Grand Dames of NSW: Inspirational women and their amazing stories

She fought for equality in the face of old-school expectations of a Greek husband, learning how to drive and studying against her husband’s wishes. But Giota Hrissis took it one step further after he told her she could never smoke — she took up the habit at 80. READ HER STORY AND OTHER AMAZING FEMALE TRAILBLAZERS

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They have lived through wars, recessions, polio outbreaks, massive technological advancements, injustices and the sexual revolution.

This special Sunday Telegraph report celebrates the grand old ladies of NSW.

Often out of sight, or even forgotten, these ordinary women have led extraordinary long lives and today share the wisdom and wit of lives well lived. Age has wearied them, but not their memories.

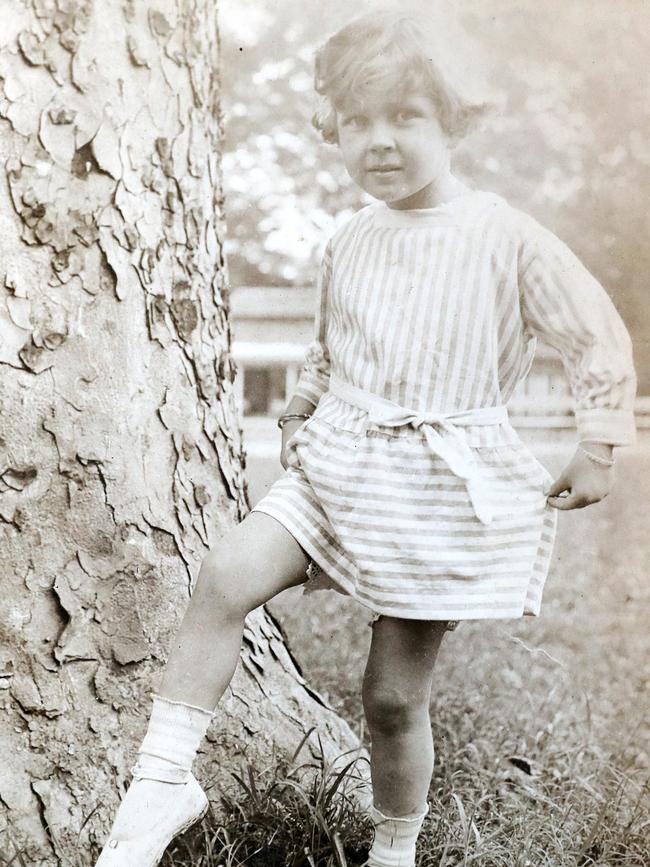

JOAN EVANS

Erina , Central Coast

Age: 100

Joan Evans turned 100 last week and because of COVID-19, she celebrated her birthday at her Erina home via phone with her family — five children, 14 grandchildren and 25 great-grandchildren.

Mrs Evans said she has lived an “extraordinarily lucky life” where sliding door moments ensured she lived to receive that milestone letter from the Queen.

Born on August 17, 1920 in Calcutta to British parents who ran a paper mill, her early life was exotic, including a boarding school education in the Darjeeling on the eastern side of the Himalayas.

World War II derailed a Cambridge University education.

“My father sent my mother and I to Canada where we would be safe. I was booked into Toronto and I finished my degree and got a diploma in health and physical education,” she said.

War was still raging in Europe when Joan and her mother planned their trip back to India to reunite with her father, but they went via Pearl Harbour, the first of her sliding door moments. A wharfies strike in Canada held them up a week.

“If we had sailed on the day we were meant to we would have been in Manila and taken prisoner of war by the Japanese,” Mrs Evans recalls.

“As it happened, we went directly to Honolulu and we could see the planes up north over Pearl Harbor. We thought it was practice and as were getting into the harbour they dropped bombs on either side of us. We were very lucky.”

MORE FROM JANE HANSEN:

Youth mental health worsens due to COVID-19, report reveals

Teo v Woo: Surgeons face off over private medical fees

After a week in bunkered down in the Royal Hawaiian hotel, the then 21-year-old and her mother tried to get a ship convoy out, but they were all booked with American women and children returning to the US. Some of those convoys were also bombed.

