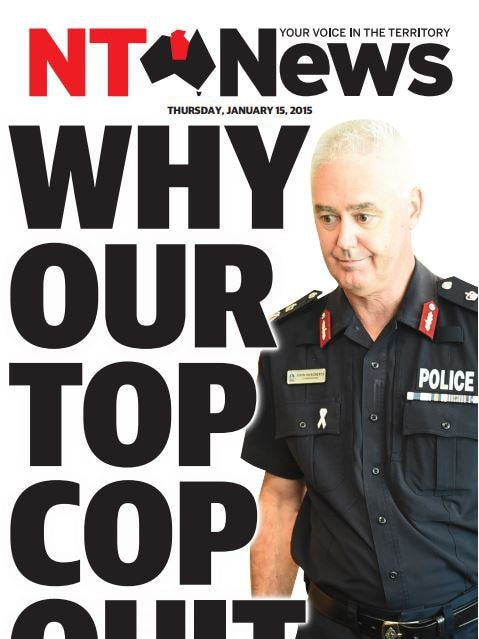

Downfall: The unlikely rise and fall of John McRoberts

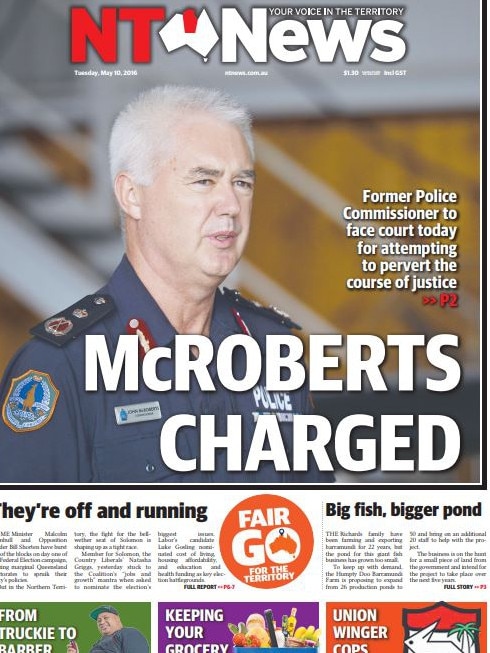

IT wasn’t the sex that landed John Ringland McRoberts in jail, it was his lies and misuse of power, as court reporter CRAIG DUNLOP writes in our special feature

Crime and Court

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime and Court. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ON a typically dreary Scottish morning in 1976, a straight-backed and boyish-faced Constable John Ringland McRoberts, fresh out of boarding school, clocked on for his first day at work with the Strathclyde Police.

On Monday afternoon, some 42 years later and half a world away, McRoberts found himself naked in the prisoners’ reception area of Holtze prison, having changed out of his checked shirt and sports jacket and been made subject to the ritual “squat-and-cough” search required of all new inmates.

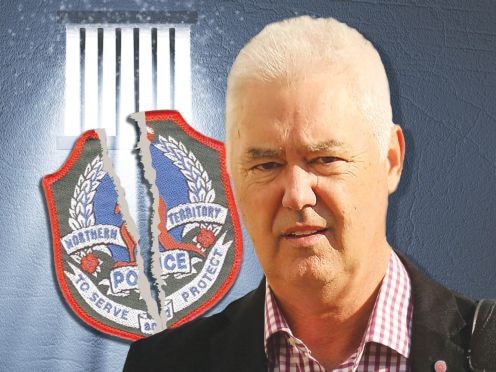

McRoberts’s spectacular “fall from grace”, as Justice Dean Mildren would describe it the next morning, was as remarkable as his rise through police ranks had been.

In the space of five years McRoberts had gone from being the NT Police Commissioner to being locked in a cell 23 hours a day for his own safety, allowed out into a common area only when all the other prisoners in his unit are in their cells.

