What terrifies Aussies about the idea of buying an electric vehicle

Electric vehicle sales have surged in recent years as more Aussies ditch petrol cars. But those on the fence have one major concern.

Motoring News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Motoring News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Electric vehicles have soared in popularity over recent years and a large chunk of motorists are considering making the leap from petrol cars – but there’s a major sticking point.

Not too long ago, seeing an EV on the road was a rare occurrence given prohibitive purchase prices, limited options and minimal public charging infrastructure.

In 2020, EV sales in Australia comprised less than one per cent of the new car market in 2020, but last year some 87,000 were sold, boosting market share to 7.2 per cent.

In the first three months of 2024, 8.3 per cent of brand-new vehicles driven out of dealership yards were electric.

But research into the concerns of those in the market for a new car who are hesitant about going electric reveal there are some major barriers.

Prices have come down, a host of new players have entered the Australian market, bringing more choice, and major public and private investments have seen the rapid rollout of public charging infrastructure.

But one major worry remains – how long an EV’s battery will last before an expensive and cumbersome replacement is needed?

Dead in a decade?

The battery is the most expensive part of an EV, accounting for anywhere between half and 70 per cent of its cost, depending on the make.

Criticism of EVs on social media and in forums tends to centre on the belief that an EV battery will die after about 10 years. It’s unclear where this assertion originated, given there’s no reliable data or research to support the timeline.

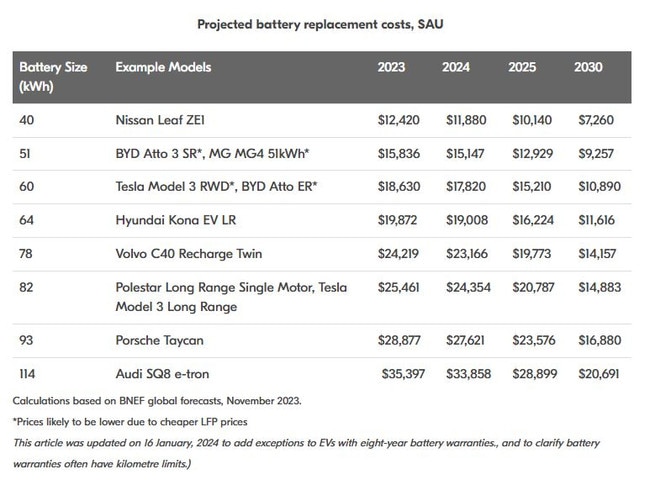

But given the hefty cost of replacing a battery, which can run between $10,000 and $20,000 or more, uncertainty about the longevity of a vehicle is a major concern for would-be buyers.

According to the Electric Vehicle Council (EVC), the average EV battery will have a shelf life of about 15 years – but that doesn’t mean it’ll be obsolete after then.

“After around 15 years the battery will still function but may only have around 75 per cent of its original capacity, meaning 75 per cent of the original driving range,” it said.

On top of that, there are likely other “general components” that will need to be replaced or refurbished at that point in time, but that’s no different to a standard petrol vehicle.

“The exciting thing about EV batteries is that even after 15 years of use in a vehicle, they can be removed and find a ‘second-life’ powering homes, buildings and the grid. This is because these batteries will still hold significant amounts of energy – enough to power several houses.

“It also means the EV owner will be able to sell these used EV batteries for use in other applications, helping to reduce the cost of a new battery for their EV, or the purchase of a new EV.”

The EVC said those repurposed batteries are expected to last another decade or so, “after which they can be largely recycled”.

A study by US tech start-up Recurrent of 15,000 EVs sold between 2011 and 2023 showed the need to replace a battery was “a rare occurrence”.

“Indeed, just 1.5 per cent of EVs have required a new battery,” it found. “Most of the batteries replaced occurred on EV models predating 2015. Among the most frequent are the Tesla Model S and Nissan Leaf.”

The majority of EV producers offer a battery warranty of eight years or 160,000 kilometre, whichever comes first.

As Recurrent pointed out, when it comes to precisely how long a battery is likely to last, “the honest answer is that we don’t know”.

“By and large, electric cars have not been around long enough for us to see how quickly they degrade and what their end of life looks like. The best we can do is observe the apparent degradation in those cars on the road.

“So far, it seems that EV batteries have much longer lifespans than anyone imagined, since very few of them have been replaced, even once the … warranty period ends. Looking just at models from 2015 and earlier, only 13% of drivers have reported a battery replacement.

“Not bad considering how far technology has come in almost 14 years.”

Newer EVs produced from 2016 and onward had a battery replacement rate of less than one per cent, it said.

Real-life test results

EV enthusiast and content creator Bjørn Nyland put popular claims about battery degradation to the test by examining the cars of real-life motorists in Norway.

Motoring publication WhichCar reported on his findings.

Among them, a 2013 Tesla Model S P85 only lost 12 per cent of its battery capacity after seven years of operation, during which time it travelled 270,000 kilometres and was charged about 1000 times.

