Boxing Day Tsunami: Adelaide journalist Jessica Adamson recalls Indonesia disaster 20 years later

It was an event so terrible and enormous that it’s still burned into our minds 20 years later, writes Jessica Adamson.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It seems ridiculous, but I’d never heard of a tsunami. It wasn’t a word I’d ever had to say, until Boxing Day, 2004.

The word is now forever tattooed in my mind.

So too are the sounds, the smells and the deep sadness we witnessed in Banda Aceh, 20 years ago next month.

It’s impossible to believe it’s been two decades since that 9.1 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Sumatra, 31 miles below the ocean floor.

More than 230,000 men, women and children lost their lives, most of them in Aceh where cameraman Rob Brown, ACS, and I were sent 48 hours later.

As is often the way in the news business, we left in a hurry and arrived before any major aid organisations. Nothing could have prepared us for what we saw.

The level of destruction was difficult to process. Giant boats, picked up by the 100-foot high waves and dumped in the middle of the city.

Twisted metal, roofs, trucks and timber lay together in enormous piles as the water receded.

And the bodies of Aceh’s people were everywhere. In cars, playgrounds, by the roadside and in the trees.

The force of the water had taken their clothes. Countless fishermen never returned from sea.

It was a human tragedy on an unimaginable scale.

The survivors were stunned and frightened. There were several aftershocks that sent the locals running to the mountains. We saw the fear in their eyes.

Our job was to tell Australians that they, and their country, needed help.

There was little communication, even with satellite phones, so getting pictures out was a daily challenge.

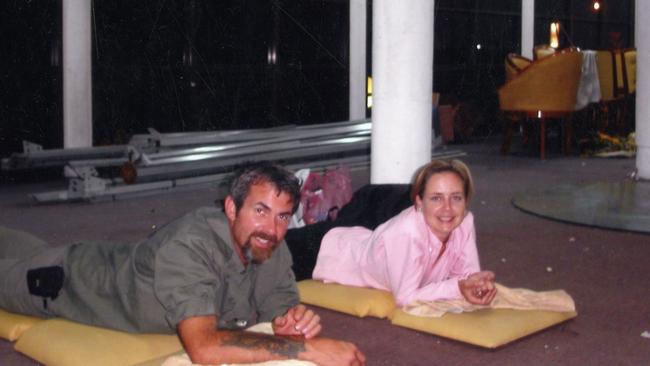

We, along with the rest of the world’s media, slept on the floor of the Governor’s residence, one of the few buildings left standing until a local family took us into their home.

The survivors had lost so much but they were so stoic and kind.

The view from the air was breathtaking, a city virtually wiped from the map.

We flew hundreds of kilometres down the coast with the US military in a search for survivors.

At every village, the people were injured and traumatised, asking why help had taken so long to arrive.

We took the sickest onboard but had to leave so many behind.

When we landed on the Abraham Lincoln, the world’s biggest aircraft carrier, to refuel we realised just how enormous the worldwide response was.

I’ve never been so proud to be an Australian than when our people began to arrive.

The Australian army began purifying the water – the city’s rivers were clogged with bodies and debris, adding to the risk of disease outbreaks.

Our soldiers drank it to show the frightened locals it was safe again. From South Australia we sent some of our best.

Doctor Bill Griggs, well known to us all from the Royal Adelaide Hospital’s Emergency Department, was dispatched as part of an RAAF Aeromedical evacuation team.

A team known as Task Force Echo included emergency physicians and nurses, paramedics, surgeons, infectious disease experts and later, microbiologists.

Reflecting on this anniversary has been an emotional time for many who played their part in Aceh.

Cameraman Rob and I had talked about going back, to reconnect with a little boy we met called Zulfahami.

He was flown to one of the hospitals by helicopter, a wristband identifying him only as number 89.

Under anaesthetic, he told an Australian trauma doctor his story.

When the water surged to shore, Zulfahami ran to tell his parents.

His mother had recently given birth and wasn’t well. They told him to run to the mountains promising they would follow, but they never came.

A little boy cruelly orphaned by Mother Nature.

With the help of a local interpreter, we discovered his elderly grandmother may have survived in a local village.

We convinced the US military to help us find her, joining one of their aerial search missions.

On my digital camera, a photo of Zulfahami from the hospital to show the villagers, in the hope of recognition.

And against the odds, we did find her. She’d never seen a helicopter before but within minutes she was on it.

We reunited her with Zulfahami at the hospital that night and as she held him tight, he let his tears flow for the first time. “Mummy died, Daddy died”, he said.

Last year I reconnected with those who know Zulfahami to find he is well and happy, still living with his grandmother and an uncle who also survived the disaster.

He’s in his 20’s now, starting a new family of his own.

A dinner, to mark the tsunami anniversary, is planned for next month – a gathering of the South Australians who travelled to Aceh.

There’ll be one empty seat, saved for Rob Brown, my wingman and dear friend, who sadly passed away from cancer earlier this year.

His absence makes next month’s anniversary especially poignant.

One day I will return to Aceh, for both of us.

Doctor Bill Griggs, AM, ASM, RAAF Aeromedical Evacuation Specialist

The devastation visible from our RAAF C130 Hercules as we flew into Banda was extreme - water still a long way inland, many buildings badly damaged, and others completely gone.

We were the first foreign aid aircraft to arrive after the tsunami.

