The unholy union of sly grog queen Kate Leigh and safe-breaker Ernest ‘Shiner’ Ryan

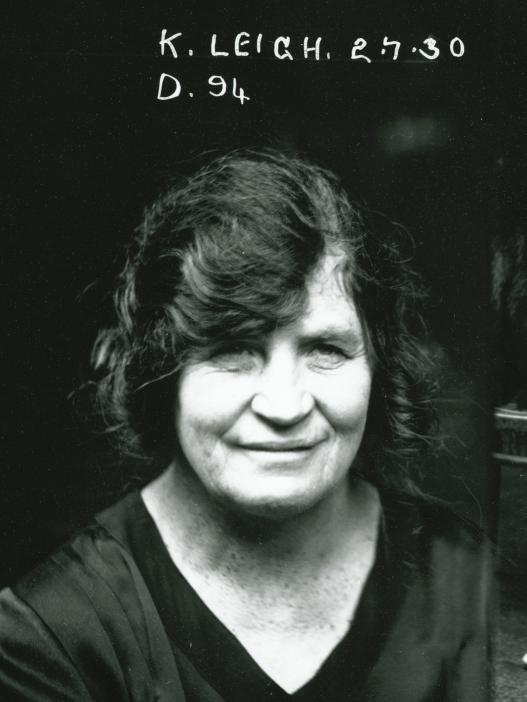

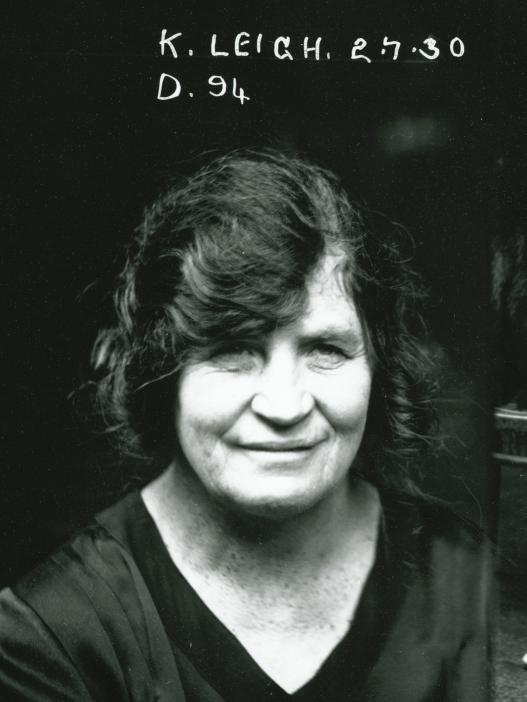

He was a notorious safe-breaker who committed Australia's first robbery with a getaway car. She was a brothel keeper and leading figure in the razor gang wars. Their wedding didn't make the social pages but it certainly made headlines.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When sly-grog queen Kate Leigh settled on a third husband his criminal antics easily rivalled her own. 'Shiner' Ryan was a talented safe-breaker who committed Australia's first robbery with a getaway car and enjoyed folk hero status despite his many arrests. This extract from Gangland North, South & West tells his story.

SOME criminals, such as Ned Kelly and even the malevolent Squizzy Taylor, manage to achieve folk hero status.