■ ■ ■

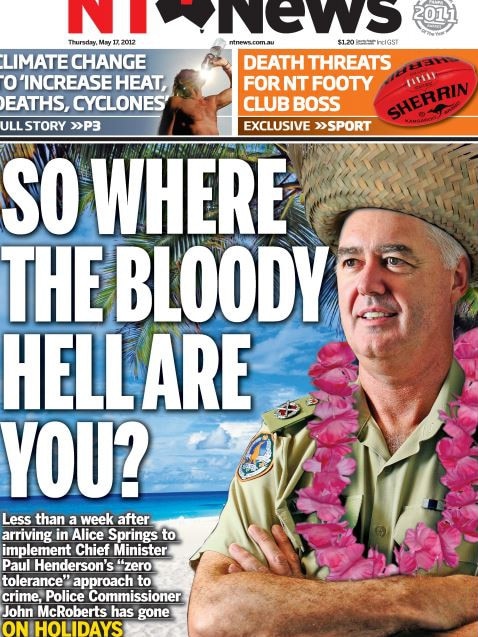

MCROBERTS’S arrival in the Territory in early 2010 was felt immediately. His supporters saw him as diligent and fair and hoped and he would shake up the NT Police force.

Among other things, the new top cop was obsessed with technology, and would go on to champion the use of facial recognition technology, body-worn cameras and social media. He would keep notes not in a standard-issue blue police diary, but on a iPad similar to the one he used as he sat in the dock throughout his trial.

McRoberts wanted to make a big impact in the Territory, where crime and social problems had gone hand-in-hand for as long as anyone could remember.

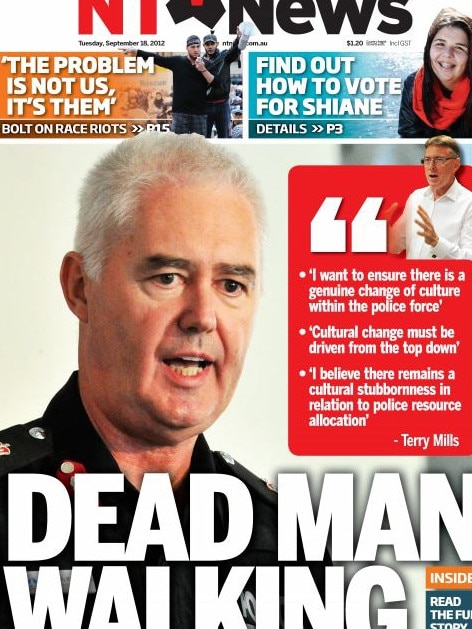

To his detractors he was “Cyclone John”, an out-of-control blow-in who promoted himself, was cosy with his political masters and made far too many captain’s calls — such as changing police uniforms from brown to blue — in a force where he was always seen by the rank-and-file as an outsider.

Despite his critics, McRoberts impressed most with his sheer commitment to the top job.

The self-described workaholic’s second wife had called time on their marriage shortly after he moved to Darwin, he having put the work he loved ahead of his home life.

Recently separated and having taken on one of the most powerful roles in the Territory, McRoberts became something of a man-about-town, mixing among those who passed for Darwin’s A-list.

It was in these circles he met Alexandra “Xana” Kamitsis, a Portuguese-Timorese suburban travel agent who would confess to him how unhappy she was in her marriage to her hardworking and well-respected husband, George.

Kamitsis, it would later emerge, had been on the take for years.

Her small suburban travel agency — now defunct — was the front for graft and fraud.

The parties Kamitsis hosted at her waterfront Bayview townhouse were famously lavish affairs where the who’s-who of Darwin’s legal, political and business community would let their collective hair down.

At one, a prominent legal figure fell, fully clothed, off the front deck into the marina before climbing out, stripping off and walking home completely nude.

Kamitsis, a decade younger than McRoberts, was at home among the Territory’s most powerful, particularly after 2012 when the CLP swept in to power and many of her close friends were parachuted in to plum jobs for the boys.

Among them, Kamitsis eyed off an out-of-his-depth former candidate turned staffer, Paul Mossman, who she lavished at first with compliments and later with corrupt kickbacks in return for him booking more than $300,000 in ministerial travel through her agency at wildly inflated prices.

McRoberts’s office too had put Kamitsis on the rotating list of travel agents they used to book executive travel.

Unknown to anyone, McRoberts and Kamitsis started a secret affair, exchanging gifts, flattery and more, although there was never any allegation of a corrupt connection between the gifts the two exchanged and the business NT Police, and McRoberts, directed towards Kamitsis.

When other travel agents undercut Kamitsis, often quoting the same fare for half the price, she would whinge to McRoberts about her “platinum” service, before agreeing, “I should learn to think cheap”.

