Retired DEA agents speak about how they killed Pablo Escobar — the world’s biggest drug lord

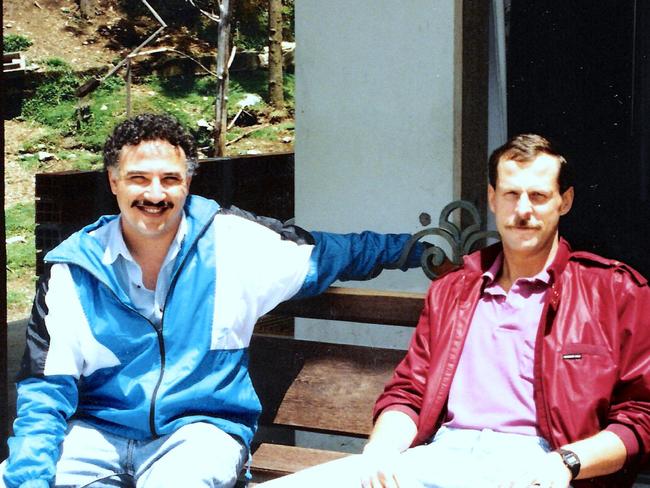

THEY were two smalltown cops tasked with capturing the most violent criminal in history — Pablo Escobar. Recently retired, they can now tell their story.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN Colombian drug lords put a $300,000 bounty on his head, Steve Murphy was worried.

“My wife threatened to cash it in on me a couple of times,” the recently retired American Drug Enforcement Agency officer recalled with a laugh.

Making light of the constant threat to his life was one way Murphy and his cop partner Javier Pena got through years of stress and mounting bounties as they looked to bring down the world’s most powerful drug cartel and its boss Pablo Escobar and end the global narcotics war.

It can’t be an overstatement to describe the period in the 1980s and early 1990s in Colombia as a conflict with an estimated 10,000 deaths, including 1000 police, 200 judges, hundreds of military and politicians and even a presidential candidate.

It was a time when car bombings trended, narco-terrorism as a term flourished and even an airline was brought down by an Escobar-backed bomb.

Three years ago Murphy and Pena retired from US law enforcement allowing them to speak openly and in detail of the US and Colombian plot to kill Escobar and end his Medellin Cartel’s multi-billion dollar trafficking of cocaine around the world including to the streets of Australia.

And speaking they are, with a series of police briefings, public speaking tours and on the hit television series streaming Netflix program Narcos, based on their extraordinary tale although spiced with more sex, girls and swaggering gun-toting good times than they remember.

But their revelations now of the Escobar era has appeal because it’s still happening today with different drugs, different countries but the same violence and drugs from places like Mexico and addiction epidemic not just in the US but Australia too.

News Corp Australia caught up with the men this month on the 23rd anniversary of Escobar’s death.

They are an affable pair, very much an odd couple akin to an old married couple who know what the other is going to say before they say it.

It’s actually hard to believe the pair, now aged 60, are the ones credited with having brought down the biggest cocaine cartel in the world, albeit with a small army of Colombian police and military behind them.

“It was a crazy time,” Pena said reflectively, of both their crime fight and seeing their story played out on Netflix.

“We lost friends, lot of our police friends killed, all the innocent people as well, the bombs but you know what we never suspected was it would be turned into a show or a story people would be interested in. It was a big case, a major case it began narco-terrorism but I never thought it would get this type of publicity.”

Pena was posted to Bogota in 1988 and Murphy three years later with the ultimate single brief to catch and or kill Pablo.

The men were not really sure what to make of the situation when they first arrived and anticipated a liaison role between US and Colombian authorities but within days it became clear the threat required frontline duties and they found themselves in helicopter gunships or armoured personnel carriers flying into action.

Indeed, Javier recalled the first day on the beat and his colleagues asked him where his gun was. He said it was in his holster on his hip and they told him to take it out.

It had to be permanently out when they were out, even driving to scenes his handgun had to be in his hand on his lap. It was the way things were.