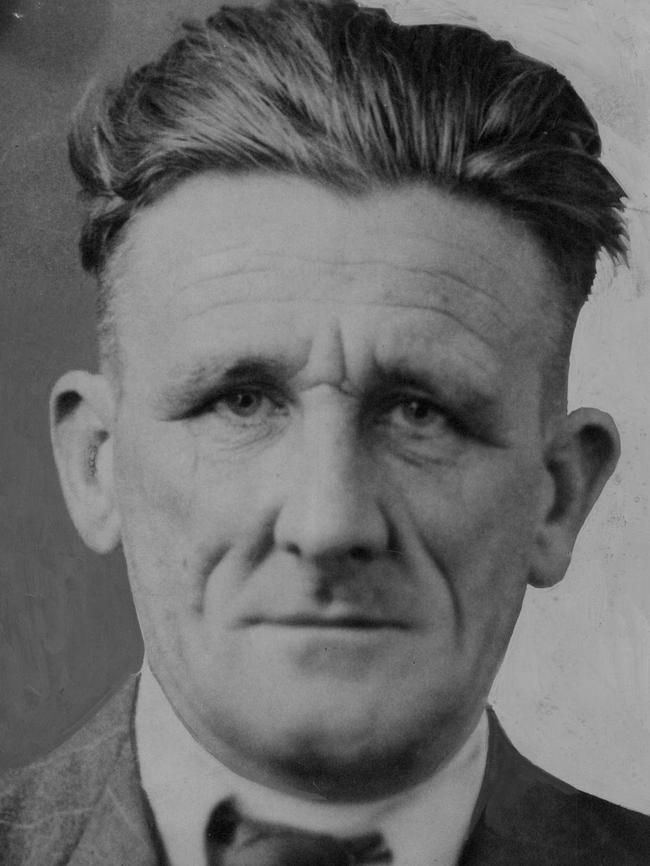

One such hero in South and Western Australia was the dark-haired, blue-eyed, 163-centimetre tall Ernest Joseph ‘Shiner’ Ryan. Born around 1885, he was a robber and safecracker, and undoubtedly South Australia’s greatest criminal of the early part of the 20th century.

Women who found him attractive thought his face glowed; less spiritually, his tattoos included a cross, an anchor, a pierced heart, the word love and a flag.

True Crime Australia: Underworld power struggle behind Macris slaying

Our criminal history: Female serial killer's decade of death

In 1902 he was convicted of larceny in Adelaide and sentenced to a birching and to be kept in a reformatory until he was 18. He escaped within a month but was recaptured at Broken Hill in New South Wales, and received three months for vagrancy. The idea of detaining him until the age of 18 must have foundered because, convicted of housebreaking at Gladstone in Queensland, he was released on a £100 bond the following year. He headed southeast and was in Sydney when, in 1904, he served three months for theft.

He went west and in Fremantle, in August 1905, he received two years and four months for stealing and receiving. This time he had been convicted with the New Zealand-born Henry Lewis, also known as James ‘Jewey’ Mackay. The 157-centimetre tall bootmaker had been in Western Australia since 1902 and had already served two sentences for theft and assaults on the police.

But Ryan never stayed in one place for long and in 1909 he, with others, was suspected of the murder of Constable William Hyde, shot and killed on 2 January at Marryatville in South Australia while investigating a series of break ins. In the previous weeks there had been a number of armed robberies in the area in which shots had been fired, and Hyde approached three men said to be acting suspiciously near the branch office of the Municipal Tramways Trust. Unfortunately he was not carrying his service revolver.

The gunman was seen to have rested his hand on a fence to shoot Hyde. A tracker was brought in but a rainstorm had wiped out the men’s trails. Two hats and black Chesterfield coats with velvet collars thought to belong to the men were found but no charges were brought.

There were also suggestions that the killers might have been members of the King Hit push which, at the time, was in the business of robbing tramcar offices. In the first 25 years of the 20th century Hyde was one of only two South Australian police officers killed on duty. The other, killed the previous year in 1908, was Constable Albert Ring, shot after he arrested a fisherman named Joe Coleman for drunkenness at Glenelg.

In March 1909, two months after the shooting of Hyde, Ryan went to prison for three months in Sydney on an idle and disorderly charge.

He tried to escape and consequently received a sentence of three years. Then, after yet another conviction while being moved from Adelaide to South Australia’s Gladstone Gaol to serve his sentence, Ryan jumped from a train going at speed between Hoyleton and Kybunga in South Australia. Despite a heavy fall, by the time the train had been stopped and a search commenced he was clean away. He was on the run for over a year before he was acquitted of jailbreaking on a technicality, but was promptly arrested for stealing a bicycle. Another prisoner who leapt from a train was a man named Wingella, known as Butcher’s Paddy. Convicted of the murder of another Aboriginal and sentenced to death, on the way to Fremantle he escaped near Southern Cross on 27 March 1903.

It was thought that as he was an experienced bushman he would be difficult to recapture, and so it proved. There are no reports in contemporary newspapers that he was ever retrieved. Had he arrived at Fremantle he would have been the ninth man then on death row.

It was time for Ryan to move east again and who should he meet up with in Sydney but his old friend James ‘Jewey’ Mackay, now known as ‘Jewey’ Freeman, who was living with Kate Leigh, another of the great criminals of the early twentieth century. Between them they planned the first robbery in the country involving a motor car, the theft of the payroll at the Eveleigh Street Railway Works.

