The cruel disease running rampant across the NT

IT’S a cruel disease that rates worse in the Top End than in war-torn Africa. Governments can’t let this shameful truth be sidelined any longer. MATT GARRICK reports

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FEDERAL Budget night, Canberra, 2018. The man in control of the nation’s moneybags, Treasurer Scott Morrison, steps up to the Lower House lectern to unfurl his department’s plan for how to distribute Australia’s wealth.

He’s got a wry smile on his face. A promise to slash taxes among the working middle class could prove popular with voters and score his battle worn Liberal colleagues another dash across the line on election day 2019.

A win for struggling families across suburban Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide could amount to a win for the struggling family of Team Coalition — a clan still bleeding from wounds caused by citizenships woes, conservative niggles and a bonking barnstormer named Barnaby.

“The Turnbull Government believes that to create a stronger economy there must be reward for effort,” Mr Morrison says. “You must not punish people for working hard and doing well. This is what underpins our plan.”

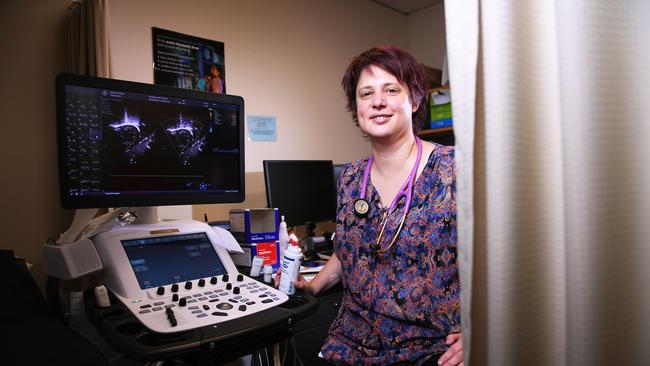

In the far north of Australia, this plan in its entirety is registered with “disappointment but not surprise”. Highly regarded paediatric cardiologist Dr Bo Remenyi — the Northern Territory’s 2018 Australian of the Year — has heard it all before.

A blatant election pitch to mainstream Australia that, by-and-large, neglects to fund further efforts to eradicate a shameful truth, a disturbing health problem, which is worsening in the remote Top End.

“It’s not different from any other budget,” she says. “Still rheumatic heart disease does not rate in the eye of politicians in Australia, and that really means it does not rate in the eye of the general public in Australia who are the voters. Perhaps rheumatic heart disease is just not sexy enough.”

She’s right. There’s nothing politically attractive about Aboriginal children forced under the knife of open heart surgery at rates worse than “any drought stricken, war-torn country in Africa”.

The Territory’s Top End continues to harbour one of the planet’s highest rates of rheumatic heart disease. It’s a scandalous fact considering the illness has been all but wiped out across the rest of the civilised world.

In the past seven years, rheumatic heart disease stats in the Top End have not improved — rather, according to Dr Remenyi, a leading expert in the field, “the rates are increasing steadily”. “There should be an urgency to address workforce issues in remote communities,” she says. “Until we address our primary health care services we’re not going to see a reduction in rheumatic fever.”

With Australia and the Territory’s purse strings continuing to tighten, where and how will Scott Morrison’s “reward for effort” be seen for those trying tirelessly to stomp out this national crisis?

■ ■ ■

THROAT infections or skin sores may seem innocent enough.

But for kids in tropical indigenous communities, they can be an onset sign of acute rheumatic fever — a condition that, if left untreated, can lead to serious, potentially fatal, damage to vital heart valves.

Laynhapuy Health manager Jeff Cook sees it far too often in East Arnhem Land. Children as young as four with symptoms of this disease triggered by squalid, unhygienic living conditions.

“It’s pretty clear that it’s overcrowding. Things like access to a shower that has hot water. Or access to a shower. Or a washing machine,” Mr Cook says. “It’s a disease of poverty.”

