Farmer wants a fish: JCU helping find best looking barramundi

There are plenty of fish in the sea, and if you think Tinder is tough, spare a thought for barra being judged by a new AI program. See why farmers are loving it.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

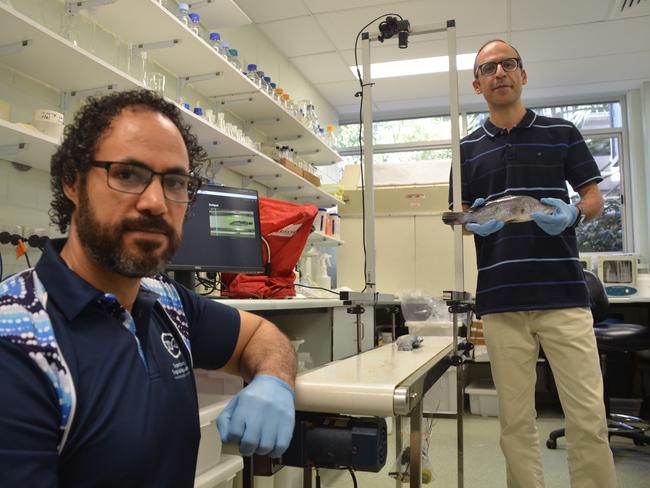

JCU researchers are developing a AI program that could help farmers detect the perfect barramundi without even getting their hands wet.

There are plenty of fish in the sea, so which barramundi go on to breed the next generation might soon be decided by an AI program.

James Cook University associate professor Mostafa Rahimi Azghadi said farm-raised barramundi often live in aquaculture systems alongside 20,000 to 60,000 other fish.

“Right now farmers are measuring maybe 100 fish in a batch to predict what sort of tonnage they have,” Dr Azghadi said.

“And of that 100 they might choose the best 10 to keep as broodstock.”

This means Aussie barra farmers are only judging about 0.5 per cent of their stock before it’s harvested.

Sensing a gap in the market, JCU researchers in Townsville began developing an algorithm to help farmers find their perfect catch.

“The selection of better broodstock is one problem farmers are trying to solve right now,” Dr Azghadi said.

“With this AI, we could scale from measuring 100 fish to 1000 and the camera will capture a lot of information usually missed.”

It will also eliminate the need for extra workers, saving farmers significant labour costs.

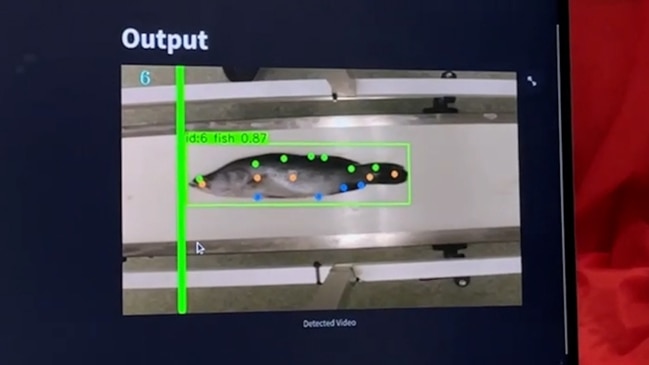

Called the Mobile Fish Landmark Detection Network (MFLD-net), the AI system was developed by PhD candidate and AI researcher Alzayat Saleh.

“It’s very hard to measure fish because it takes time and it’s all done by hand,” Mr Saleh said.

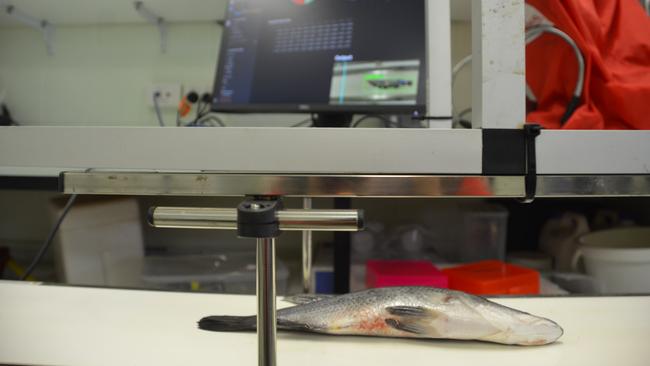

“This AI can measure the size, length, estimate the weight, measure the head-to-tail ratio and estimate the potential fillet yield as the fish passes under the camera on the conveyor belt.”

The system can measure barramundi, prawns and is being trained for groupers after a Cairns-based fishery showed interest.

Dr Azghadi said the AI can also alert farmers to incorrect colours, spots, sea lice and deformities.

“From what farmers are telling us, five per cent of farmed fish can be deformed,” Dr Azghadi said.

“If farmers can capture those fish sooner and remove them, they can save a lot of time and money, rather than raising these suboptimal fish and selling them for less at harvest.”

The addition of fillet size predictions can also increase financial certainty for farmers.

“This program helps farmers select the best animals for better progeny, but it also predicts the yields so they can say to a buyer ‘I will have this much tonnage of fish and X amount of fillet by X’,” Dr Azghadi said.

Currently all barramundi measurements are taken by hand.

To judge the condition of live fish, farmers add a sedative to the water, collect the barramundi which rise to the top and measure them before transferring the fish to recovery tanks.

It’s a time sensitive process and is considered so high stress on the fish that sedation is a must.

“It takes time to measure them and there is also human error involved, because they are just using tape measures and writing the numbers down,” Dr Azghadi said.

Dr Azghadi and Mr Saleh said the AI technology could be applied in both aquaculture and conservation.

“In the future we have an idea of measuring fish as they are pumped through a chute so they don’t ever need to be taken out of the water,” Dr Azghadi said.

Conservation agencies are also interested, according to Mr Saleh.

“This can be applied to underwater cameras to monitor fish behaviour,” Mr Saleh said.

“If a marine biologist needs to count how many fish are feeding on some sea grass for example, or to look at how coral bleaching affects fish migration and numbers, it could be helpful.”

JCU plans to begin trialling the AI with aquaculture industry partners by the end of the year.

More Coverage

Originally published as Farmer wants a fish: JCU helping find best looking barramundi