Sammy Butcher and Neil Murray reunite and remember Warumpi

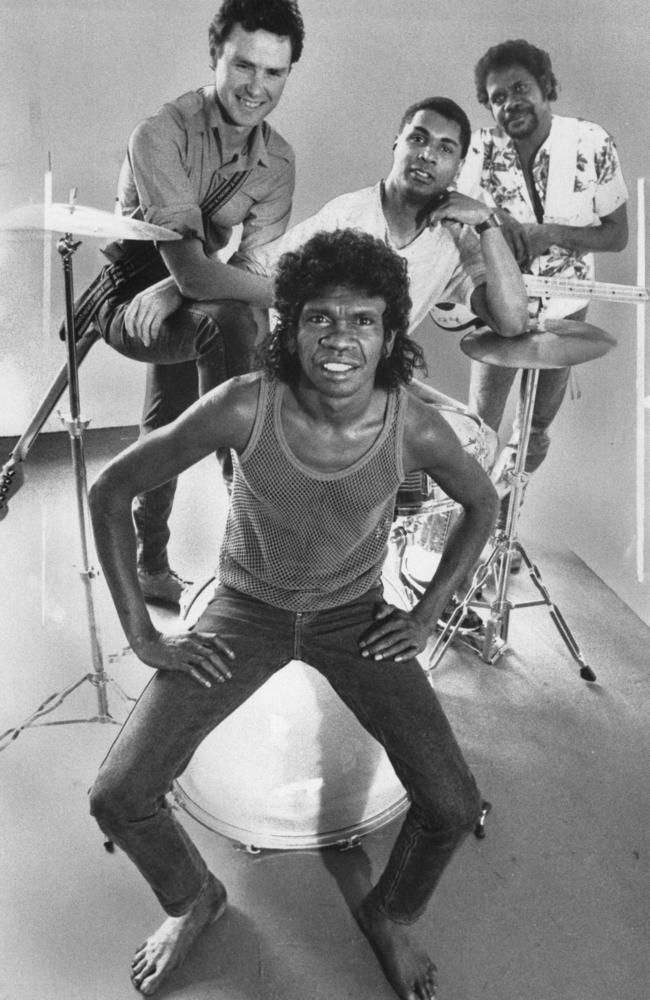

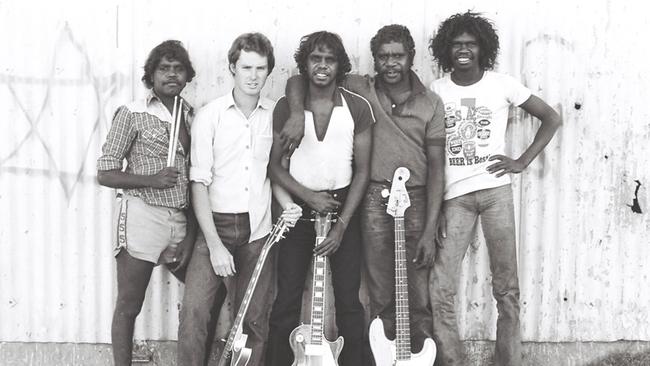

AUSTRALIAN rock and roll changed forever when three blackfellas and one whitefella joined forces in a remote Territory community.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

