Dennis Allen’s mum planned to kill him to put an end to his murderous rampage

The horrific torture and brutal killings committed by Richmond’s Mr Death had to stop, so his mum decided to put an end to the violence her own way. But things didn’t go to plan.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

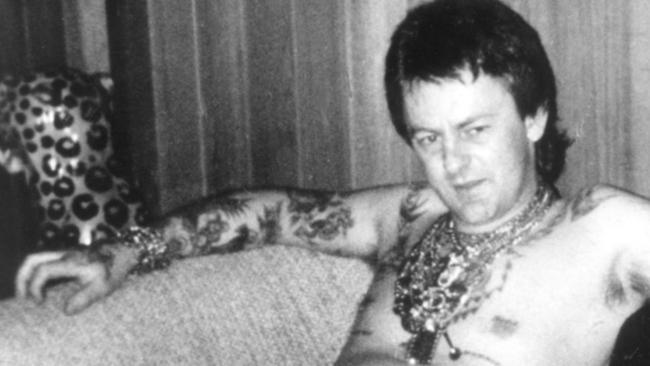

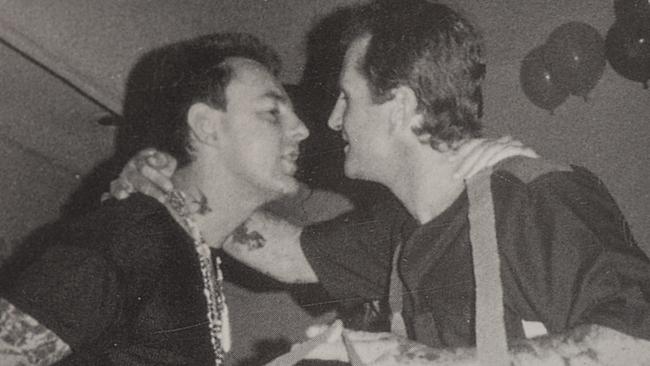

Rock star Little Stevie Wright is adrift in Melbourne and hanging out for a taste.

The Easybeats front man has a voracious appetite for smack, (heroin), but he’s far from home and his Sydney connections.

Being Australia’s number one rock star from the ‘60s doesn’t cut much ice 20 years later, and Little Stevie is scraping the barrel when he enlists the help of an addict called Billy.

The pair run into one another late at night in St Kilda, where Stevie is clocking the backstreets, desperate to score.

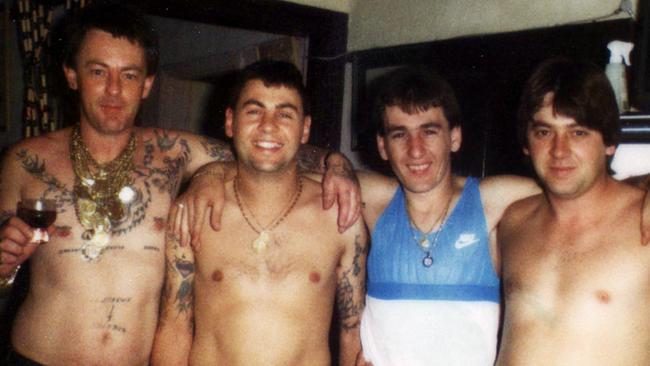

Billy knows someone, a mass murderer nicknamed Mr Death, and offers to take Stevie over to his Richmond fiefdom and introduce him. A party is in full swing when they arrive at Dennis Allen’s drug house in Stephenson Street.

Mr Death is so delighted to have the rock star at the party he tosses him a bottle of bourbon and a free bag of smack.

Before Stevie returns to Sydney he arranges for Dennis to become his regular supplier, he’s so happy with the quality of his drugs. But there’s just one problem – Billy overhears their conversation and decides to cash in.

Later, unknown to Wright, Billy phoned Dennis, saying Stevie has asked him to pick up several hundred dollars worth of heroin for him, and would settle up later. This happened another couple of times, until Dennis began to worry when the $2000 Stevie owed him was going to be paid.

Around this time Wright arrived in Melbourne and phoned Mr Death, anticipating the same warm welcome he’d received at the party. Dennis was abrupt and angry, and told him to front up at Richmond.

When he arrived Mr Death made it clear he wanted Stevie’s debt cleared before any further supply was forthcoming. The rock star was halfway through professing his ignorance of any debt when the phone rang. It was Billy.

FOR LIFE AND CRIMES PODCAST WITH ANDREW RULE

“Stevie wants me to pick up for him again, OK if I come round to collect?’ he said. “No worries. See you soon,” Dennis replied warmly.

Then he made Stevie hide in a back room, telling him to emerge with a lighter at a prearranged signal – Dennis asking Billy if he wanted a cigarette.

Billy was at the front door within minutes, and was invited in to take a seat. “Stevie wants another taste, does he? When did you speak to him?” asked Allen.