She finally made her way back to India where she was employed as assistant director for health and physical education for all of Bengal. She also volunteered at the Red Cross, helping soldiers who were flown back from Burma, then she volunteered for the Women’s Voluntary Service which took her to Burma where she had her second sliding door moment.

“When I was leaving from Calcutta, of the two planes that were sent in, one pilot had a cold and couldn’t fly so I was put in one plane and the second one was sent off for stores. We just got out of the plane in Burma and were walking towards the operational tent when the second plane circled round and next thing another plane coming back from operations collided in the air and the plane coming in, which I should have been in, went straight down and burst into planes. That was fate. That made me think: ‘This is war and things are serious and not going to be fun’,” she said.

The pilot who died was Richard Evans’ best friend. Evans was the strapping Aussie pilot young Joan immediately fell for.

“When I met Dick, every morning we’d take a van, it was like a Mr Whippy van with a window that flipped down, and we would take them their morning tea,” she said.

“All the planes were hidden in the jungle in camouflage nets, so we would go from one to the other. When I got to Dick’s I thought: ‘What a scruffy bunch, no shirts on’ because it was so hot, then I saw this young man coming up and I thought: ‘He’s the only decent one among them all’. He also thought I was a good sort because he kept seeking me out every time.”

But love in the time of war was terrifying.

At the height of the fighting, while he was engaging a Japanese fighter, Evans’ aircraft was hit from behind. The canopy flew off and he was thrown out of the aircraft.

As his parachute opened, he heard an aircraft he feared might be an enemy coming to finish him off. But luckily it was a squadron colleague.

After two weeks in hospital he returned to combat.

After the war, Dick was repatriated via the air force but Joan had to find her own way from Burma to Dabee, an impressive sheep farm in Rylstone, central NSW, first taken up by the Evans family in 1819. But the 25-year-old had plenty of grit.

“I worked my way down to Colombo and when I flew across from Colombo it was the longest without stopping, 19 hours in a converted Liberator,” she said.

Initially shocked by the dry Australian countryside, when she arrived at the lush central tablelands property she was impressed.

“I was really a very lucky woman,” she said.

In 1946, Joan Fawcett married her fighter pilot.

“I went into a wonderful family and had five children and was very happy there,” she said.

Dick went into local politics as a shire councillor before he was appointed to the NSW upper house in 1969, where he served for nine years.

By 1976, Joan and Dick separated and Dick remarried, but Joan continued her impressive work with the Red Cross, which she continues today.

After Dick’s wife died in 2006, Joan stepped in to give him great support in his last two years of life.

“He was living up the road in the nursing home, I could walk up to the nursing home. He was there for three years and that was a nice thing. It was a great friendship,” she said.

“I used to take him for drives and it was a nice thing. Then he got a bit of dementia and didn’t last long but it was a good ending to our lives because we had been very happy for more than 30 years, a long time.”

Her forgiveness is one of the most inspiring things about Joan, youngest daughter Soozi said.

“That is mum, she has this default mechanism and it has spread to us, it is an amazing attitude. That is why she inspires us all.”

Joan has two treasured awards: The Rylstone Council Service award 1984 and the Red Cross Distinguished Service Award.

Her philosophy in life is: “Be positive, put sad times and wrong judgments behind you. We’ve all made wrong decisions, turn your head the other way and get on with it.

“War taught us that, we saw dreadful tragedies and we just had to get on.

“I think it brings contentment in a way, you get on with it and finally you feel happy.”

Asked what other younger women she admires, she can’t go past Queen Elizabeth.

“My dear Queen, Queen Elizabeth II. I think she has been a wonderful woman and she has had great problems in her life and has faced them wonderfully, I admire her,” she said.

KIT BRIGHT, OAM

Moss Vale

Age: 81

What life would you imagine for an octogenarian in a purple twin set who wins Country Women’s Association awards for knitting? Some might think a simple life of a wife and mother but Kathleen “Kit” Bright took a different path.

Kit was born in Fairfield in 1939 and barely saw her father, who was only home for 10 days in her first five years between fighting in the Middle East and Papua New Guinea.

“He dealt with the Japanese, I know for a fact, and I don’t think many of them came back unaffected and we will leave it at that,” she said.