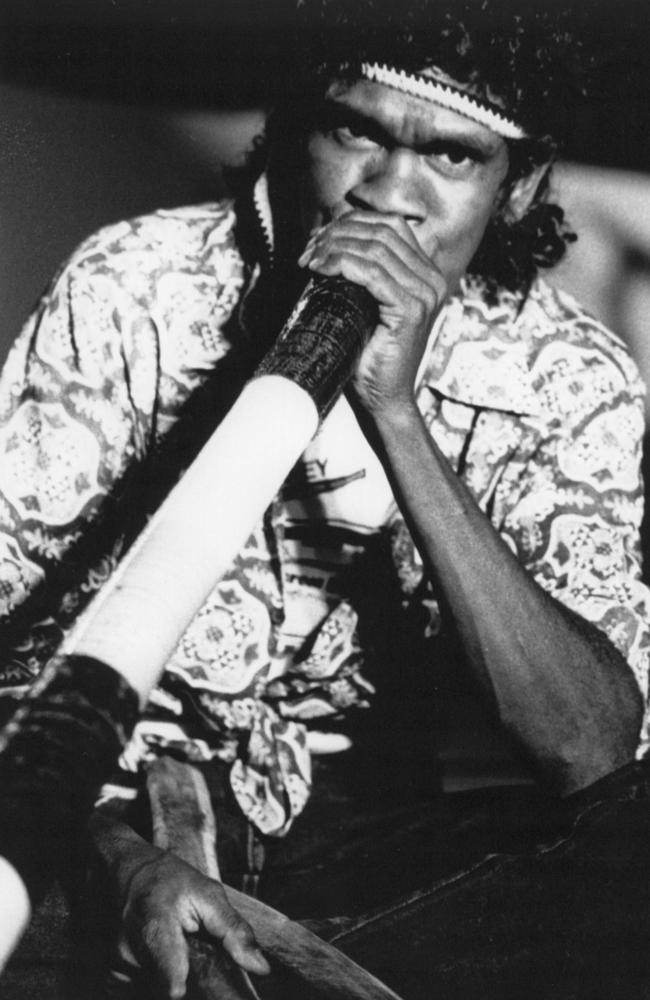

WHEN the former Warumpi Band singer lay dying, in the terminal stages of bone and lung cancers, he kept repeating, “I been a really bad person”.

The gangly saltwater man, Elcho Island-born George Rrurrambu - now George Burarrwanga for cultural reasons - passed away in 2007, aged 50.

It was the end of a monumental rollercoaster not just for George, but for the many who had surrounded him. Warumpi Band had been something of a wild beast – they appeared screaming from the obscure periphery of society, Papunya, a small community in Central Australia in the mid-80s, and launched into the nation’s rock and roll psyche.

They introduced something new to the world, and with it came teething problems.

Touring the country relentlessly as a four piece combo – three cultural men from remote Northern Territory, one whitefella Victorian – had its strains. Cracks appeared early. Gigs were missed. Punches thrown.

But the work they did was valid, pivotal, for the nation to learn something about itself.

Today, eight years down the dirt track from George’s death and 30 years since their debut album Big Name, No Blanket first appeared, founding Warumpi members

Sammy Butcher and Neil Murray continue to wield their instruments and carry on the footprints they forged into Australia’s cultural landscape.

Whatever George may have thought about himself, even up until the sorrowful end, he did good things – big things. And for Murray and Butcher, the work isn’t done yet, not by a long shot.

MARCH in the desert. The flies are doing their damndest to aggravate emotions of the 15 or so people in the room. Black hands flail around like windscreen wipers, swatting the insects to and fro.

Members of Papunya’s local authority have been summonsed for a meeting, to talk about issues of concern in their community.

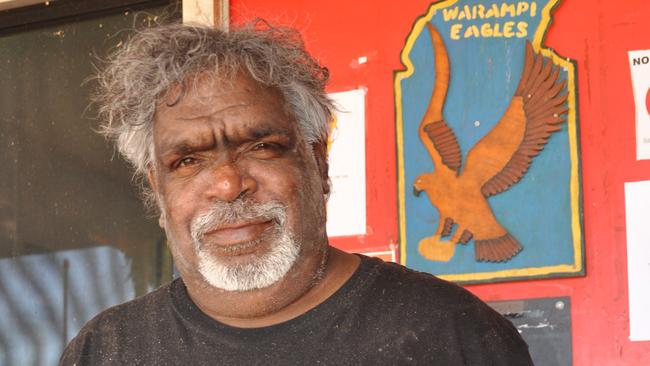

One of these is Butcher – who as well as being a giant of indigenous music, plays a leadership role for his region, holding high positions in the local authority and on the Central Land Council.

Here, his arms are folded, big brown eyes fixed on the speaker, brow creased in consternation.

The man talking is a frazzled Kiwi bloke, trying to push a message about the importance of keeping the Territory tidy.

Butcher is concerned. He is worried this man is going to try to disturb his hobby of fixing cars, by making him remove spare parts from his yard.

He makes sure the Kiwi is aware of his concerns, by consistently interrupting his spiel to voice them.

Growing increasingly agitated at the misunderstanding, “no, it doesn’t mean you have to stop fixing your cars, it’s just, ahhh…” the Kiwi blunders on.

Butcher keeps his eyes upon him, unblinking, not really getting it.

The meeting has the potential to drag on for hours.

ON the other side of the country, in a separate universe, songwriter Neil Murray is packing his bag to leave Lake Bolac, his home under the moody skies of western Victoria.

The plan is to drive to Melbourne and catch a plane for a solo gig on the Gold Coast.

He chuckles when asked about Butcher’s fascination with fixing cars.

“When I first saw the Bush Mechanics, I didn’t laugh,” says Murray.

“I thought it was a documentary.”

Murray spent formative years living in the desert – slogging it out undertaking laborious jobs on outstations, then turning his hand to teaching kids at remote schools in and around Papunya – an equally laborious slog.

He also, most notably, clapped eyes on a young Butcher, with whom he would discover a magical and lasting musical rapport.

“I was looking for work with Aboriginal people,” recalls Murray.