Another Tesla, a 2019 Model 3 with long range functionality, degraded by about eight per cent after being driven 165,000 in three years.

And interestingly, a 2012 Nissan Leaf, which at the time come with far less sophisticated battery technology, lost just 24 per cent of its capacity after nine years ad some 105,000 kilometres of travel.

Where to charge?

In recent times, one of the biggest barriers to a consumer choosing an EV was what experts dubbed “range anxiety”.

That is, the ability to get from point A to B and have access to a public charging station on a long drive was limited by Australia’s slow rollout of infrastructure.

Last year, the number of charging sites increased by a staggering 93 per cent, analysis by Next System showed. EV drivers now have access to more than 2000 charging stations, it’s estimated.

However, Kai Li Lim from The University of Queensland said the boom in EV popularity has replaced ‘range anxiety’ with ‘charge anxiety’, or uncertainty about whether chargers will be available or functional when needed.

“The reliability of the network of chargers is no longer a potential problem on the horizon,” Dr Lim wrote in analysis for The Conversation. “It’s now an urgent matter.”

“In the United States, the world’s second-largest electric vehicle market, up to 20 per cent of charging attempts fail. The most common cause is charging equipment malfunctions.”

There are early signs Australia could face similar issues, with the charging industry here lacking standardisation and prone to fragmentation, he said.

“Electric vehicle users must deal with variations in plug types, payment options, communication protocols between chargers, and charging speeds offered by different manufacturers.

“Early market instability may mean companies are taken over or go out of business, possibly leaving stranded assets.

“Another issue is charger ownership and maintenance responsibilities. If a business pays for an electric vehicle charging company to install a charger, it’s not always clear who’s responsible when it breaks.

“Clear terms of ownership and maintenance, including who bears the cost of repairs or replacements, are needed.”

A cohesive approach to charging infrastructure will “pave the way” to reliability, he said.

“Australia needs charging infrastructure that is robust, reliable and ready for electric mobility. It’s a collective responsibility of industry stakeholders and government bodies. As we speed up our efforts to get this right, we can finally put an end to range anxiety and its successor, charging anxiety.”

A future problem looms

Research by the University of Technology Sydney last year suggested about 30,000 tonnes of EV batteries will reach the end of their use by the end of the decade.

By 2040, the projected figure is set to surge to 360,000 tonnes, posing a hefty challenge when it comes to recycling, preventing fires from mishandling, and limiting the risk of hazardous contamination.

As it stands, small lithium batteries such as those found in mobile phones regularly cause fires within landfill. Used EV batteries could exacerbate the issue on a grand scale.

At present, recycling EV batteries is still an emerging field, but the CSIRO has estimated that a circular economy – where finite components are stripped and reused – is potentially worth tens of billions of dollars.

What appeals to Aussies

When it comes to interest in transitioning to electric, the AADA report found the lower running costs appealed strongly to 54 per cent of prospective purchasers.

And with good reason – all things equal, EVs are about 70 per cent cheaper to run than a fuel car, while servicing and maintenance savings sit at about 40 per cent, according to Transport for NSW.

For example, Adept Economics calculated the cost of driving from Coolangatta on the Queensland-New South Wales border to Port Douglas, an hour up the road from Cairns in the state’s Far North.

Dozens of public charging locations along the 1800 kilometre stretch have been installed as part of the State Government’s so-called ‘Electric Super Highway’.

Operated by third parties, those stations charge about 30 centres per kilowatt hour, meaning the cost of driving an EV equates to roughly $4.50 per 100 kilometres travelled.

A comparable trip with a traditional fuel vehicle might require 7.5 litres of fuel per 100 kilometres driven, coming out to roughly $7.50 per 100 kilometres.

More options than ever

Tesla has long dominated the EV market in Australia, thanks in large part to the fact the brand had few serious challengers here.

Analysis by motoring group NRMA revealed that the playing field evened dramatically last year.

“While Tesla remained the market leader in EVs for 2023, electric cars from Chinese brands BYD and MG are becoming a more common sight on the road,” it said in a report.

“The BYD Atto 3 was the clear third best-selling EV in 2023 – largely due to availability. Worldwide, BYD beat Tesla in EV sales in 2023, showing that it means business in the electrification of transport.

“Just over 11,000 of the compact electric SUV were sold in Australia last year, and with the BYD Dolphin hatchback and BYD Seal sedan also now available expect to see more of these come end 2024.”

Formerly British brand MG, now a Chinese-owned company, is also “making a moderate impact on the EV market” with its MG4 and MG ZS models.

“Meanwhile, Volvo continues its mission to become a purely all-electric car company in Australia,” the report continued.

“In 2023 more than a third of its vehicles sold were all-electric – 35 per cent to be precise – thanks to its XC40 Pure Recharge and the C40 small SUV. With the EX30, Volvo’s EV with the smallest carbon footprint to date, on the way, Volvo says it is on track to be all EV by 2026.”

Originally published as What terrifies Aussies about the idea of buying an electric vehicle