The Eveleigh robbery took place on 10 June 1914, four days after Freeman had shot a watchman named Michael McHale in the face during a robbery at the Paddington post office in Oxford Street, Sydney.

On 10 June two Eveleigh employees arrived on a horse and cart at the factory, bringing the payroll, which totalled slightly more than £3300.

Ryan drove up with Freeman in the passenger seat of an old grey car. Freeman put a gun to the head of one employee, Norman Twiss, and threatened to blow his brains out.

A chest was loaded into the car and the pair drove away.

Unfortunately for Freeman and Ryan the number of their car had been taken. Even more unfortunately, they had not bothered to steal one, they had borrowed it from Arthur Tatham from Castlereagh, who had duly reported it stolen and who, when interviewed by the police, seemed to know far too much about the robbery.

The man in charge of the payroll also told the police that it seemed Twiss had almost expected the attack. Freeman was dobbed in and picked up at Strathfield railway station on the night of 16 June and charged with both the post office and payroll attacks.

This left Shiner Ryan very much on his own. He stayed in Sydney, sending his share of the loot to his friend Sam Falkiner in Melbourne, but things began to unravel. First, Falkiner decamped to Tasmania with the takings. Then Ryan, who travelled to Melbourne disguised as a woman and carrying a baby, found Falkiner had left and told a girlfriend, a Mrs Edith Kelly, about the robbery. With the sound of reward money ringing in her ears, she went to the police.

Ryan was in bed with Edith in Richardson Street, Albert Park, when the police arrived. Three hundred pounds was found in a glass jar stuffed into the chimney, but that was all that was ever recovered.

Ryan was returned to Sydney where he was charged along with Freeman, Twiss and Tatham. The quartet went on trial in September that year with mixed results. Twiss was acquitted and Tatham received a mere three months as an accessory.

Ryan’s defence was hopeless. He said the reason he had left Sydney was that he had seen a drawing in the paper of one of the robbers, which resembled him and, thinking of his criminal record, knew no one would believe him. Totally unable to explain away the money in the chimney, the evidence of Mrs Kelly and the fact he had admitted to the crime on his arrest, Ryan was right — the jury did not believe him.

Both Ryan and Freeman took their 10-year sentences well. Saying that he would make a good soldier, Freeman asked to be sent to the front. Mr Justice Sly seems to have had some admiration for the pair: “I believe you are right. Both of you are bold men apparently afraid of nothing and you would make very good soldiers. Still I cannot send you to be a soldier”.

Freeman also asked that Detective Robson be given his revolver as a souvenir. Ryan said he wanted his to go to the war effort. He later told a warder he would see the sentence out in 24 hours. The next morning he was found in bed soaked in blood. He had tried and failed to commit suicide.

Freeman’s sentence was followed immediately by his trial for shooting the watchman, McHale. He received a death sentence, immediately commuted to life imprisonment. He was released in 1939 and seems to have given up his criminal career, with one minor exception.

In May 1950 he was fined £10 for stealing a blowlamp from a shop.

He had been drinking. There is no evidence he ever saw Kate Leigh again.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

On the other hand, the next 40 years saw Ryan regularly in and out of the courts and almost as often in and out of jail. Released early from his 10 years, in June 1918 he was found not guilty of a Sydney bank raid when the clerk refused to give evidence against him and his co-accused, Gilbert Purvis and Neil Gant.