“And I particularly wanted to go to a community where the language was still strong.

“So I heard there was a job going on outstations, driving the store truck in Papunya,

and I ended up getting it.”

During his first weeks, before his own accommodation had been sorted, Murray bunkered in the spare room of a whitefella colleague.

One morning there was a knock at the door.

“There was this handsome chap, pretty cool lookin’ dude.”

The visitor was Butcher, asking if he could have a peek at Murray’s guitar.

“He’d heard I was in town and knew I had a guitar with me,” he continues.

“So I said ‘yeah sure’… I gave him my guitar, and I could tell he could play straight away. We were jamming by that afternoon.”

Once a denim-clad Yolngu man from the north came into the equation, George, with Sammy’s brother Gordon roped in to hit skins, history was forged. The Warumpi Band was formed.

What would ensue was one of the most energetic, unheard of explosions on to the Australian music scene – a crushing together of cultures, a proud embrace of aboriginality, the desert, sea and the crunch of guitars.

THESE days, due to the vast geographical expanse separating the homes of Butcher and Murray, performances as a pair are fairly rare.

Still, they have proved as one of the enduring relationships in Australian music.

Just last weekend, the duo appeared at the Barunga Festival, under the moniker of Tjungukutu, meaning ‘Coming Together’.

But it hasn’t always been smooth sailing.

Butcher’s connection to family and homeland often conflicted with Murray’s aspirations to be out on the road, or recording in big city studios, with Warumpi Band.

Both Butcher brothers were often reluctant to be coerced out of Papunya, and were infamous for pulling out of gigs at the eleventh hour, even after months of preparation behind the scenes.

Lisa Watts, producer of the 2013 film about the band, Big Name, No Blanket is married to Sammy’s younger brother Brian.

At the time, she reflected, the brothers were torn.

“They were torn because they had the responsibilities of their family, and to be present for their children.”

The Butchers’ reluctance cost the band one of their biggest chances to shine in spotlight – a tour with US megastars, Dire Straits. This squandered opportunity left Murray “devastated”.

“I think it’s affected him for the rest of his life,” Watts described.

“Some things … take a long, long time to get over.

“(There were) many opportunities they could have had, that they couldn’t accept because it was reliant upon Sammy and Gordon to accept those offers.”

After a sustained period of refusals to play further afield, Murray was forced to either rejig the line-up or face his hard work getting the band established disintegrating.

NEW Yorker and drummer Allen Murphy had not long been in Australia when he received a letter from Murray – an emergency request for a stand-in following last-minute word Gordon had failed to board a plane from Alice Springs to Sydney.

It was a prestigious gig - they couldn’t blow it off – a slot on the Ray Martin Show.

“That was the first Warumpi gig I ever did, playing Blackfella/Whitefella with the guys on the Ray Martin Show,” Murphy remembers.

“And I believe I met them that day – we didn’t really rehearse, we just kind of did it.

That was my first introduction to the guys.”

In lieu of Gordon, over the next years Murphy would be Warumpi’s drum thumping life raft, playing with the band on and off from the mid-80s into the early 90s.

“There have been certain jobs that have been game changers for me, and I guess Warumpi Band was definitely one of those,” says Murphy, who has now called home to Darwin for 20 years.

“There wasn’t a typical Warumpi Band gig. The thing that drew me to it the most was that Neil and George had great songs that were really about country.

“Which for me, I didn’t know anything about. That was my real introduction to indigenous issues and culture and Black Australia.”

Singing indigenous music, some in language and about desert country, had a resounding effect on the black population of the Red Centre.

Before Warumpi ever hit the myriad dirty bar stages peppered along the east coast, the band had built a solid majorly-indigenous fanbase in Alice Springs.

Centralian author Russel Guy, who helped tirelessly promote the band through his job at indigenous radio station CAAMA in the 80s, remembers a scene of tin shacks, sweat, grog and coppers.

“You’d have a capacity crowd, mostly black, a handful of whites who knew that it was a pretty cool place to be. And a couple of us in the middle of it trying to make it work,” says Guy.

“Sometimes the police would have to be called, or they would turn up. So having to manage that, in reference to the Town Council regulations, was like shadow boxing with Muhammad Ali.”

WITH their wildest days long since slipped away, Butcher has plenty of time to sit and take stock.

Out in Papunya, in the scarce midday shadow of the council building, he reflects on the last 30 years, and his gradual transformation from energetic young rocker to community elder and leader.

“I’ve seen a lot of change,” says Butcher.

“(I’m) a leader and a role model, anyway I can try and help others in need.”

He still chants the same mantra which kept him fastened to Papunya during Warumpi’s heyday – “you gotta be responsible”.