Kamitsis in 2014, just months before she was arrested, boasted privately to McRoberts in a text message that business was up 467 per cent in 2014.

“Well done. May the success continue!” McRoberts said, not yet knowing that he was congratulating one of the most profligate white collar criminals in the Northern Territory.

Kamitsis’s bread-and-butter fraud, which would be her undoing, was her rorting of the ill-designed pensioner travel concession scheme, a government subsidy scheme that paid for the occasional free or discounted interstate flight for pensioners and carers.

Many travel agents were skimming off the top of the taxpayer subsidised pensioner travel concession scheme, but Kamitsis, it would emerge, was going in hand over fist, often rorting thousands in a single go.

It isn’t clear precisely when McRoberts and Kamitsis began their secret love affair, but it is obvious Kamitsis was immediately infatuated.

“The whole reason I fell in love with you was because my heart skipped a beat when I saw you,” she wrote in a text message in mid-2012.

“I am so unhappy in the relationship I am in … we could seat (sic) on your balcony and communicate for hours … I adored making love to you.”

Kamitsis and McRoberts’s relationship was a hot-and-cold affair.

Sometimes, she would whinge to him that he didn’t pay her enough attention.

“I want you to be my number 1 … you have not showed me the same … you have a lot of work to do … I have never loved anyone as much as you,” Kamitsis wrote in April 2014.

Other times, the two would fawn over each other, at one point spending the weekend away from Darwin in a plush hotel room in Sydney’s Double Bay, McRoberts arranging champagne and a bucket of ice for Kamitsis’s arrival.

Kamitsis, however, clearly wanted more than their semi-frequent romps, at one point inviting McRoberts to come over for a curry dinner with her close friend Marilynne Paspaley and Ms Paspaley’s partner, Garry Grbavac.

McRoberts had other plans for the weekend: a Christmas in July party and tickets to a Robbie Williams impersonator.

Afterwards, Kamitsis wrote: “It would have been perfect as its only the 4 (sic) of us, and she actually has asked about you this week. Next time.”

■ ■ ■

FAR down the ranks of NT Police, and unknown to McRoberts, the biggest fraud investigation ever conducted in the Territory had been building steam, one which aimed to both stop travel agents bleeding money from the pensioner travel concession scheme and to prosecute them for years of fraud against the Health Department.

An audit report had fingered Kamitsis as the most likely to be defrauding the scheme.

On the afternoon of May 2, 2014, McRoberts walked into a meeting blissfully unaware that what he was about to do would lead him down the path to jail.

Commander James J O’Brien read from a pre-prepared briefing about what was then known as Operation Holden, and mentioned, in passing that the main police target was Kamitsis.

McRoberts took the paper from Commander O’Brien and said, “she can’t be this stupid”.

McRoberts’s next words were the lie which snowballed into his crime.

He said he knew Kamitsis through Crime Stoppers, whose board he sat on and which she chaired, as well as “socially”.

His then assistant commissioner Reece Kershaw, who would become McRoberts’s predecessor, twigged that something might not be quite right.

Mr Kershaw would tell the Supreme Court he “did the test” to see McRoberts’s reaction and said, “well we’re probably going to lock her up”.

“That’s normally a test you do to see the reaction of that police officer, and to see if it is a friendship and they’re OK,” he said.

Kershaw told the court McRoberts responded reassuringly with the words: “if she’s going to be charged, she’s going to be charged”.

McRoberts knew any raid on Kamitsis’s office would see the fraud squad seize her phone and computers, and that those in turn would reveal his secret relationship with the woman who police were alleging was a major fraudster.

At best, it would be a bad look: the chair of Crime Stoppers being prosecuted for fraud and in a secret relationship with the Police Commissioner.

At worst, it would have been the end of his career:

McRoberts was due to start renegotiating his contract and the messages would have revealed a series of minor improprieties.

Nobody in the room that day would have cared if McRoberts had revealed was sleeping with Kamitsis or simply said he could not be involved in the investigation.

He was, after all, single, and in any case, as one senior police officer said last week, “we’re not the moral police”.

Among the messages sitting on Kamitsis’s phone were texts from her which showed she had paid for McRoberts trips to Bali and Las Vegas, and texts from him which showed he had tried to direct government business to her.