I vividly recall those first few hours on the ground, massive destruction, stunned and injured people, bodies everywhere. And the smell.

We met with the Governor who asked for help with healthcare, food, water, fuel, security and just about everything.

I wrote a report that night for Canberra requesting lots of aid. It was all actioned, and resources began to flow.

More Australians, military and civilian, plus other nationalities arrived, repairing and running hospitals and other facilities, providing food, drinking water, shelter, and so much more.

On my second day the senior Indonesian doctor asked me if I would run a multi-national triage facility at Banda Airport.

My CO agreed. We managed patients brought in by military helicopters from surrounding regions as well as outbound Medevacs to make more room in the local hospitals.

Eventually we had Indonesian civilians and military, US Navy, Marines and NGOs, plus medical teams from China, Spain, Germany and France all working together.

It was relentless work.

I remember one six-day period where I got about two hours sleep a night, dealing with many challenges, including a 737 hitting a water buffalo and crashing on landing about 50m from us, a low flying helicopter blowing our triage tent away, and telling US Secretary of State Colin Powell that it would help if he could take his plane away as our C130 Medevac aircraft could not get flight clearance while his aircraft was on the ground.

To his credit he understood, and his aircraft was airborne ten minutes later.

Shortly after that our C130 was on its way.

There is so much more, but in the end, it boils down to being so proud of the people I had the privilege of working with.

Physically and emotionally, these were tough days for everyone. But despite the inevitable extra scars on our souls, these days were also some of the most rewarding.

Debbie Harrop, Rescue paramedic, Special Operations Team, SA Ambulance Service

We’d seen it all on TV and the pictures in the paper but actually seeing it firsthand was way worse than what you actually saw in the media.

The smell and the humidity, I won’t forget that.

We all pitched in. We had about 10 tonnes of gear, we were finding where to put everything, helping get the hospital set up, helping the nurses establish better wards, getting sicker patients into another area and then helping do the ward rounds and do the theatre list for when they started doing theatre.

For the first few days I was with our team leader Hugh Grantham a lot.

He was going out networking with other agencies who were landing from everywhere and going to the World Health Organisation meetings, that’s where you found out who was there and what capabilities other aid agencies had.

A lot of patients had aspiration pneumonia who needed oxygen and oxygen was very scarce.

With Hugh’s networking he managed to get some oxygen concentrates from the Swiss Government.

The aftershocks were a bit unnerving, but you got used to them.

We had an escape plan because we were staying upstairs and had an emergency bag packed in case we needed to evacuate.

It was a privilege to be with the 23 that we had in our team.

Everyone worked so hard, we treated quite a few patients, and I think it made a big difference to them and their families.

One of the big take homes from me was just don’t take anything for granted. You realise that when you see something on that scale.

Dave Tingey – Clinical Team Leader, Special Operations Team, SA Ambulance Service

We arrived in a RAAF C-130 with our 10 tonnes of equipment.

One of the first things we saw was the mass graves that had been created, they were alongside the road between the airport and the city.

As we were driving into the city it was clear that there were literally kilometres of dirt that had been dug up on the side of the road to bury the bodies.

There were dump trucks with bodies wrapped up in linen. There was enormous devastation of buildings, roads and other infrastructure.

I remember other scenes of mass bodies floating in the creeks and rivers going

through Banda Aceh, which over time were being cleaned up.

Even when we left the disaster, rescue crews were still digging through the mud and rubble looking for bodies.

The smell is one of the things that occasionally trigger a memory - suddenly you’ll smell something and it will just take you back there.

We were aware about the potential risks. The political situation in Banda Aceh was one of conflict, at night you could often hear gunfire.

On our first night we were very rapidly woken up. There’d been some fighting and

one of the defence units brought in two members who’d been shot.

One of them was deceased and there was nothing we could do, the other one needed surgery. It was a bit confronting given that we’d only just arrived.

We had a stream of surgical patients that were coming in with everything from broken limbs to very nasty soft tissue injuries, cuts and massive wounds to their legs, arms and heads which were quite often badly infected.

We set up a high dependency unit of sorts where we not only looked after the surgical patients after operations but those who came in with chest infections, pneumonia or other illnesses.

We also started employing local people to cook food for the patients as food became available.

The survivors didn’t have any families so there was no one to look after them.

There’s so much that was sad but there was also so much about it that was incredibly rewarding, both personally and professionally. Some of the things that I learnt and experienced there have sort of carried me through to the role that I’ve got now.

Rob Atkinson AM – Orthopaedic surgeon

We ended up in a small private hospital still standing, just, at the edge of the tsunami’s reach.

We stacked ration boxes up to shore up the roof and had bets on the size of earthquake aftershocks.

My first case, in the middle of the night, was a gunshot wound in a soldier as there was an insurgency

The work was debridement of dirty wounds, delayed primary closure, and finally split skin grafts.

The patients who survived had been triaged by death in a dirty washing machine.

We worked with two local orthopedic trainees, cognisant that it was their place and culture and we there to help.

We all worked together and hard, having a half day off to see the death and destruction around with bodies at side of the road awaiting pickup.

Unbelievable the force of Nature. We are not here by much.

More Coverage

Originally published as Boxing Day Tsunami: Adelaide journalist Jessica Adamson recalls Indonesia disaster 20 years later