Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda’s High Court appeal over Albert McColl slaying has rippled through the ages

If Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda thinks he has problems while facing trial for the murder of an NT cop, his lawyer is experiencing ‘the worst predicament that he had encountered in all his legal career’.

Indigenous Affairs

Don't miss out on the headlines from Indigenous Affairs. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s August 1934 and in the Northern Territory’s newly minted Supreme Court Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda is in the fight of his life

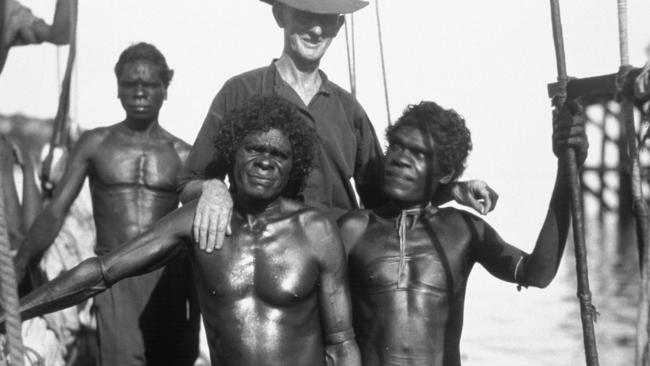

The Yolngu cultural leader had been duped into travelling to Darwin to face trial for the murder of Constable Albert McColl on Woodah Island a year earlier — and by the end of the day he will know if he is to live or die.

In Dhakiyarr’s corner in his bid to stay off death row and get back to his family in the remote East Arnhem Land outstation of Dhuruputjpi is Sydney barrister W J P Fitzgerald.

Dhakiyarr speaks no English and Fitzgerald, being unconversant in Yolngu Matha, is taking his instructions from Protector of Aborigines Cecil Cook.

But if Dhakiyarr thinks he has problems, Fitzgerald is experiencing “the worst predicament that he had encountered in all his legal career”.

A witness, Parriner, has just given evidence against his client, at the conclusion of which, judge Thomas Wells had thought it prudent to ask him “whether he did not think it proper to discuss the evidence with the accused and see whether it was correct”.

Fitzgerald agreed that it would be “desirable to take that course” and with the aid of an interpreter, asked Dhakiyarr what he made of Parriner’s story before the court heard a contradictory account from another witness, Harry.

But only later, after the jury had returned its verdict of guilty, would Fitzgerald reveal what had happened behind closed doors.

“I would like to state publicly that I had an interview with the convicted prisoner Dhakiyarr in the presence of an interpreter,” he told the court.

“I pointed out to him that he had told these two different stories and that one could not be true, I asked him to tell the interpreter which was the true story, he told him that the first story told to Parriner was the true one.

“I asked him why he told the other story, he told me that he was too much worried so he told a different story and that story was a lie.”

What Parriner had told the court was that Dhakiyarr had confessed to spearing Constable McColl after the policeman effectively kidnapped three of his wives.

Dhakiyarr was hiding in the bush, watching Constable McColl and communicating with one of the women via sign language, instructing her to move out of the way before throwing his spear.

“The policeman clutched the spear with one hand and with the other drawing his pistol, fired it three times and then spoke no more,” the story went.

“He threw his spear lest the policeman should kill him, that when they saw the police they were all very frightened, including the (women) and (children).”

But in overturning Dhakiyarr’s conviction and subsequent death sentence some months later, a somewhat bemused unanimous panel of High Court judges struggled to understand why Fitzgerald “should have conceived himself to have been in so great a predicament”.

“He had a plain duty, both to his client and to the court, to press such rational considerations as the evidence fairly gave rise to in favour of complete acquittal or conviction of manslaughter only,” the nation’s top judges said.

“No doubt he was satisfied that through (the interpreter) he obtained the uncoloured product of his client’s mind, although misgiving on this point would have been pardonable.

“But even if the result was that the correctness of Parriner’s version was conceded, it was by no means a hopeless contention of fact that the homicide should be found to amount only to manslaughter.”

The High Court ruled Fitzgerald’s actions in “openly disclosing the privileged communication of his client and acknowledging the correctness of the more serious testimony against him” was “wholly indefensible”.

“It was his paramount duty to respect the privilege attaching to the communication made to him as counsel, a duty the obligation of which was by no means weakened by the character of his client, or the moment at which he chose to make the disclosure,” the judges held.

“Our system of administering justice necessarily imposes upon those who practice advocacy duties which have no analogies and the system cannot dispense with their strict observance.”

The debacle was just one of a number of spectacular miscarriages of justice that characterised Dhakiyarr’s trial and rendered any retrial impossible, leaving a full acquittal the only option — but it was one that would echo through history.

The above quoted passage would be resurrected in another successful appeal many decades later, with Victoria’s highest court citing it as authority for its finding that another lawyer’s conduct that went “to the very foundations of the system of criminal trial” had resulted in “a substantial miscarriage of justice”.

That lawyer’s name — Nicola Gobbo, aka Lawyer X.