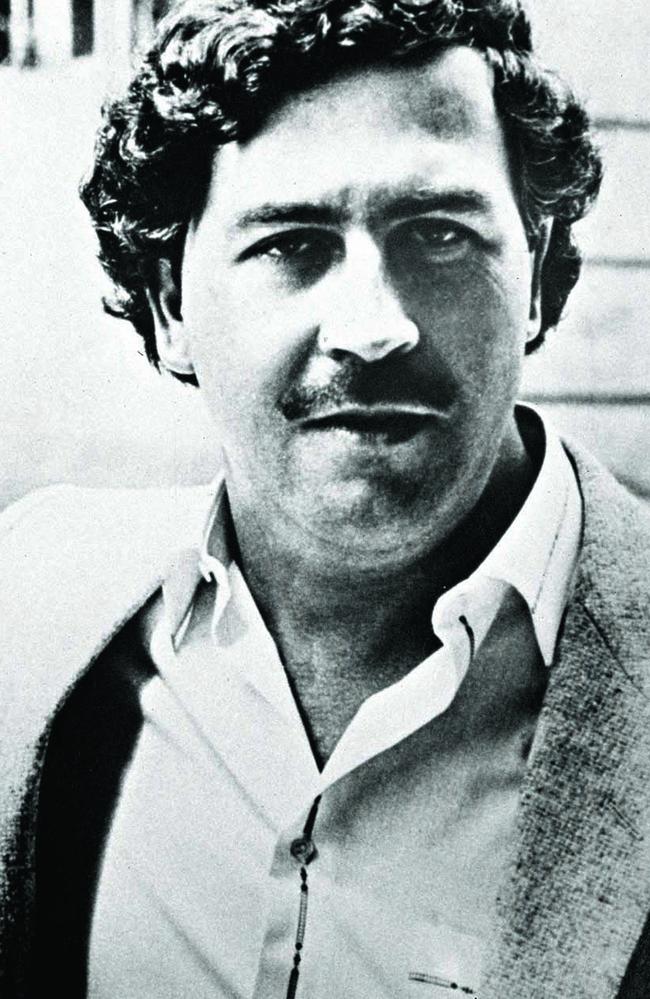

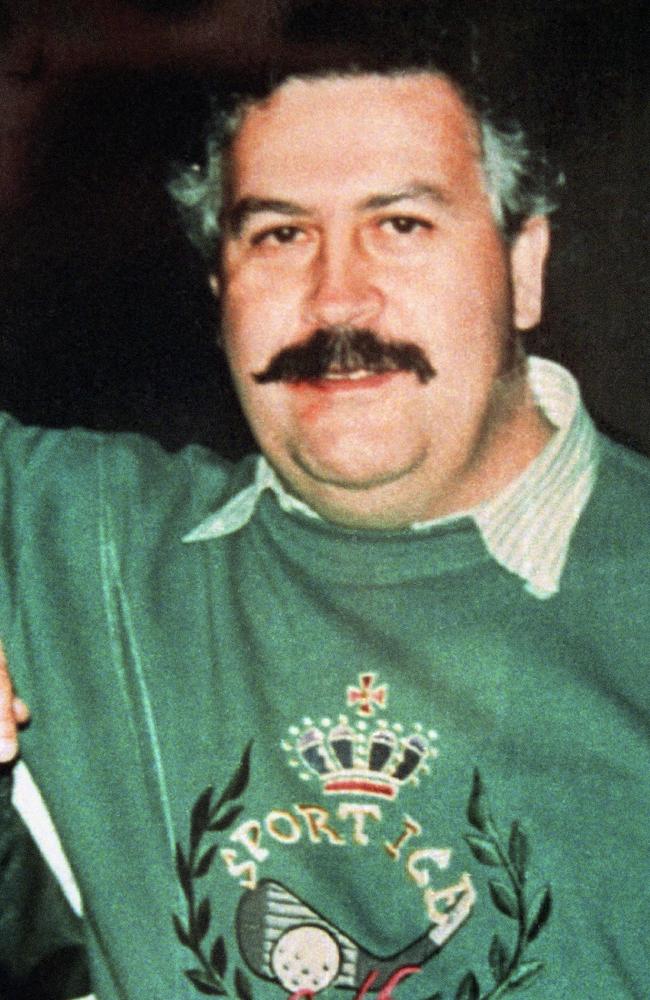

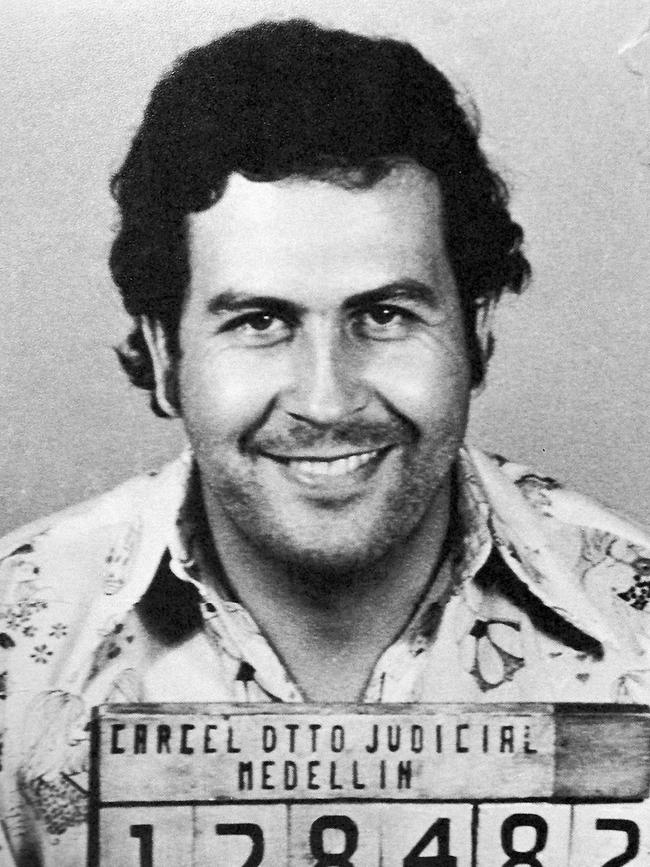

As a teenager, Escobar was a petty criminal on the streets of Medellin selling black market cigarettes on the street and stealing cars, but by 1976 the 26-year-old had a reputation as a ruthless thug.

In that year he was caught with a few kilos of cocaine, tried to bribe his way off the charges and when that didn’t work put out a contract on the judges and police involved in his case.

Charges were dropped, a scene that would be repeated many more times.