In 1946, polio was raging in Sydney and Kit succumbed.

“I had polio when I was seven but I was the lucky one, some of the kids went back to my class in irons and leg braces. I just have some residual things, nothing more than a pain in the neck — but many have that at this age, so get up in the morning and do your best, that is my sentiment.”

Career options for young women remained limited in the 1950s. At 17, Kit was inspired to take up nursing as the new Fairfield Hospital was built in her neighbourhood.

“On my worst days I’d say to my mother: ‘Why did I go nursing?’ and she said: ‘This is what you said at the time Kit, it is something you can do to help people but you would get paid’. I had to do something to get paid, so I stuck with that.”

Kit went on to run Liverpool Hospital as director of nursing but never forgot her humble beginnings.

“In my training days, one of the things we had to remember is every sweep of the veranda had to be two-thirds over the previous sweep. Who would go into nursing in this day and age if they had to sweep verandas? But in ‘56, there was nothing unusual in that, that is what they did.”

Kit dreamt of marriage and children but it never happened.

“I don’t know that I devoted my life to nursing, it is how it was,” she said.

“I had great plans at high school to get married and have eight kids. Life brings its problems and its pluses and minuses and there is no point in fussing too much one way or the other in my opinion. I just say, get up in the morning and do the best you can.”

Kit’s career took her all over the world before entering management.

“For a long time I was director of nursing at Liverpool hospital and people say I should write a book and I say I wouldn’t dare.”

What amuses her now is the complaints over getting a flu shot to work in healthcare.

“When I started nursing we all had vaccinations for everything on God’s earth — TB, this, that and the other, it was a fact of life. We had to do it, and like many things in life that is how it is,” she said.

And she broke through glass ceilings.

“I finished my career at Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane as chair of surgery, I went up through the ranks.”

In 2016, Kit was awarded an Order of Australia for her services to nursing and women and spends her retired days knitting and gardening. She remains an enthusiastic member of the CWA.

“I’ve belonged to CWA since 1986 and hung by since 1978 when my mother joined. If anyone needed a hand, the thing I have heard all my life is ‘Kit will do it, Kit will help, Kit whatever’, so it has been a great outlet,” she said.

In terms of young women who inspired her, Jacinda Ardern has her respect, especially since the pandemic.

“I think she is doing her best against all odds, I think she is doing very well,” she said.

“I also think highly of Penny Wong, she speaks very sensibly. She doesn’t talk off the top of her head like others.”

SISTER ANTHEA GROVES, OAM

Paddington

Age: 82

The musical Sound Of Music famously sang: “How do you solve a problem like Maria?” regarding a mischievous nun. But you could replace Maria with Anthea, for Sister Anthea Groves has gotten herself into mischief all her life.

Born with a twin brother in the Snowy Mountains town of Tumut in 1938, Anthea Groves loved having fun.

“At school I was, let’s say I liked pushing boundaries a bit,” she said.

“I obeyed what I had to but I liked to have a bit of fun as I went along.”

And that was a streak that stayed with her. Like so many of her generation, she chose nursing as one of the few women-friendly careers on offer.

“I made up my mind I wanted to do nursing, so I made an application to go to St Vincent’s. I liked helping people, it is part of my nature I suppose, a sensitivity to needs,” she said.

In 1956, at the age of 18, she joined a St Vincent’s Hospital four-year, live-in nursing program shepherded by The Sisters of Charity.

“My four years of training were challenging, the Sisters of Charity tried to ‘tame’ the girl from the bush,” she said.

But that girl had discovered Sydney’s night-life.

“We were young and we had extraordinary social activities,” she said.

“Sydney was different, we loved the Cross and the night life that was around and for me it was so new, it was great.

“Going out at night and not getting home in time and getting in strife … I had to be home by nine or 10 and sometimes that wasn’t always adhered to.

“The nuns were hard taskmasters.”

Anthea was grounded for a month, more than once. But, to everyone’s surprise, on completion of her nursing training she decided to join the Sisters.

“I often said if you can’t beat them you join them, in jest,” she said.

“I thought they were tough but they led wonderful lives and did great things and you couldn’t say they brainwashed us, I wasn’t that type of person.