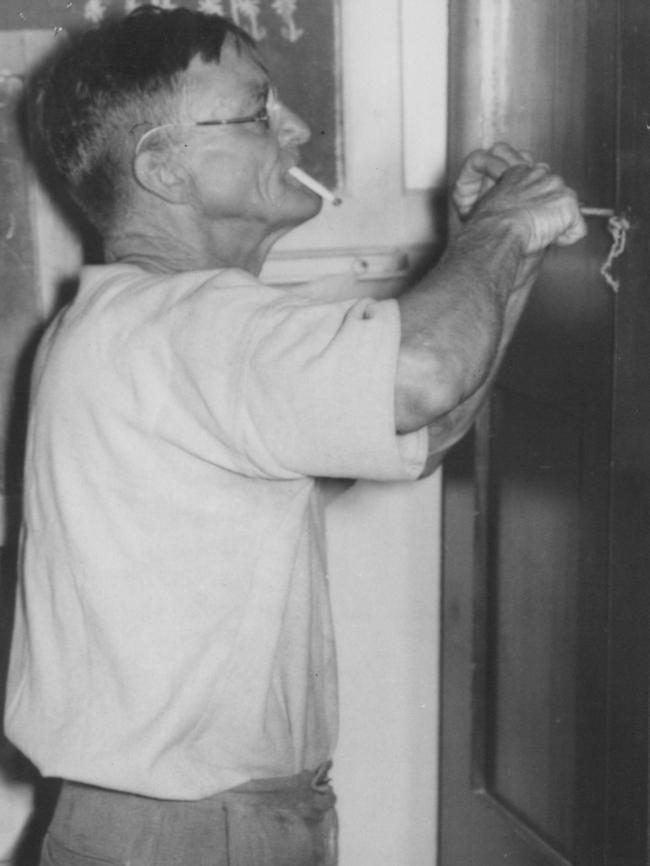

Back in South Australia Ryan soon collected eight years, this time for receiving cloth. On 12 July 1922 he managed to get out of Yatala Labour Prison with fellow prisoners Edward Watts and William Shaw. They had been locked in their cells at night but had opened the doors and climbed over iron grills and then walls. They split up but trackers were used and they were all caught within the week. The jury strongly recommended mercy but not much was on offer. Ryan received two years and the others 18 months apiece.

At his committal proceedings Ryan was said to have displayed close interest in the number and character of locks, and requested that a number of keys be produced at his trial. The police were so impressed with his escape they asked if he would explain his methods but he declined, preferring instead to sell his story, smuggled out of prison, to Smith’s Weekly to raise some money for his mother. He also made a set of skeleton keys and presented them to the Yatala governor. In July that year there were unfounded rumours he had died from complications following a bout of pleurisy.

There was no question of reformation on Ryan’s release, but sometimes his luck held. In 1928 he was acquitted in Brisbane of having stolen gelignite and a fuse with the detonator attached. The next year he was charged with a burglary in Rundle Street, Adelaide. In August that same year his conviction and a three-month sentence for failing to give a satisfactory account of himself to a police officer was quashed.

In February 1930, still in Adelaide, Ryan was charged with shop breaking, but the first jury failed to reach a verdict. This time Ryan had been able to explain that he had a torch with him because he had lost a key and was looking for it. As for the gloves, well, he always carried them to wear when he was repairing his car. The instrument that the prosecution said was for opening safes was an invention of his and, as he had taken out patent rights, while he did not feel obliged to explain what it was for he would say that it was not for dishonest purposes.

He thought the story that Constable Donald Beatty had been shot at and that a bullet had struck his police whistle was quite wrong. He was, however, convicted on a retrial and the prosecutor indicated he was considering making an application to have Ryan declared a habitual criminal. Instead, he received a twenty-eight-month sentence.

In October 1932, however, Ryan, now called Cleman, was sentenced to five years after shooting at a man who tried to stop him when he attempted to drive off without paying for petrol in the Perth suburb of Subiaco. In September 1938, together with Thomas Wood and Ernest Dawson, Ryan was charged with robbery at a store in suburban Gingin.

Unfortunately for Ryan he was suspected of being involved in more robberies and was quite prepared to shoot if he thought fit. He received three years, claiming he had been fitted up, not by the police but by the prosecution’s other witnesses.

By the outbreak of World War II Ryan was 54-years-old and had racked up sentences totalling 43 years, believed to be an Australian record.

Thirty years after the Eveleigh robbery, Shiner Ryan returned to the life of Kate Leigh.

He had been making models of ships to be raffled for the war effort and had sent them to her in Sydney. One raised £150. He began corresponding with Leigh, now the brothel-owning ‘Queen of Darlinghurst’, and in 1942 he sent her a painting he had done showing Christ outside Fremantle Gaol holding a black lamb named Shiner.