“Only a few minutes ago. Said he’d fix you up straight away.”

Then came the signal. Dennis offered Billy a cigarette and Stevie emerged, lighter in hand. Within minutes the bathroom had been prepared; the walls, ceiling and floor lined with black plastic. It was settling time for Billy, but money wasn’t what Mr Death had in mind.

For longer than he cared to remember Stevie Wright sat in another room unable to shut-out the awful cries as Dennis and his soldiers tortured Billy with lit cigarettes and axe handles.

Finally Mr Death dragged his victim back in front of Stevie, injected him with heroin and kicked him out into the street.

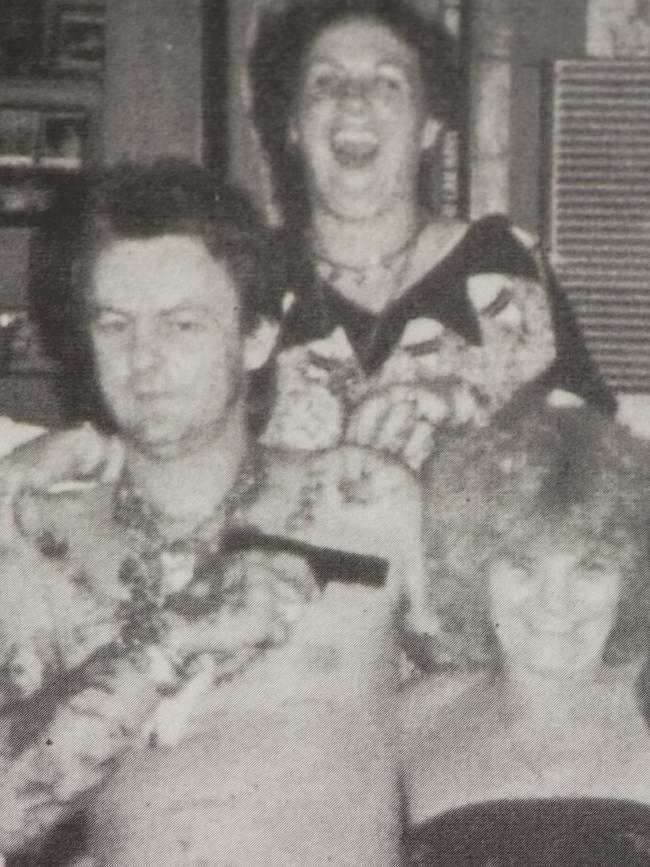

The previous occasion a victim had been dragged, kicking and screaming into the charnel house, it was only the timely intervention of Mr Death’s mother, matriarch Kath Pettingill, that prevented a savage beating escalating to murder.

Kathy came across the victim, a young boy with a machete buried in the back of his head, late one night lying half naked in the passageway between the bathroom and the lounge. Mr Death and his soldiers were enjoying a drink and a snort before resuming the business of torture.

Kathy pulled the boy to his feet, his face like raw steak, dragged him to the back gate and shoved him onto the cobblestones of the alley.

“I didn’t want him to die,” Kathy told me years later. “I saved one. Dennis and the two soldiers never did find out it was me who let him go. I got told later he’d become nearly a vegetable.

“He could still walk and that, but his mind was gone. That was it. I felt sick. To me it was disgusting. And that’s when I decided to kill my own son.”

But Dennis beat her to it.

Pettingill, matriarch of the most violent and notorious criminal family in Australian history, was settling down to watch the cricket on a gorgeous summer’s day, January 19, 1987, when the end began.

Just as the first over of the one day international between Australia and England is about to be bowled, comes a low, guttural growl as if from an animal in the throes of some terminal pain. The noise is coming from Dennis’ place.

Then it comes again. Only this time the growl builds to an awful, keening wail. Kathy is on her feet, rattling at her son’s locked front door. The sound coming from inside has descended into an incoherent, terrified gibbering.

Kathy searches frantically for the keys to her son’s house. She can’t find them and in the end does something unthinkable. She calls the cops at nearby Richmond Police Station.

By the time two plain clothes detectives arrive she has found the keys, and the three of them enter Mr Death’s house together, making for the bedroom door from behind which the wailing and moaning continues.

Dennis is lying, half naked, across the bed, his body twisted into an unnatural shape, his head lying on a bedside table. His eyes are glazed over and sightless.

“I reckon he’s had a stroke,” mutters one of the detectives.

A few hours later Kathy is sitting by her son’s twitching body in St Vincent’s Hospital in the city. Suddenly his eyes flutter open. He regards her coldly and orders her to fetch Andrew Fraser, his solicitor, a man destined for his own form of drug-addicted Hell a few years down the track.