“There was something about their commitment to religious life that made me think there was more to life than just doing what I was doing. So in 1962 I entered the order.”

But Sister Groves was still a young woman who was acutely aware of what she had given up.

“Yes, I think one of the difficulties is when you become a young nun and you are mixing with young adults,” she said.

“In some ways it is a wonderful thing because you do experience all the emotions of young people — you are not excluded just because you have a habit on.

“But you know what you are doing if you give up having a family and whatever because you have the opportunity to consider it, and I had that when I was training.

“It wasn’t as if I had a life where I just came to work and went home and went to bed. I did live to the full and I knew what I was giving up really.

“It is amazing when you make your commitment and I presume it is the same for a married person.”

But nursing was her true love.

“Being able to help people, some of the older, some Aboriginal, some of the disadvantaged people from the Cross, there was no distinction between who they were or what they were, they needed care and I thought it was a privilege to help them,” she said.

“It is great to finish a day’s work and know you have helped people.”

Donning the crisp black habit however, was not the end of that cheeky streak. Nor the end of her upsetting the senior nuns.

“I liked to do it my way, I didn’t like a lot of the restrictions and I got into trouble once because I went to a wedding of one of the doctors, a great friend of mine,” she said.

“We had grown up together young nurse, young student doctor and my theory of survival was never to ask permission, I didn’t always ask permission to do things, so I went to St Mark’s at Darling Point in my habit and I didn’t tell anyone.

“In those days you didn’t go to other churches. I know that but to my way of thinking it was more important to be present for a friend.”

But she was found out when doctors expressed how wonderful it had been for Sister Anthea to attend.

And again she ruffled habits when she lent hers to her doctor friends.

“They were doing a Sound Of Music tour and had gone out on the harbour and people coming across on the ferry rang Mother to say the nuns were out on the harbour,” she recalls.

“That was the type of person I was, I got into a lot of trouble but I didn’t see any harm in letting the fellows make a movie.

Her nursing career also took off.

Emergency nursing, intensive care and surgical nursing, midwifery training at Queen Victoria Hospital in Launceston on 1972 and a degree in Hospital Administration were all under her belt by 1977.

She then managed St Vincent’s in Toowoomba, where she was responsible for the convent, the nursing and hospital management for 10 years. Then she managed St Vincent’s Public Hospital in Melbourne until 1992.

Joan Kirner was then premier during that time and to this day, Sister Anthea nominates the late Ms Kirner as an inspiration.

“She was a great support to me,” she said.

In 1994, Sister Anthea returned to St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst in a patient liaison role where she mediated with patients, their families and staff and encouraged the opening of wealthy wallets to donate to the hospital.

In 2015 she received Kerry Packer’s widow Ros, following the Packer and Crown Resorts Foundation’s bequest of $10 million for organ transplants.

Sister Anthea was awarded an Order of Australia medal 2010 and, since her retirement in 2017, she has cared for older nuns in the order from her home in Paddington.