“I specifically told her to book thru (sic) U!” McRoberts wrote to Kamitsis, about tickets for a routine work trip in early 2014 his secretary, Pauline Benaim, was booking.

Justice Mildren on Monday found McRoberts’s actions over the coming months were motivated by either a desire to protect Kamitsis from prosecution, to prevent the details of their relationship coming out, or both.

THE common thread over the next few months was McRoberts’s lie by omission.

It was there in black and white, in the police code of conduct, that as soon as Commander O’Brien mentioned Kamitsis’s name McRoberts should have had nothing to do with her or the investigation in to her.

But McRoberts had a plan, loose as it was, to convince people, at least to an extent, that the criminally ill-gotten money Kamitsis and other travel agents had rorted were mere civil debts.

In an organisation which regards rank as sacrosanct, and in which he was supposed to be a pillar of integrity, few outwardly questioned him, although within a month, many would start to feel deeply uneasy with what was happening.

The man referred to as the Director of Public Prosecution’s “fraud man”, Dave Morters, had told fraud squad boss Detective Sergeant Jason Blake they had a reasonable shot at convicting Kamitsis if she still had certain key documents at her office when they raided it.

Sgt Blake is the accountant in Darwin you least want to be looking over your finances.

Mr Morters, a former Sydney cop, isn’t one to mince his words, and had effectively given Sgt Blake the green light to get a search warrant to raid Kamitsis’s Winnellie travel agency.

A month went by but then things happened quickly.

On June 4, Sgt Blake left the Supreme Court with a freshly signed search warrant, but within hours, McRoberts had called his inner circle in for a meeting where he pulled rank and vetoed the warrant, declaring it “not ready”, after he somehow finding out the raid was due to take place the next day.

A police commissioner getting involved in a search warrant is unheard of, perhaps akin to the chief executive of the education department ducking in to the local school to hold a spelling bee.

McRoberts’s trial heard he was more “hands on” than other commissioners, having taken a close interest, for example, with the security arrangements for President Barack Obama’s visit to Darwin in 2012.

But even though Operation Holden was large and complicated, unlike anything NT Police had ever done, the comparison was a weak one.

For starters, McRoberts never sent any late night text messages to Barack Obama to ask him to come over with a bottle of baby oil.

Mr Morters, in a rare display of understatement, told the Supreme Court there “might have been swear words” involved when a “disappointed” Sgt Blake found out about the warrant being cancelled.

When senior police later approached Mr Morters’s boss, Jack Karczewski, for a second opinion on the case against Kamitsis, Mr Morters warned him, ominously, that the request “seemed to be political”.

Mr Karczewski sent the file back to police with a note saying he wasn’t prepared to “second guess” his fraud man.

■ ■ ■

A FORTNIGHT later, the relationship still a secret, McRoberts ordered the Operation Holden case file to be left in his office at NAB house.

As members of McRoberts’s inner circle came and went from meetings in the following days, they noticed the file open at different points, and presumed their boss was studying it closely.

The manila folder, McRoberts thundered to Mr Kershaw, should have had evidence about travel agents other than Kamitsis in it.

“Surely after all this time we have evidence on other travel agents rather than the one,” he said.

There were 27 travel agents thought to have rorted the scheme and eight of them were flagged as “high risk”.

In what Justice Mildren found was a deliberate attempt to undermine the fraud squad’s criminal investigation McRoberts demanded to know why they were starting with Kamitsis.

“Why do we start here?” he said.

Later that week, he declared at another meeting that the fraud investigation was “more of a civil nature than a criminal nature”.

■ ■ ■

WHAT followed was McRoberts’s elaborate deception of government ministers, departmental heads and senior police.

McRoberts declared the final version of the civil debt recovery scheme, that then-assistant commissioner Mark Payne had designed at his request, as “ingenious”.

In short, the fraud squad were consigned to spending their days fiddling with Excel spreadsheets while civil lawyers sent a series of sternly-worded letters to travel agents, among them Kamitsis, asking if they would hand over the records that police could have gotten by marching in with a warrant.

The stated goal was to recover debt, and the further down the ranks from McRoberts you went, the more police you could find who were unhappy the Force had been co-opted into being the Health Department’s debt collectors.

