Cunningham: No more excuses for DV against Aboriginal women, girls

We need a cultural shift that says DV is never okay, and will never be accepted by society, our courts or institutions. For as long as the abuse of Aboriginal women and girls is downplayed, excused or even condoned, this crisis is will only get worse, writes Matt Cunningham.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 2005, the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory held its first ever sitting in the remote community of Yarralin in a case that would create significant controversy.

The events of that day were recorded in an essay written by the Northern Territory’s coroner, Elisabeth Armitage – who at the time was a prosecutor in the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The essay, published in the Law Society’s Balance magazine, focuses largely on the event of the court sitting in the community.

There are references to His Honour Chief Justice Brian Martin resembling Santa as he sits under a tree, and the “feathered companions” who “felt entitled to perch above and relieve themselves as they normally would”.

But a few sentences towards the end of the piece speak to a horrific ordeal for a young female victim.

“The Supreme Court sat in Yarralin to hear the plea of GJ, a 55-year-old Aboriginal traditional man and elder in that community,” she wrote.

“He pleaded guilty to assaulting his promised wife, aged 14 years, with a boomerang; and having sexual intercourse with her. He was not aware that ‘Gardia’ (white man’s law) made these acts illegal. Both acts were permitted under his view of traditional Aboriginal law.”

She went on to say: “GJ was sentenced on each count to 5 months and 19 months imprisonment respectively, making a total head sentence of 24 months, suspended after servicing one month’s imprisonment. Though the objective facts were serious (forced anal intercourse resulting in injury to the child) significant factors in mitigation were advanced by his lawyer on behalf of GJ.”

In particular, His Honour was cognisant that GJ did not know it was unlawful, under Territory law, to have sexual intercourse with a child; and that his moral culpability was low because his actions were considered ‘right’ in his culture.”

The one-month jail term given to GJ caused some outrage and was eventually appealed by the DPP, resulting in a longer sentence.

But the case is instructive about the drivers of domestic, sexual and family violence, their alarming rates in Aboriginal communities, and the attitudes of our institutions towards them.

Last week Ms Armitage delivered her report into the deaths of four Aboriginal women killed by their violent partners.

She revealed her office was aware of 87 women killed in domestic violence incidents in the Northern Territory since 2000.

Eighty-two were Aboriginal.

How do we explain this disparity? Poverty, intergenerational trauma, alcohol abuse? They are all factors.

But we should also consider the prevailing patriarchal structures that still exist in some communities.

It was not long ago that Western society was still dominated by these structures.

The push for equality for women has been hard won by fearless feminists.

The fight for Aboriginal women, however, is proving a tougher battle.

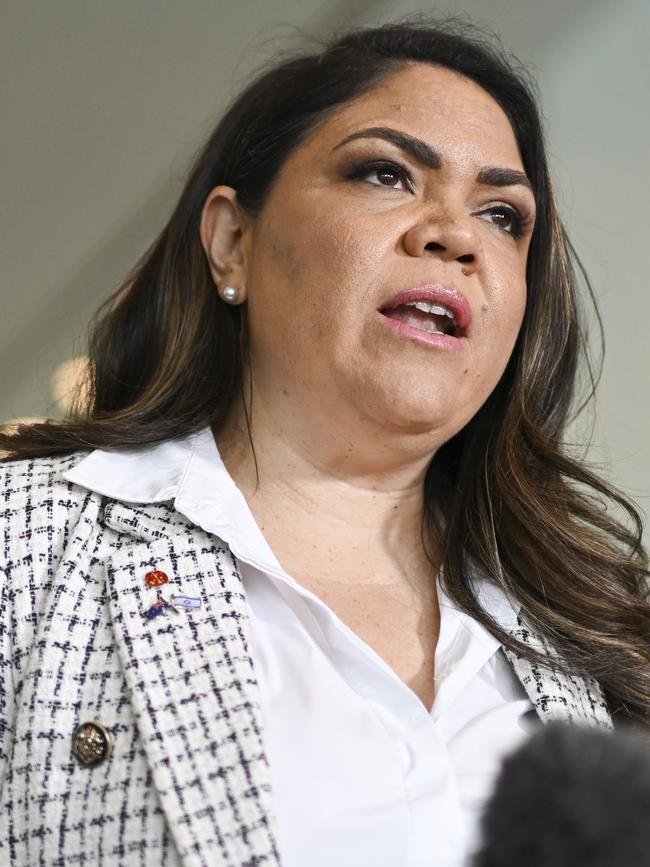

As Shadow Minister for Indigenous Australians Jacinta Nampijinpa Price said last year: “Have we had our feminist movement?” The answer is clearly no, and those at the frontline of western feminism have often gone missing in this fight.

In her report, Ms Armitage quotes Our Watch, a national peak body targeting the prevention of domestic violence against women and children.

It recommends that “to prevent violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, programs must challenge misconceptions about the violence perpetrated against them.

These misconceptions include that violence is a part of traditional Indigenous cultures.

That third-hand evidence provided by an organisation based in Melbourne fits uneasily with the first-hand evidence the coroner saw in Yarralin almost two decades ago.

There was a time when the violence suffered by Aboriginal women and girls went largely unreported.

That’s beginning to change, thanks to strong Aboriginal women who have risen to positions of national leadership.

People like Senator Price, Marion Scrymgour, Kerrynne Liddle and Malarndirri McCarthy who now sit in the Australian parliament.

There was widespread media coverage of the coroner’s report.

We’re now having the conversation, but it’s not always an honest one. While the coroner’s report addressed the issue of culture, much of the discussion that followed focused on funding.

Funding is important and that it’s clear most of our service providers are chronically underfunded.

But most of this funding is going to help women after they’ve been victims of domestic violence, or men once they’ve been perpetrators, rather than to prevent the violence in the first place.

As Senator McCarthy told MIX FM this week: “We need to look at what’s happening with the men. We have to change behaviours.”

What’s needed is a cultural shift.

One that says domestic violence is never OK, and that such behaviour will never be accepted by our society, by our courts or by any of our institutions.

For as long as the abuse of Aboriginal women and girls is downplayed, excused or even condoned, this crisis is will only get worse.