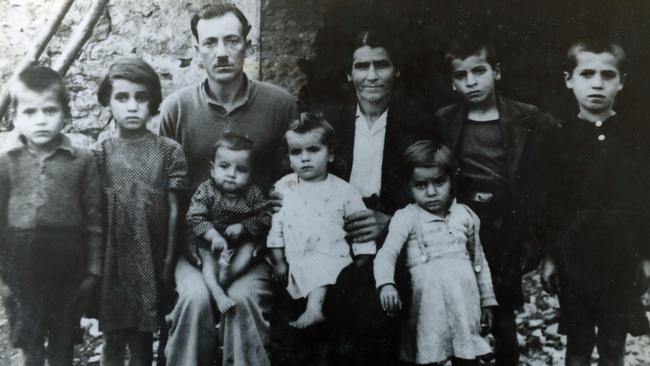

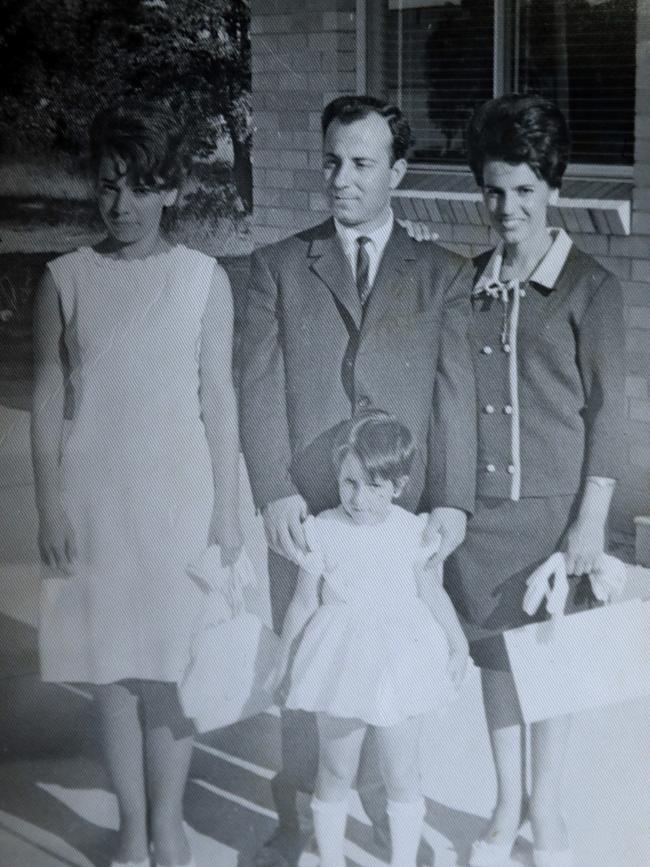

GIOTA HRISSIS

Russell Lea

Age: 81

In the year World War II broke out, Giota Koutsantoni was born in the beautiful Peloponnesus region in southern Greece. One of 10 children, the now 81-year-old former teacher from Russell Lea credits this with shaping her formidable character.

“It reflects my character, I am a very good fighter, I am a warrior,” she said.

She is a warrior for education, for equality, for fairness and she has fought for it in the face of old-school expectations of a Greek husband.

As she lights up a cigarette, she explained that her husband of 59 years, Stelios Hrissis — who died aged 90 in June this year — told her she could never smoke. She has now taken up the habit.

“I took up smoking at age 80,” she laughed.

“And when I turned 80 I said: ‘Now I am entitled to say and do anything’.”

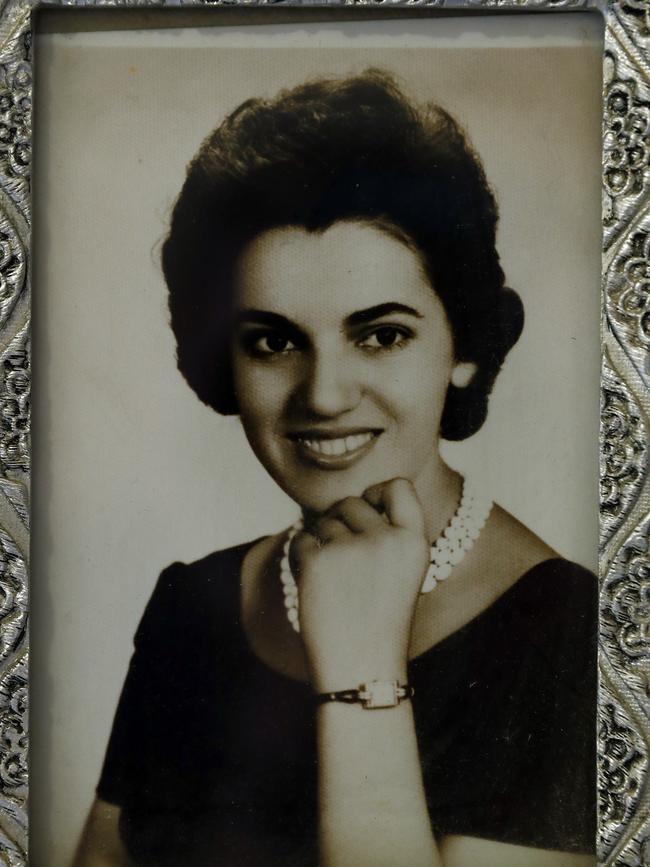

The smoking ban was perhaps the only time she obeyed her beloved, “a good man” she married in 1961 after corresponding with him from her Greek home.

