How NZ used guitars, not guns to bring end to ten years of war in Bougainville

Against all odds, the New Zealand army managed to end the Pacific’s worst civil conflict, achieving one of the greatest peacekeeping operations in history. Here’s how they did it.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Guitars, not guns finally brokered peace in conflict ridden Bougainville, as New Zealand delivered the solution to help free the Pacific from the grip of its worst civil war.

Their approach was mocked at first but it worked and became one of the most successful peacekeeping missions ever.

The ten-year war led to 20,000 deaths and 14 failed peace attempts. During this shootings, rapes, murders and riots became the new-normal as locals clashed with outsiders.

New film Soldiers Without Guns tells how the NZ mission spelled the end of the war.

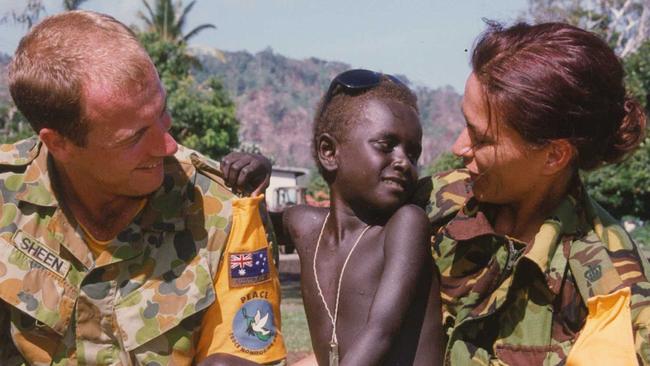

Their 15th peace effort, Bel isi, (meaning ‘at ease’) used three ‘weapons’: music, women and faith as the voice of reason to lower weapons.

The women were a calming point of contact for the locals, the music helped break the ice and Christianity served to unite and diffuse hostilities by showing they had like-minded beliefs to the locals.

Director Will Watson said the Kiwis succeeded because they put culture first, they listened to the locals and showed genuine compassion.

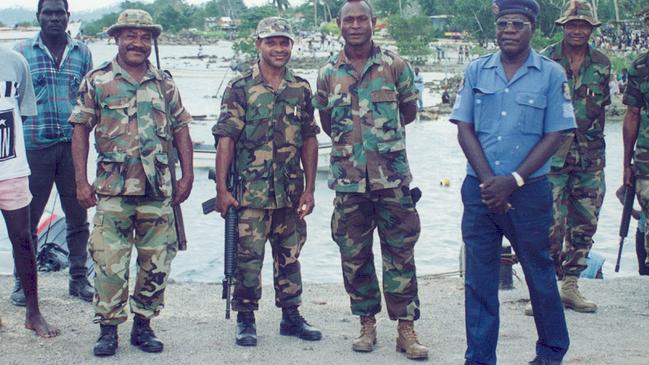

In 1997, Australia teamed up with NZ and Pacific troops from Vanuatu and Fiji to help Bougainville achieve the peace they wanted but didn’t know how to get.

Under the guidance of now-retired NZ Brigadier Roger Mortlock, army major Fiona Cassidy and kiwi troops landed on Bougainville in the middle of a ‘minefield’.

MINE LEAVES LOCALS SHAFTED

The conflict began when Rio Tinto established the Panguna mine in the 70s. The company jumped on the discovery that Bougainville had the world’s largest source of copper ore.

Locals said they’d rather die than give up the land but the PNG government used police to take it.

The $400m mine employed thousands, produced 60,000 tonnes of waste daily and became a major revenue source for PNG.

Locals were angered by the influx of non-natives and Panguna’s environmental toll. Bougainville also wanted total independence.

All of this was ignored fanning the flames of discontent.

TEN YEARS OF VIOLENCE

By the 80s, the mine was centrepiece of civil war. Locals demanded billions in compensation but were refused.

Resistance leader Francis Ona fuelled an uprising using fighters to sabotage the mine. PNG responded with force and killed hundreds.

The rebels started their own government and the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA), led by former PNG soldier Sam Kauona.

Many miners left the island fearing violence. In 1988 mine production stopped and PNG pulled its defence giving locals the impression they had won the war, but it was far from over.

PNG ordered a naval blockade to starve Bouganvilleans into submission, killing 1500.

Anarchy ensued on the island and locals turned on BRA. PNG seized their chance to arm these residents to fight the rebels.

As Ms Cassidy puts it, it was “brother on brother”.

THE PEACE PLOT

As PNG plotted to eliminate BRA, local women worked to achieve peace.

After PNG tactics failed, the Kiwis convinced opposing delegates to come together in NZ for peace talks.

Bougainville indicated it was ready for peace and accepted that NZ would lead the 15th attempt to get it.

“We were scared of people with guns. By bringing in people that did not have guns, that kind of approach was very important to the people of Bougainville,” Local nun Sister Lorraine said.

“We didn’t bring about the peace, the Bougainvilleans came to the position they wanted peace. What we did was provide the opportunity for them to breathe … they wanted us there to help,” Ms Cassidy said.

PNG’s new leadership offered amnesty to all sides of the conflict for atrocities committed and against all odds the kiwi’s mission to kill a war with kindness succeeded. From here a peace accord was signed signalling the end of the war.

Ms Cassidy said Bougainville serves as a global reminder that cultural understanding is crucial for peace.

Mr Watson felt the NZ solution was a leading example in conflict resolution.

“The world is battling with entrenched conflicts and the highest number of refugees since World War II. When Australia and New Zealand work together magic happens,” he said.

Soldiers Without Guns is screening at selected theatres for a limited time. For session times visit https://au.demand.film/soldiers-without-guns/

AUSSIES HELP IN THE AFTERMATH

Adrian Fowler was 16 when we went to Bougainville to help in the aftermath.

In 2008, ten years after NZ helped to diffuse the war, he arrived to teach locals English and maths.

“It shocked me that these people had the biggest, brightest smiles despite all the terrible things that happened to their land and people,” he said.

He formed a strong bond with local school leader Kinsford over their love of soccer.

The pair teamed up to host matches.

“It was a five-aside match but we only had five pairs of boots so everyone wore one boot. This was eye opening for me … the joy of playing with one boot was astounding. I took for granted playing with two on mowed lawns with a pumped up ball back home,” he said.

While most of the locals welcomed the students, Mr Fowler, who is now a News Corp picture editor, said they had to keep their guard up and be wary of tribes that considered Australians a threat.

He said the effect of war was still clear: “The poverty, lack of general health services, infrastructure. There was an inability to have much optimism for their land and economy after it was ripped up and destroyed.”

“We couldn’t imagine the things people saw or had to do (during the war) just to survive.”

Originally published as How NZ used guitars, not guns to bring end to ten years of war in Bougainville