Sgt Blake was blunt, and in an email to the task force said “ … this is an alleged crime and should be treated accordingly”.

The blowback was extraordinary, and Sgt Blake was called into then acting assistant commissioner David Proctor’s office and told to make a series of grovelling apologies for the “miscommunication” in which he had questioned McRoberts’s “ingenious” plan.

McRoberts, Justice Mildren found, had by then repeatedly and often subtly lobbied for his civil scheme to take the place of criminal investigation.

There was no smoking gun, but rather, a course of conduct that involved a comment here, a meeting scheduled there, and a consistent pattern of moving the investigation away from Kamitsis.

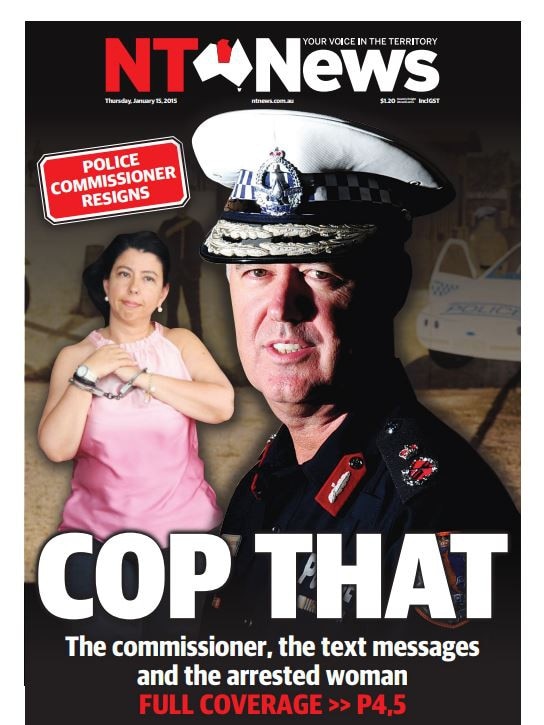

But by November 2014, Kamitsis had run out of chances.

The interagency task force McRoberts had lobbied for had gotten nothing back from their sternly worded letters other than hollow promises from her lawyer that she needed more time to get the information they had asked for.

When the call came that the bureaucrats on McRoberts’s task force had run out of patience, McRoberts was out of the Territory, on a junket to England about one of his pet projects, body worn cameras.

Back home, his other pet project, the protection of his secret lover, was about to unravel.

Sgt Blake and his new boss, Detective Senior Sergeant Clint Sims had a search warrant in hand but knew McRoberts was due back at work on Monday.

When they arrived at Latitude Travel, ABC and Channel 9 cameras were waiting after a tip off from the police spin unit.

McRoberts, Kamitsis and his supporters still squirm at the sight of Kamitsis in handcuffs being shoved into the back of a paddy wagon.

Within minutes, Sgt Blake spotted in the back office the first hint that McRoberts was something more than a social acquaintance of Kamitsis’s: travel documents showing the two had stayed together on a trip to Bali.

But it was from Kamitsis’s iPhone that the most damning evidence of McRoberts’s crime came out.

Kamitsis’s emails and text messages would prove key to the successful prosecution of her, her close friend and corrupt ministerial staffer Paul Mossman, and McRoberts.

That weekend was panic stations for senior police, as news filtered through about what Sgt Blake and Sen Sgt Sims had found.

When Kershaw fronted McRoberts about the Kamitsis lie, McRoberts turned pale and rocked back in his chair.

“It’s not true, it’s not true,” McRoberts said.

McRoberts would have a similar reaction nearly three years later when Justice Mildren remanded him in custody, and referred to his as “the prisoner”.

Six months earlier McRoberts had stood in Cavenagh St outside the Darwin Local Court, having just been committed to trial.

He spoke quietly to reporters, concerned a microphone on a distant TV camera might pick up his conversation. “I made a mistake, I fully admit that, I had an affair with a married woman, but that’s all,” he said.

It was the closest he ever came to explaining his actions in 2014, having never taken the stand in his trial, as was his right.

McRoberts will on Monday find out if he will be granted bail.

In the meantime, he has 23 hours a day alone in a cell to figure out that it wasn’t the sex that landed him in jail, it was the lies and the power.