They had met through a family connection and exchanged letters across the sea.

When she first came to Sydney earlier that year she had the same fear most Tinder dates would recognise — will he match up to the picture he had sent?

“He was very presentable, he sent a nice photo and I feared he may not live up to the photo, but he was very, very good,” she said.

“I was impressed. He was quiet and polite.”

The couple married later that year. Stelios worked as a painter and Giota worked as a dressmaker at Nobel Fashion, Oxford St near Taylor Square but, in her afternoons, she helped teach Greek children at the Greek Community School.

In December 1962, she gave birth to her only child, daughter Marcia, in their Marrickville home.

Suffice to say, Giota did not think much of childbirth.

“One child is enough. Giving birth is awful,” she said.

Like many Greek men, Stelios told his wife she was not allowed to drive. She defied him.

“We had a lot of arguments about driving. Most Greek women my age don’t know how to drive, I have to drive them everywhere. But I was a fighter, I was born in wartime.”

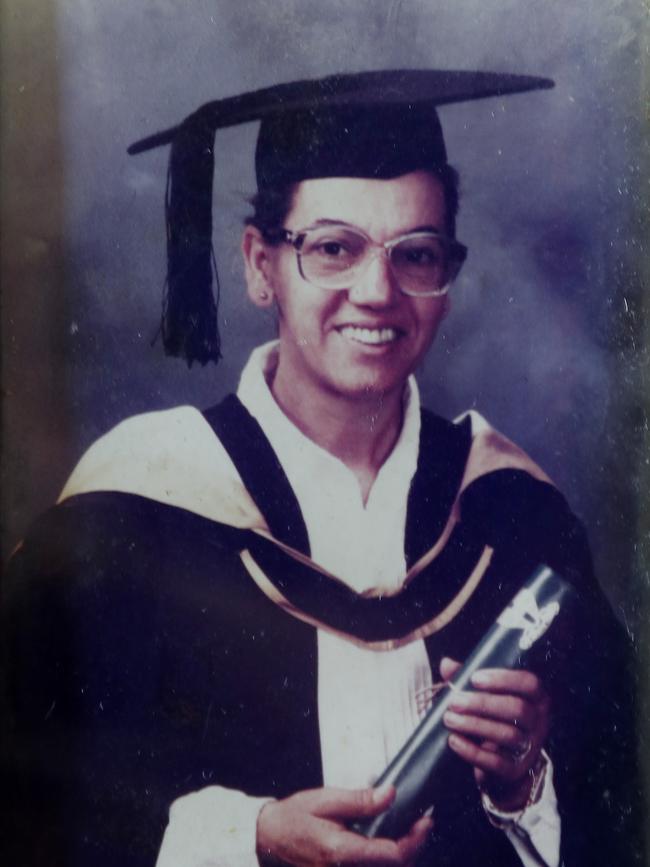

In her 40s Giota defied her husband again, by getting a degree in teaching from the University of New England.

“He thought I was doing it to get a boyfriend, this is how Greek men think,” she said.

“I did it through Open University and for four years we had a lot of arguments. He said to me: ‘I am the boss’ and I said: ‘Only a dog has a boss, not a human’.

“He walked out on me two times. He took some clothes and left and said: ‘I won’t come back until you burn the books’. I said: ‘No, I have 3000 books, I love reading and only Hitler burns books, not me’. He finally came home.”

For the past 20 years of their life, the couple lived in separate houses.

“I still looked after him but we argued a lot, he is very stubborn,” she said.

Giota went on to be a private tutor to help children keep the Greek language alive.

“I inspire them to respect the language and tell them it doesn’t matter what job you do, even if you are a cleaner, respect education because it opens your horizons,” she said.

She said she has been lucky enough not to have experienced racism.

“I did not, we lived in Marrickville, then Erskineville and people were beautiful and tried to help me with the English language when I needed it, so I did not experience those things,” she said.

“I think if you respect people they respect you. If anything, I am a bit racist, especially when I see some types who try to keep their women down. I hate that!”