His elevation came from his buying an island airstrip in the Bahamas and a fleet of aircraft for which he would run drugs across the US and Europe.

At its height the Medellin Cartel controlled 80 per cent of the world’s cocaine market and was making $100 million a day.

Forbes magazine listed Escobar as one of the richest men in the world with an estimated private fortune of $30 billion.

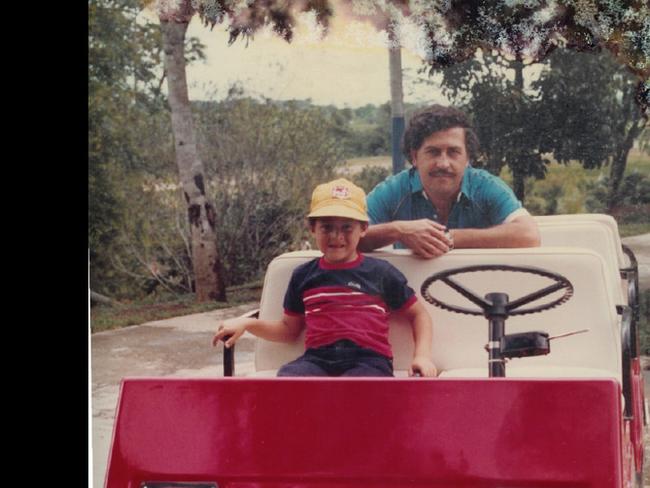

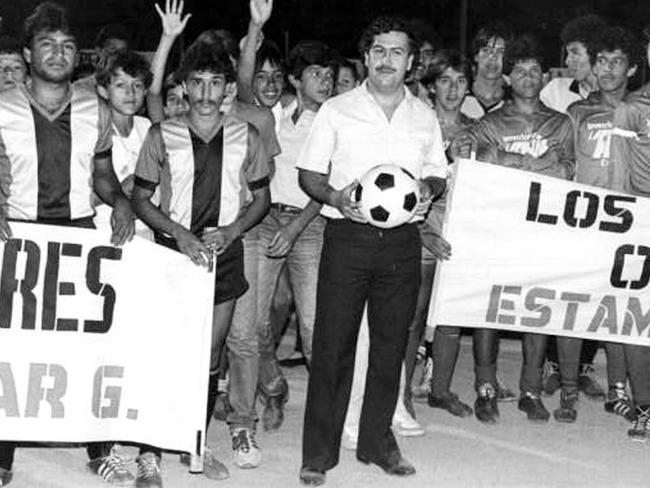

He spent some of his money building low-cost housing for the poor, football stadiums, schools, churches and hospitals as he cultivated mass support to the point he entered politics.

