing the impression the wanted man had a “foul odour” — and a British accent.

None of which made it easier for the detectives hunting a man very good at not being found.

Dennis Hanna had worked on the Donvale rapes in Melbourne. Now, as head of Shepparton detectives, he led the hunt. Under him were local policemen who’d grown up with the Madill-Heywood mystery. One of them, Norm Gillespie, had gone to the concert, aged 15, hoping to see Abina Madill’s younger sister Roslyn. For him and another local cop, Ken Mansell, it was personal.

Hanna, Mansell, Gillespie and their colleague Denis Lucas had worked feverishly for months, compiling massive lists of names from every data base possible, hoping to identify potential suspects by checking who’d moved from one district to another — a huge elimination exercise compared with the Mossberg rifle inquiry their counterparts had abandoned in 1966.

And they probably would have caught the killer if he hadn’t stumbled into the trap first, all by himself.

How Mr Stinky was caught

IT was in Albury, just across the border, on March 16, 1985. A shop worker in Walton’s store saw a man exposing himself in a car outside. Her boss called the police.

They didn’t even handcuff him. But because it was NSW, not Victoria, even flashers were routinely fingerprinted. Which was why, five days later, the flasher’s prints arrived at the central fingerprint bureau in Sydney.

Ray Butterfield had scanned hundreds of prints that day but these leapt out at him, especially the scar on the little finger. Eight months earlier, Victorian detectives had come to scour the files to match the print he had in his hand. Here, in the mundane way of the real world, was a coup. A double murderer and multiple rapist had blundered into the net.

The name they had wanted since 1966 was on the back of the form.

He was arrested next day.

Before he signed his statement many hours later he was asked if he had any disability.

“I’m fit and healthy,” said the quiet man. “But I must be sick in the head. I think I need destroying.”

Edmunds pleaded guilty to two counts of murder, three of rape and two of attempted rape. He was sentenced to two terms of life imprisonment.

He remains a suspect for the murder of Elaine Jones near Tocumwal in January, 1980.

MORE ANDREW RULE:

THE MODEL, THE PSYCHO & THE GARDEN PARTY

CHOPPER & SYD: A TALE OF TWO IDIOTS

Originally published as How police finally caught up with notorious rapist and killer Mr Stinky