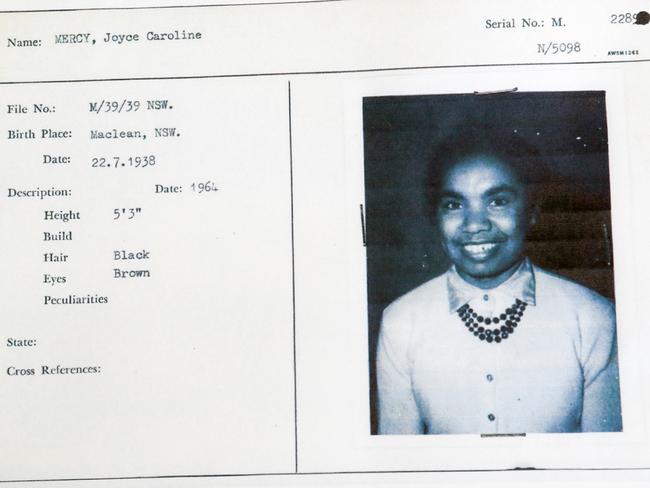

JOYCE CLAGUE, MBE

Ulmarra, NSW

Age: 82

Not many 82-year-old women have an ASIO file on them but then Joyce Clague is not your ordinary octogenarian.

Her “crime” was being Aboriginal and fighting for justice in the 1960s. Her ASIO file was only released last year, to the surprise of everyone.

A decade later she would be awarded a Member of the Order of the British Empire, a MBE, one she humorously refers to as her ‘More Black than Ever’.

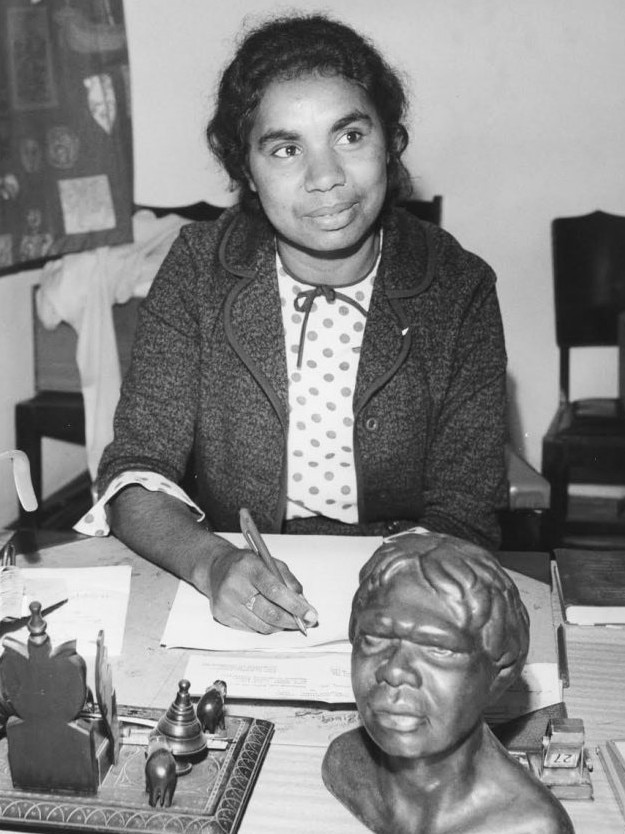

Joyce Clague’s daughter Grace arrives at her Ulmarra house and comes up to give her mother a kiss, speaking a language rarely heard. Joyce answers back. They are speaking Yaegl, a language kept alive by a young Joyce.

Joyce was born into institutionalised racism in 1938. This Yaegl elder may have had two strokes but she still remembers growing up on an Aboriginal reserve on Ulgundahi Island in the Clarence River on the NSW North Coast. Aboriginal families were forced by the Aboriginal Protection Board to live on the island under the strict control of a mission manager.

They were not allowed to speak their native tongue but, in what would be one of many impressive acts of defiance, Joyce learned it from her grandparents and today her four daughters also speak it.

“Because my grandmother couldn’t speak English very well, or my grandfather, it meant that the only way I could communicate was through the language, which was the Yaegl language,” she said.

“You had to speak English, they would correct you. I told them go and jump.

“They never found out it was me who was doing it, til this day.

“I knew from the beginning it was wrong, you just don’t take a person’s language and tell them not to talk it.”

