How did NSW’s milk economy get so complicated?

Farmers and retailers have long been at odds over how the dairy industry should be run. For farmers, the price cut for bulk supermarket milk was a death blow for many. But as with everything dairy, there are contrary views, writes Tim Blair.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Milk is a simple enough substance, easily obtained and impressively versatile in its uses.

But add politics, economics and competing interests, and suddenly milk becomes a very complicated issue indeed.

This is particularly the case in NSW, where dairy farmers and retailers have long been at odds over how the dairy industry should be run and how it should proceed.

The eight-year supermarket milk pricing war is an especially hot topic, even after it was ended earlier this year.

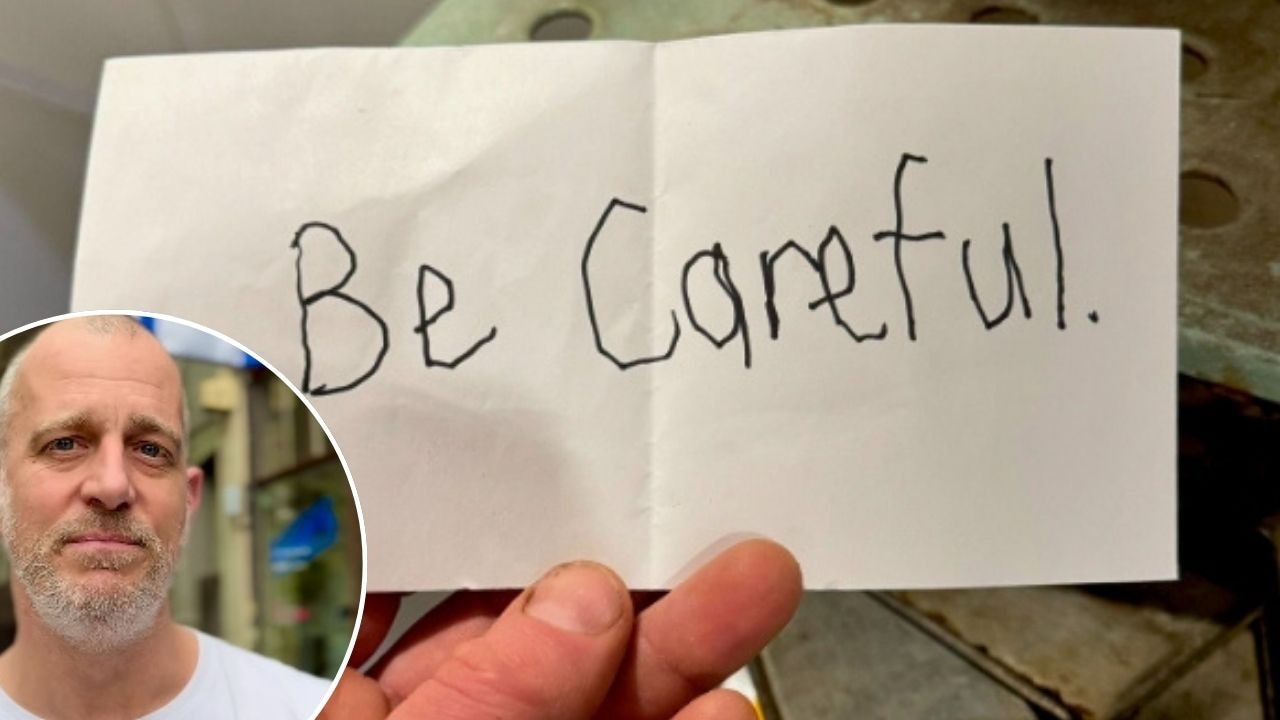

Farmer Nic Dibden recalls the exact moment he learned from morning television of Coles’ move to slash bulk retail milk prices from $2 to $1 per litre.

“I nearly choked on my Weeties,” he says, in the Tilba Real Dairy he runs with wife Erica.

Sci-fi milking machine became a tourist attraction

That price cut for bulk supermarket milk was immediately followed by rival chain Woolworths, which according to Dibden and others “destroyed” much of dairy farming in NSW.

Yet, as with everything dairy, there are contrary views. As one industry heavyweight put it: “Whatever we charge for milk has nothing to do with what farmers are paid. We could give it away if we wanted to, and it still would not alter the price at the farmgate.”

That quick analysis is supported by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, which found after an 18-month investigation into dairy pricing that “the price set by retailers is arbitrary and has no direct relationship to the cost of production for the supply of milk …

“If supermarkets agreed to increase the price of milk and processors received higher wholesale prices, processors would still not pay farmers any more than they have to secure milk.”

READ MORE

Coles to pay dairy farmers $5.25m amid ACCC allegations

Aussie dairy farmers getting milked for all they’re worth

Many farmers who are seeking a guaranteed floor price for milk and other market interventions will dispute the ACCC’s findings.

Sid Clarke, whose dairy operation is in Ladysmith, east of Wagga Wagga, believes his industry has been in decline ever since it was deregulated and opened to free market forces in 2000.

“Deregulation was the catalyst,” says Clarke, pointing to a subsequent fall in the prices received by farmers, down from 54 cents per litre in 1999 to an average of 43 cents now.

Deregulation is also widely blamed for the sheer extent of dairy closures. Around Wagga, there are many more abandoned dairies than ones that are functioning.

But dairy closures have long been a feature of the industry as it became more mechanised and efficient. This was the case even before deregulation. From 1980 until 2000, the number of dairy farms around Australia was almost halved.

The mechanising process continues. The Myall River Pastoral Company earlier this year announced plans for a 280-cow robotic dairy farm at Bulahdelah in the NSW Mid-North Coast.

In one area, dairy farmers are very much at an economic disadvantage compared to others working in agriculture. Due to the nature of dairy farming itself, dairy farmers are restricted in the ways they can manage supply and demand.

Put simply, cows need to be milked and milk does not keep for very long.

“We’re the perfect target,” explains Emma Elliott, a farmer’s daughter who is now director of Dubbo’s Little Big Dairy.

“Wheat farmers can put grain in silos for three years and wait until prices improve. But we have to milk our cows. It’s a welfare issue. And then we have to sell it, quickly.”

Elliott and her husband Jim are young players in an older person’s caper. The average age of all Australian farmers is 56. In Ladysmith, Sid Clarke is only now at 77 preparing to hand the full operation of the farm to his 57-year-old son.

Although the Elliotts agree with others in the dairy industry that an increased farmgate price is crucial, they are by virtue of their relative youth and competitive, hardworking personalities less inclined to pursue regulatory support.

Instead, they are betting on technology, innovations in quality and a single-source business model – which controls all aspects of production, from milking to delivery – to build on their success.

Above all, says Elliott, dairy farming needs “a younger generation being gutsy”.

And NSW will always need milk. Finding a way of putting it on shelves that keeps everyone happy, however, is a whole different story.

Originally published as How did NSW’s milk economy get so complicated?