Mr Death tells Kathy he’s bought the hospital and needs Fraser to bring the papers. Then he lapses back into sleep, only to awake an hour later and curse Kathy when she tells him of his illusion about buying the hospital.

“You f … ing idiot,” he sneers. “I only bought this f … ing room.’’

Fast forward to March 11, when Allen is taken in a wheelchair to the Melbourne Magistrates Court and charged with the murder of Wayne Stanhope, just one of a possible 13 victims who died either directly or indirectly, at his hands.

Then it’s back to the security wing at St Vincents, where doctors have diagnosed a rare disease, causing small pieces of his heart to break off and lodge in his blood steam, one inside his brain. Years of massive abuse of amphetamines mean the end is only a matter of time.

It comes on April 13, close to three months after his stroke. Dennis has been moved onto St Ann’s Ward and is hooked up to various life support systems. Kathy, as always is by his bedside; she’s been there all day.

About 6pm she notices the monitors dropping and an alarm sounds. As nurses rush in she physically prevents their access until it’s too late. But not before she’s had her chance to send him off with a mother’s unthinkable curse.

“How do you think I feel? What did you think when I wanted to kill you?”

Kathy tells me close to a decade later: “I couldn’t see any end to the murders. I had to stop them, I’d had enough. I just wanted to kill him.”

How did it all come to this? How did a happy, loving child morph into the violent psychopath who single-handedly terrorised an entire suburb?

Wind the clock back to the late 1950s when a little boy and his Dad are rabbiting in the back blocks of Carrum on the outskirts of Melbourne. Their two albino ferrets, cruel eyes glinting like rubies against their snowy white fur, are restless inside their cage, bloodlust up and raring to go.

Rabbit warrens dot the paddocks where today housing estates stretch to the horizon, transforming once open country into suburban sprawl.

The man and boy net several holes, and send the ferrets scurrying down the warrens, driving the rabbits to the surface. Every now and then one breaks through the net for cover, its ears flat with terror, its white scut bobbing frantically in flight.

The boy, Dennis, takes off in hot, breathless pursuit, his skinny legs blurring across the uneven paddock. Amazingly, almost unbelievably, he runs his quarry to ground, and then proudly conveys it back to his Dad. But first he breaks its neck.

“He were that fast, he’d catch ‘em more often than not,” Harry Allen tells me.

“He were a wild lad from the start. He’d jump forty feet off the Carrum Bridge into the Patterson River. Just to show he could do it.”

Harry isn’t really Dennis’s Dad, he’s his stepfather. And Dennis isn’t really just any wild boy. He’s a vicious mass murderer in the making. Not that Harry can see any wrong in him. When I interviewed him in the mid 1990s, the old man still spoke with touching affection of the boy who put him in hospital on more than one occasion.

“He was a good boy when he was little, very affectionate. He’d come and give you a hug. We were a close family, very close,” remembers Harry. But hugs changed to vicious beatings as Dennis grew into a violent, anti-social teenager.

“He was that big of a boy, he’d stand up and fight me. From about 14 on he stood up to me. He put me in hospital, about a fortnight I think. I was black and blue. He took to me, punched me about and kicked me.”

And then Harry’s voice softens again: “He come and seen me in hospital. He said: ‘I’m sorry I done it to you, Dad.’ I still loved him, I thought the world of him. It was more or less temper with him. He had a vile temper.”

So what brought about the change in the loving, affectionate little boy? Harry’s wife, serial bigamist Gladys, didn’t help. She’d beat Dennis with the wooden handle of a broom when he disobeyed her. Gladys, Kathy Pettingill’s mother, was hard, much harder than Harry. Maybe Dennis learned his vicious streak from her.

Harry thought it was the Frankston cops. There was the time he was down at the police station to bring Dennis home. He could hear the big, burly uniformed blokes beating the lights out of the skinny boy on the far side of a partition.

“The police was supposed to have belted him up. They give him a hiding in Frankston lockup, and the wife and I are standing on the opposite side of the wall, and we could hear Dennis screaming out. They was belting him around.”

Harry shakes his head sadly at the memory: “I think it was the police down Carrum meself. The Frankston police. They rode ‘em into the ground, Dennis and Peter. (Dennis’ younger brother.) They just had a set for them. Any trouble or that, they’d (the police) come down to my place.”

By his mid-teens Dennis was working in a panelbeating shop, building his physical strength and staying back late so he could take one of the cars for a joy-ride after his co-workers had gone home. His early convictions included three drink-driving offences committed in one 12-month period.

His first appearance before the courts was in September, 1968, at the age of 16, for indecent language, unlicensed driving and theft. The violence came later, and by the time of his first custodial sentence, in the now notorious Turana Boys’ Home, he had a fast developing reputation as a street brawler who rarely lost a fight.

It wasn’t until October, 1973, that the first full flowering of Dennis’s penchant for madness and mayhem came into bloom.