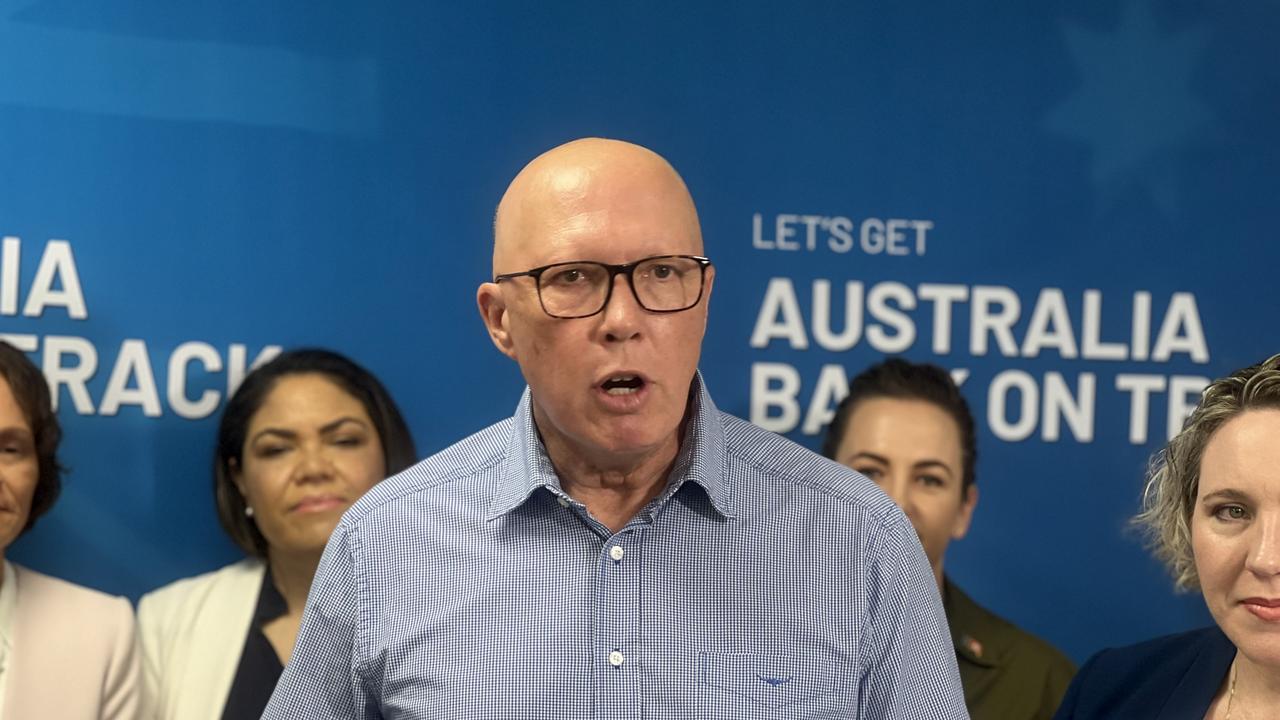

Later that year it was announced Ryan would be marrying Mrs Kate Leigh, described in the Daily News as a ‘prominent social worker’, which was one way of putting it, who had just organised a dance for the Russian Medical Aid and Comforts Committee. The wedding was scheduled to take place at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney: ‘Nothing but the best will do for the wedding.’

Unsurprisingly, since he was still in prison nothing came of the announcement, and it was not until his release in 1947 that Ryan went to Sydney, where their engagement was announced shortly after Leigh and the press met his plane. The wedding took place in Fremantle on 18 January 1950; he in a fawn double-breasted suit and green fedora and she in a delphinium blue gown with silver beads, a black veil, white gloves and nylons.

It would be pleasant to record that these two old villains found happiness, but it would not be accurate. They returned to Sydney, but Ryan pined for Western Australia. He stuck it out for three weeks and then was off. Some little time later Leigh tried to claim £3 a week in maintenance, a gesture Ryan resisted, saying he would rather go to prison where he would at least get treatment for his asthma.

In semi-retirement Ryan ran a radio repair shop in Fremantle, throwing parties for children at which he blew up condoms as balloons, repaired instruments for the Salvation Army band and provided trainers with ‘jiggers’ to improve the running of their horses.

When Ryan died on 27 June 1957 the Mayor of Fremantle, Sir Frederick Samson, was one of the pallbearers. Kate Leigh paid Ryan his due tribute. He was, she said, a brilliant man who could open any lock with a wire coathanger and his hands behind his back. There was also a little poem in the Sydney papers:

“Shiner, we cannot clasp our hands sweetheart

Thy face I cannot see

But let this token tell

I still remember thee.”

Gangland North, South & West by James Morton and Susanna Lobez is published by MUP

- This is an edited version of a story first published in May 2016

Originally published as The unholy union of sly grog queen Kate Leigh and safe-breaker Ernest ‘Shiner’ Ryan