STANDING still and staring at a rock fall, we all search for the elusive black-footed rock wallabies.

“They’re always there, you’ve just got to spot them,” says our tour guide Clive, from Emu Run Experience.

“Look for the slightest movement. Once you see one, you see plenty. But if we can’t find them, I’ve got a special call for them to make them come out.”

When none appear within the next few minutes, the silence is suddenly broken with a high-pitched, “Hey rock wallabies, come out”.

As the group laughs, one member spots movement in a crevice in between a slab of granite and a small eucalypt — lo and behold, the first wallaby appears.

We’re standing at Simpsons Gap, 18km from the heart of Alice Springs, and the first stop on a day trip through the West MacDonnell Ranges. The range is 644km long and takes up almost four million hectares.

Stumbled on by European settler John McDouall Stuart in 1860, they are named after Sir Richard MacDonnell, Governor of South Australia at the time.

But the history and culture of these mountains began long before European settlement, as Clive explains when we stop at the Ochre Pits.

Telling what he can of the ceremony stories of the Arrernte people (Clive is a whitefella who has been told only some of the traditions), he explains how the different colours of the rock create different paints.

Some are only worn for men’s ceremonies, such as when a boy becomes a man and wears yellow paint all over his body for days.

Others are only for women’s ceremonies, but Clive has few stories about these.

One thing he can tell us is how important the ochre is to the local indigenous people, and that we, being a group of tourists, can’t take or even touch it.

There are massive fines for those who do and Clive keeps a keen eye on us as we wander along the pit walls, admiring the change in colour from the deep orange reds to the yellows and even whites.

The rock walls rise out of a riverbed which, at first glance, looks as if it hasn’t seen water for decades, but on closer inspection displays evidence of life.

The river gums can’t survive without water, Clive says, so if we were stuck here we could dig just half a metre into the ground and we’d find it.

Looking at the sky, he warns us to be quick with our photos as it appears a storm could be rolling in, and the riverbeds can flood quickly and dangerously. There have been stories here of people camping in the riverbed and falling asleep to a starry night, only to wake up an hour later to pelting rain and their 4WD floating down a flooding river.

The landscape in Central Australia is stunning and different at every turn, and was formed millions of years ago.

Then, what is now a dry, semi-arid and dusty desert was a tropical rainforest and aspects of those days remain in the ferns found in some of the hollows.

The cycad palms in Standley Chasm have grown there forever and, as we wander along a meandering trail into the chasm itself, Clive explains the different flora that appears.

“See this tree that looks like some sort of mutant?” he asks.

“It’s not, it’s a parasite. It grows from the tree and if there are more than five or six of them the host tree itself will die.” We move further in between the mountains and suddenly the chasm is in front of us.

We’re standing in a gap of about nine metres with 80m of rock face rising into the air on either side. It is spectacular.

The red of the rock, the white of the quartz veins and the blue of the sky all shine colourfully around us and, despite being in a tour group of about 10, it feels like each of us is the only one here.

***

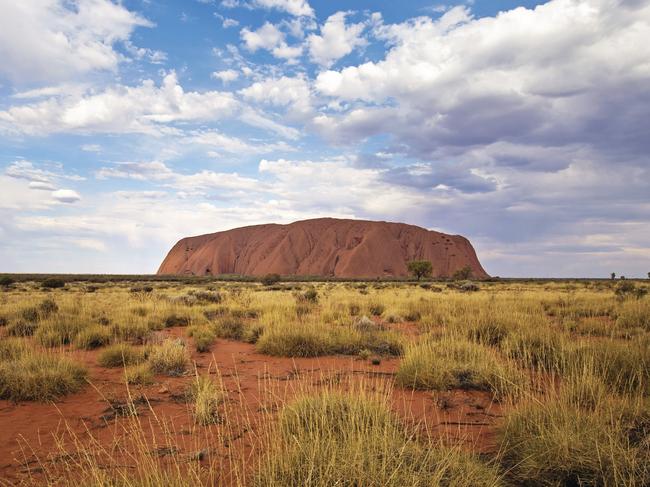

THE lines in Uluru rise vertically out of the dusty ground, a phenomenon common in Central Australia.

It shows just how ancient this land is — those lines started out horizontal, but have twisted over millions of years.

What we see now of Uluru is only the tip rising 863m into the air.

Beneath the surface about 2.5km of rock continue down, according to scientific geology surveys done before the 1980s.

Nowadays these sorts of surveys don’t happen, with the land being part of a National Park and owned by the Anangu people.

In fact, all scientific studies on the land have stopped, and Anangu culture is increasingly respected. Few people climb the rock any more and entire road patterns have been changed to fit in with local beliefs, our guide Jerry tells us.

“This road, as we travel to Kata Tjuta, used to go in a straight line directly to the rocks, but the rocks are a men’s sacred site,” he says.

“Anangu women are not even allowed to look at the rocks, so eventually the road was changed to curve so that any Anangu woman who needs to drive this road is never required to look at Kata Tjuta.”

Luckily for us those cultural laws are not enforced for tourists and the entire group is able to walk between the rocks on one of the paths.

But it’s only a quick stop, and I’m one of only a few who make it to the end of the path and back in time.

Today we’re on a deadline, having left Alice Springs at 6am and due back by 12.30am.

Within 18 hours we will have travelled more than 1000km by bus and visited one of the most iconic places in Australia.

Finally we’re at the rock itself. It is majestic, it is beautiful and it is clear why more than 250,000 people visit the park each year.

As we battle for the shady spots — the temperature here can reach up to 47C — Jerry tells us some of the stories.

“Here is where a battle took place, you can see where the spears hit the rock,” he says.

“You see Kuniya was so angry because the Liru wouldn’t tell her what had happened to her nephew.

“Eventually she took her revenge and killed one of the Liru who was rude to her, and you can see the blood that was spilt by the dying man.”

Above us, like a picture book, the patterns in the rock fit with the story.

We don’t get to hear all the tales — some are so sacred they can’t be told to tourists; others we just don’t have time to hear.

Night is coming and we travel to a spot to eat dinner and watch the colours of the rock change.

It switches from burnt orange to bright orange, before getting darker and turning almost purple.

None of these colours are its natural hue — the reds and oranges are only formed from the metals in the rock rusting.

Finally, when the shadow hits the top of the rock, we’re loaded back on our bus and begin the five-hour trip back to Alice Springs.

Most are asleep within half an hour.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Live stream: How to watch St Mary’s v Districts in Round 8

Can the champs stop the Crocs juggernaut? Southern Districts are flying high, but they likely haven’t faced an opponent of this quality yet this season. Find out how to watch the match LIVE.

How to watch every match of the 2024-25 NTFL Round 8 live

Get ready for a prime time blockbuster when unbeaten Southern Districts takes on second place St Mary’s - and it’s not the only big-time clash to savour on Saturday. Find out how to watch every match.