As he looks into the distance, there is a twinging element of regret for some of those missed opportunities.

“We would’ve been big. But because of family commitments, well, that’s life.

“You can only think back, when you get older, with grandchildren … but we did it. We made good music for everybody.”

From Lake Bolac, Murray also proudly reflects.

“There are a lot of fond memories. We had the best fun, and we delivered an important message to the country, to the mainstream.

“We were always received with such warmth … anywhere really, we always seemed to win over audiences.

“Just to see people come together at our shows – blackfellas and whitefellas, everyone there together. You felt there was something positive happening. There was a momentum - we were catching a wave that I hope is still there in Australian society.”

IN 2007, during the lead singer’s final days, Watts bravely helped him overcome his fears and prepare for whatever came next.

She sat by his bedside as palliative carer where she learned that George, too, had a few deep regrets.

“When you do palliative care you get to understand the person’s fears that perhaps were hidden before,” she said.

“I had a long, trusting relationship with George – he was my brother by relationship.

“I understood what motivated him – he was driven by this passion to be recognised as an indigenous knowledge holder, and he had incredible knowledge about his culture and traditions. And that’s all he wanted was to express that.

“But he also got caught up in a whole lot of things in his rock and roll career … and they’re the trappings.

“And he felt, in his last days, that he was a really bad person.”

George’s well-documented addictions to grog and ganja had a disastrous impact on the Warumpis – chaotic concerts, fights and the singer disappearing for days at a time.

According to Watts, in his last days of life, George managed to finally push through his feelings of self-loathing and “pass away accordingly”.

“He forged the indigenous music industry across Australia – he changed it from that country gospel into rock and roll and brought in a complete new wave – and kind of shocked the nation,” she said.

Murray stressed the point that during life George did manage to defeat his demons.

“In the end he did beat the grog and he got off it completely,” Murray said.

“Then I think ganja became a bit of a problem for him. That addictive personality, he was a rock and roller, so it kinda comes with the territory. Especially when you’re receiving all the adulation you get from the audience.

“But he did beat the grog and that was to his credit.”

IN a post-Warumpi landscape, contemporary indigenous music continues to thrive.

George’s fellow Elcho Island countryman Gurrumul is creating serious inroads into the international scene – he recently caused a sensation when he performed in the Big Apple, backed by Michael Jackson producer, Quincy Jones.

Desert rockers Tjintu Desert Band and East Arnhem Land’s East Journey are also carrying the torch of their predecessors, loyally touring and harnessing the same power of Aboriginal languages to get their messages across.

On the home front, members of the Butcher clan are thriving from the musical talent pulsing through their bloodstream.

Crystal Butcher, Sammy’s niece, a talented jazz vocalist, has been awarded entry to the New York School of Jazz, where she will depart NT for in September.

Papunya group the Tjupi Band are also spurring along. Touted as “the next generation of Warumpi Band”, the group has a firm focus on desert reggae as opposed to rock and roll.

“That’s what we do as a family,” says Watts.

“We focus on music and using that as a social tool to really bring the positive aspects into our lives.”

Arguably the country’s biggest broadcaster of modern Aboriginal music is CAAMA, which can be heard on the airwaves through networks across thousands of square kilometres in remote Australia.

General Manager of CAAMA Gerry ‘G-Man’ Lyons, who has been involved with the station in various guises for 18 years, says the impact of Warumpi remains profound.

“Warumpi Band, not just from a local sense, but a national and international sense – they made a major impact on indigenous music.

“They came in with powerful stories, dynamic sound, great composition, good songwriting. They influenced many of the genre back then as well.”

CAAMA’s studios in Alice Springs were where the band recorded much of their early material, “on the fly”.

Bands that come in to record in CAAMA these days realise they’re treading on some kind of sacred ground, says Lyons.

“Warumpi Band comes up many times in conversation (with modern musicians).

“They ask, ‘is this where Waumpi Band did their albums?’ … even though now they might be into hip-hop, they definitely know the artists.”

And Murray, the key keeper of the Warumpi flame, still marches the country’s long, lonesome highways to perform in rustic theatres on and off the beaten track.

The band’s chief songwriter delivers, like a prophet, the tunes of his life to eager audiences still awaiting the word - doing his bit to impart memories and wisdom from a special moment in Australia’s musical and social modern history.

“You can’t have your time again,” says Murray.

“You did what you could at the time. I’m one who looks forward, not back, and the things that I’m doing in my life now have been shaped by that experience. And they are different things, and in many ways I’m a different person.

“But it was all good – just to be able to play with George and Sammy and Gordon and all the others, to play again would be wonderful – do a victorious, triumphant lap around the country,” Murray laughs, a note of sad whimsy crackles in his voice.