But his rise was fuelled by control and that meant a body count — police and politicians were often asked by his men “plata o plomo” (”silver or lead”) meaning accept a bribe or a bullet. Between 600 and 1000 police were killed, assassins paid as little as $100 for each cop kill. Escobar was believed to have been behind the 1989 assassination of Colombian presidential campaign Luis Carlos Galan and the bombing of Avianca Flight 203 where he hoped to kill another candidate Cesar Trujillo, killing instead all 107 people on board and three on the ground. Trujillo wasn’t on the flight and went on to become president.

The deaths of some Americans on-board spurred the US to take action both to dismantle his money empire through the FBI and Customs and with DEA men Pena and Murphy in the “Search Bloc”, the team formed in Colombia to stop the cartel.

“Our main strategy basically, and we had the best of best (Colombian) cops who were out there, was we concentrated efforts not on one person but the organisation,” Pena said.

“We couldn’t say there’s Escobar lets go after him, it doesn't work that way. You’ve got to start from the bottom, with the Sicarios, the assassins and the money launderers, the guys who have the aeroplanes, the guys bringing the money back, the guys in the United States who were cell heads in Miami, in New York. Go after anybody, everybody, and all these guys come out shooting, it was rare they give up, but concentrate on them, those running labs in Colombia, there was brutality to our efforts.”

Murphy said Escobar was brutal and no Robin Hood figure.

“He was a mass murderer, that was it,” he said.

“Yes he did some good things but he didn’t do anything for free, he expected things in return, he didn’t come out and say that and yes he went out and built all that nice low-cost housing for all those living in the dump and that is a good deed and he did health clinics and soccer fields and literally did give out cash but what he wanted in return and what he got in return was whenever he needed new assassins, Sicarios, he would go to that barrio (district) and he would recruit some bodies.

“These are people who didn’t have anything and suddenly they have a roof over their heads, running water and electricity and someone comes around occasionally then of course they are going to look at him like Robin Hood. But there was a payback … It was unbelievable how many stepped up to fight for him.”

With a known bounty of their heads and the endless bombings and death, the men considered giving up but knew they owed it to their comrades to continue in their pursuit.

When Escobar unexpectedly surrendered in 1991, on an amnesty agreement he could have a reduced sentence and live in a jail he had built which resembled a resort complete with a bar and jacuzzis and under laws he financially supported to never extradite a Colombian to the US, the Search Bloc was disbanded.

As reports of his luxury deal surfaced and under international pressure, authorities looked to move him to a conventional jail, tipped him off as such prompting his “escape” and the killings resumed.

He would elude authorities for another year before a rooftop shootout saw his death on his 44th birthday in December 2, 1993.

“After his escape we just wished he would turn himself in, ‘let’s all just go home, stop the killings, the bombings, the assassinations, let’s just pack our bags let him surrender and get out of here,” Pena recalled.

“But you know what you’d get that vibe, that adrenaline when you would see some atrocities, the bombings, the killings, the bounties on police kidnappings that would say ‘man this cannot be happening, this guy needs to be taken down’.

“So it was that type of feeling that kept you going but believe me there was plenty of times we were just ‘let’s call this quits, he won, we lost let’s get out of here’.

“I had to move house a couple of times. But it kept you going because the police you worked with day in day out. I get criticised for this but you know it’s not about seizing money, seizing dope, it’s about killing Pablo Escobar because a lot of innocent people, police officers, politicians, presidential candidates — I mean who kills a presidential candidate? — an attorney general, scores of hundreds and thousands of innocent people he killed.”

The bounty on the men’s heads went up after they were forced to remove Escobar’s children from an airplane because they inadvertently got visas to the US.

“He knew who we were, only two DEA agents assigned to the case among the local police officers so yeah he knew,” Pena said.

On the Netflix show Narcos, the men said it was funny to see how they are portrayed and there were artistic licences; Pena said he was single but didn’t have half the women of his handsome on-screen character, played by Pedro Pascal from Games of Thrones fame.

But the highlight of the men’s career, they say, will be to take to the stage at the Sydney Opera House and tell their story to rows of police, crims and Narcos fans.

“We never imagined we would be asked to do this, holy cow the Sydney Opera House,” Murphy said of his shows coming up in Sydney and Melbourne next July.

“We’re just a couple of small town cops … who worked a case.”

Originally published as Retired DEA agents speak about how they killed Pablo Escobar — the world’s biggest drug lord