Joyce worked hard at school and moved to Sydney where she began studying nursing at St Margaret’s. At 22 years of age she was recognised by the Australian Women’s Weekly magazine as an ambitious young woman.

But her career ended abruptly when she returned to Ulgundahi Island to care for her young niece after her aunt died. Joyce lost her own mother when she was only 10.

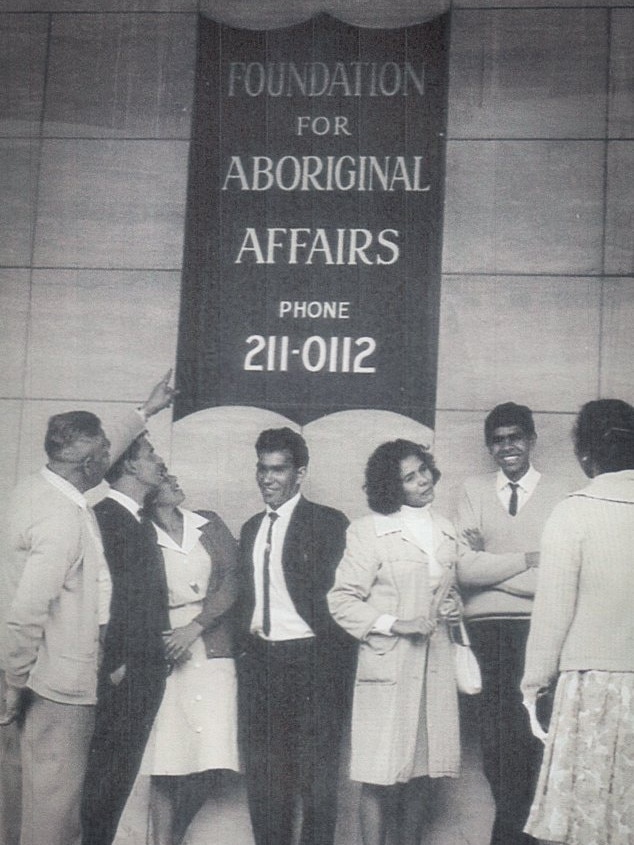

When members of the Aboriginal-Australia Fellowship (AAF) visited Ulgundahi Island, Joyce was inspired by the opportunity to create change.

The group took Joyce under their wing and she returned to Sydney where she became a civil rights activist and was instrumental in campaigning for Australia’s landmark 1967 referendum to include Aboriginal people in the census and whether the government should make laws for Aboriginal people.

Amid this, she met Colin Clague, a white man, and they married in August 1966.

In 1968, she stood for the Legislative Council of the Northern Territory and she embarked on an independent campaign, encouraging the enrolment of 6500 Aboriginal people.

She convened the Federation Council for Advancement of Aborigines in 1969. She was also appointed a representative of the World Churches Commission to Combat Racism.

She went to Geneva with the Council of Churches when her second child was just four weeks old.

Joyce was also a founding member of the NSW Women‘s Advisory Council to the Premier.

A photo of Joyce with Premier Neville Wran shows her tight grip on his arm, an image that captures her determination.

“That was true, I didn’t let him go until things were done, then I let him go. We were talking about land rights, housing and better living conditions, I had the ear of those yirallis (white people),” she said.

In 1977 she was awarded her MBE, in the 1980s she stood for preselection in the Australian Labor Party but perhaps her greatest achievement was lodging a native title claim known as Yaegl #1 in 1996.

It took in a large stretch of the Clarence River and its tributaries, on behalf of the Yaegl people and settled in 2015.

“It did take a long time and I didn’t give up because I knew that these yirallis, white people, they didn’t have long memories. I had a long time to think about this and dream about it.

“The seed was already there, it just needed to be nurtured.”

Colin and Joyce recently celebrated their 54th wedding anniversary.

“She is awesome,” is Colin’s summation of his wife.

Joyce nominates her four daughters as her inspiration.

Dr Leisa Clague lectures in midwifery at Sydney University, Associate Professor Pauline Clague teaches at UTS, Grace is a film producer and Yvette, who survived birth at just 26 weeks some 40 years ago and is blind as a result, is a talented clarinet player.

Originally published as Grand Dames of NSW: Inspirational women and their amazing stories