Rheumatic fever is born from recurring strep A bacterial infections. It’s the same bacteria which once ran rampant as a scarlet fever epidemic in the slums of Victorian era England. Snuffle nosed kids with scabs on their knees. It’s a sight common enough that plenty of sufferers get overlooked, by both the health system and their own families, to devastating consequences.

In the first three months of this year, 38 people were diagnosed with rheumatic heart disease in NT. In 2017 there were 96. Last year it killed at least four people — so far this year at least one.

Currently, 3042 Territorians are living with rheumatic heart disease, 96 per cent of who are indigenous.

Gove District Hospital’s Dr Tim Blake says diagnosing the disease properly is “complex and so easy to miss”. Serious equipment and specialist attention is often needed to definitively detect the disease — resources that are hard to come by, particularly in the bush.

“Right now we’ve got a boy on the ward who has rheumatic fever,” Dr Blake says.

“He’s now being monitored because he’s going to develop rheumatic heart disease. If he doesn’t take his medication, he is a good chance of dying in his 20s or 30s from that illness. Which is a very real possibility.”

Ensuring these sufferers take their meds is no easy task.

To ward off the symptoms and stop infection from creeping into their hearts, the patients — mostly children — are prescribed “shocking, huge” penicillin needles into the bum, every single month for a gruelling minimum 10 year regimen.

“The penicillin injection is up to two millilitres of quite a viscus, white substance that obviously is quite painful,” Mr Cook says. “It lasts for 21 to 28 days in the system. It’s a slow release thing, so it sort of sits there, you can feel it for a while. If you’re seven years old, it’s quite traumatic I would imagine.”

Senior practitioner Dr Molly Shorthouse says when she first started working in East Arnhem Land she couldn’t compute how the disease still existed at all.

“I remember the first time I moved there in 2009 thinking, ‘if this was a disease in Canberra there’d be a vaccination already. This is strep A. This isn’t a hard bug to beat’. I do believe if this had been in a population in Sydney or Canberra we’d already have that immunisation,” she says.

Dr Remenyi, too, says the continued existence of rheumatic heart disease is unacceptable.

“If a single child died of meningococcal disease or something similar, the entire country is up in arms about a young child dying, and there is demand to develop a vaccine, and to prevent this happening to any other child. No children anywhere in the world should die of a preventable disease, but certainly not in a rich country like Australia.”

■ ■ ■

HEART disease can adopt many cruel forms in the Top End. After being struck down by a powerful cardiac arrest two years ago, land rights stalwart Bakamumu Marika lay on the floor of his Yirrkala home, dormant and dying. He was 58 years old.

Family luckily alerted paramedics in time to reach the Rirratjingu clan elder and he was flown to Darwin for emergency bypass surgery. He died twice on the operating table while doctors worked.

“It was a scary experience — it was also emotional,” Mr Marika says. “It is very, very young to have a cardiac arrest. Something is wrong. We need to prevent these things happening to Yolngu people, to indigenous Australians.”The clan leader is no stranger to the tragedy of heart disease. His sister Dr Marika lost her life after complications with a pacemaker. Two of his brothers, Witiyana and Mandaka Marika, have also been forced to lie beneath the scalpel for urgent heart valve surgery — most likely a result of suffering from rheumatic heart disease symptoms since childhood.

And far too often, he has grieved with relatives over a tiny child that’s fallen victim to a disease of disadvantage.

“It’s a grief that (makes) people sometimes question themselves,” Mr Marika says. “We question, and we say, ‘what is the matter? What is wrong here?’ It can’t be just the heart disease. It makes me sad and angry.”

To try to help slow rates of rheumatic heart disease in the region, Rirratjingu Aboriginal Corporation has stumped up $63,000 for a new ultrasound system to screen for the illness at Gove District Hospital. They’ve joined forces with philanthropic charity Humpty Dumpty Foundation to do so.

Dr Tim Blake says the new machine “will help us, because it will mean we can diagnose more accurately and pick up more people with the disease, because prevention is the answer to it. Poverty is the cause, but prevention is simple”.