With three other men, including his brother Peter, he went on a rampage that ended in a ten-year sentence for Dennis, and 14 years for Peter.

It all began in a flat in Sandringham where the four men had gone to fulfil a $500 contract on the life of a well-known massage parlour operator; $500 for a killing, split four ways. Dennis, still in his 21st year, already placed a frighteningly low value on a human life.

The parlour operator never turned up, so Dennis, Peter and their two accomplices took it out on three girls and a man present in the flat at the time, raping the girls and pistol whipping the man.

The rampage continued for three days, and saw three men shot, one in the foot, one in the face and another, Christopher Stockley, of the Dingoes rock band, in the back. Miraculously all three survived, but then Peter engaged in a shootout with police and the mayhem was over.

They say murder is a little like infidelity – the first time is soul destroying, like the first lie told to a loved one, but it becomes easier with practise. But Dennis hadn’t yet tasted the real thing, and when he did his response was anything but cavalier.

Mr Death committed his first murder, albeit as an accomplice, in May, 1983. The victim was 22-year-old Greg Pasche, who Kathy Pettingill had adopted and treated as her own son.

She was away in Sydney on drugs business, and returned to find Dennis using electric heaters to dry a wet patch on the floor of his home in Chestnut Street, Richmond.

Dennis suddenly threw a truly terrifying fit in front of Kathy, hurling himself to the ground in a foetal position and howling like some sick animal. Pasche’s body turned up in a shallow grave in the Dandenongs, with a smashed skull and multiple stab wounds.

Kathy worked out the time frames and put two and two together. She had left Pasche with Dennis and another man, armed robber Victor Gouroff, who, according to police, Dennis murdered years later.

Her son’s bizarre hysterical fit was the clincher; Kathy remains convinced, to this day, that this was an uncharacteristic show of remorse from Mr Death, remorse that was remarkably absent from the aftermath of subsequent killings.

When he pumped several bullets into the chest of former Hell’s Angel Anton Kenny over some imagined slight, Kenny asked: “Am I going to die.”

One witness who was present, convicted murderer Peter Robertson, made a statement to police in which he claimed Mr Death replied to Kenny’s pathetic question: “Don’t be a weak c---.”

And then, when he couldn’t fit the corpse into a 40-gallon drum, Allen used a chainsaw to remove Kenny’s legs.

Helga Wagnegg, a prostitute who frequented Mr Death’s domain, was another who met a terrifyingly sordid end. She had arrived at the drug house in Stephenson Street and promptly collapsed. Earlier she had injected herself with heroin in the toilets at the nearby Cherry Tree Hotel.

When Mr Death found her lying in a passage he dragged her into the back yard and injected her in the neck with amphetamines … his personal recipe for reviving those who inconveniently overdosed in his presence.

He covered her inert body with a plank of wood, so the police helicopter would not spot her in one of its regular flights over the area.

The story is then taken up by Dennis’ nephew Jason Ryan, who was later to play a major role in the Walsh Street police massacre.

In an unconnected court case, Ryan said Mr Death had ordered him to fetch a bucket of water from the nearby Yarra River.

“Dennis tipped it down her (Helga’s) throat and then held her head in the bucket for half an hour,” Ryan recalled. Allen had wanted to give the appearance that Helga had drowned in the Yarra, where her body was found a few days later.

When an Inquest was scheduled into the cause of Helga’s death, Allen ordered his young brother Jamie to blow up the Coroner’s Court with a homemade bomb the night before. It went off prematurely and destroyed the courthouse steps … nearly finishing off Jamie at the same time.

It wasn’t just humans who suffered Mr Death’s mindless cruelty. He once pistol whipped Fatso, his Doberman dog, to near death. And when Harry Allen remonstrated with him over the incident, he beat the old man so severely he once again ended up in hospital.

MORE TRUE CRIME:

FOOTY THUGS MAY BE EXPELLED FROM MCC

WHY SILK-MILLER MURDERER COULD GET AN APPEAL

AUSTRALIA’S MOST FEARED CRIMINAL IN 1916

A special fate was reserved for the wildly expensive pet fish Mr Death purchased to populate the gold plated aquarium of which he was so proud. Money is hardly an obstacle when your drug empire is pulling in $70,000 a week, and Allen spent thousands on the fish tanks.

Nor did he think twice about forking out hundreds for each of the rare fish that swam lazily in the waters of the aquarium.

On special days he would gather together a group of soldiers before tossing a Mexican fighting fish into the water. But not before making book on which of the exotic species would be the first to be torn to pieces. Wagers regularly ran into the thousands of dollars.

For rabbits, fish, dogs and humans it was all the same. It wasn’t healthy to be around Mr Death. Not if you valued your life.

Originally published as Dennis Allen’s mum planned to kill him to put an end to his murderous rampage