But why has it become the role of private industry to fork out for necessary equipment to service government-run hospitals? As a spokesman for NT Health Minister Natasha Fyles says, rheumatic heart disease is “a disease of social disadvantage and it is 100 per cent preventable”.

So why hasn’t it been prevented?

After decades of frustration watching a lack of progress, Humpty Dumpty patron Ray Martin, the acclaimed journo and television host, is livid over the stagnant state of the Top End’s disease rates.

“It doesn’t seem to change. And I don’t think it’s because of racism, I don’t think it’s because Australians don’t care. Australians care,” Mr Martin says.

It’s a complex mess of reasons, he believes. Apathy across remote communities. The tyranny of distance. He also thinks a misdirection of government spending has played a prominent role in the failure to find significant change.

“We didn’t hesitate at Malcolm (Turnbull) spending $120 million on the same-sex marriage vote that we all knew where it was going to end up. You know $120 million in the program you’re talking about now would make a huge difference,” he says.

“It seems to be a lack of direction from governments of all persuasions. Every time they’ve come through they’ve done stuff all. Prime Ministers of both persuasions (have failed). Gough (Whitlam) went out and dropped the soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hands, but what happens in terms of policy and medical priorities? We put them on the backburners and meanwhile generations of Aboriginal people die young and die in sickness and sadness.”

■ ■ ■

INDIGENOUS Health Minister Ken Wyatt is standing at Canberra Airport post-Budget, en route to Perth. He’s weary after a week of long boardroom hours.

He concedes that rheumatic fever has “not really been given the attention it should have”.“It’s something that should never have evolved or occurred … not in a first-world country,” Mr Wyatt says. Although nothing new has been specifically slated towards blotting out the disease in the 2018 Budget, he says the document does offer some signs of promise.

Half a billion dollars will hit the Territory in the new financial year for remote housing (under a model which Federal Labor claims is “not going to cut it” and “is not the solution that we need”) and $4.9 million will go towards halting the spread of crusted scabies — another trigger for rheumatic fever.

And the heart disease is on his radar. Mr Wyatt held a landmark roundtable discussion with Dr Remenyi and other experts in Darwin this year, with the end game being a road map towards a solution that’s currently being formulated. But time is ticking and resources remain scarce.

“I am looking at what additional funding I will require to make sure that we tackle this with some gusto,” Mr Wyatt says. Money which may be found in “future years of budgets”.

The minister’s heart is in the right place about the issue, says Dr Remenyi. But it isn’t enough.

“Ken is actually genuinely interested and passionate about indigenous health. Unquestionable that his motivations are clear and he has a desire to make change. But it takes more than Ken Wyatt to come up with a policy and the rest of the cabinet also have to sign up for that.”

On top of Commonwealth commitment, she says, the Territory Government urgently need to put more bread on the table.

“Right now we have more than 3000 people in the NT with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. And over 2500 of them are still needing monthly injections,” Dr Remenyi says.

“It is time for the NT Government to think about … what action plans we need to develop to ensure that we address this disease in the NT. Because in Australia, we’ve got the highest burden. It’s a disease of the Top End.”

A spokesman for Ms Fyles says Labor’s $1.1 billion spend on remote community housing was part of the government’s contribution to stomping out the scourge.

On the other side of the planet, the World Health Assembly is taking place in Switzerland this week, where Australia’s rheumatic heart disease burden will be laid bare in front of attendees from 186 different countries by the nation’s Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy.

With it, the opportunity for a global resolution to be forged, and the responsibility for each member nation to report back in three years on what they have done to address the problem.

“I think this is the most exciting and most powerful thing that we could have coming out,” Dr Remenyi says.

“Because that will put pressure back on the Australian Government on what it is they’ll be doing to address rheumatic heart disease in our own country.”

With the world’s eyes watching what moves Australia makes next, governments are under the spotlight to deliver some serious change — with or without the attention of millions of southern voters.