Finally, compensation for a stolen life

SOME of the children who lived in the old Retta Dixon home were stolen from their people, some were surrendered, writes ELLIE TURNER

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SOME of the children who lived in the old Retta Dixon home were stolen from their people, some were surrendered.

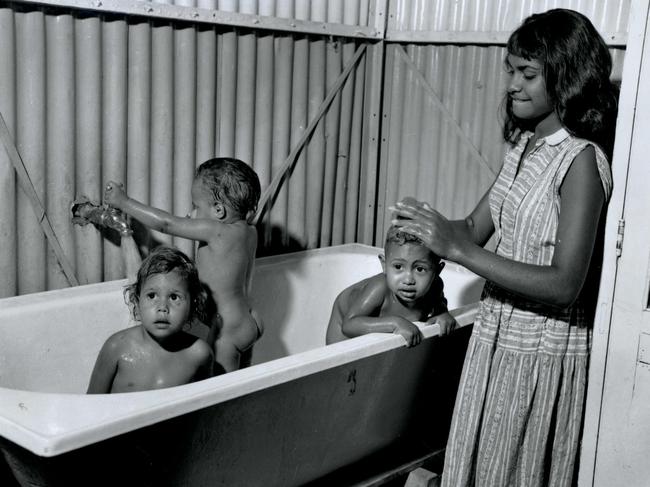

But once they were in care under the Commonwealth’s assimilation policy, the non-denominational religious organisation that ran the “half caste” home failed to ensure they were protected. Instead, many vulnerable children were indoctrinated, humiliated and exploited.

Some of the survivors of physical and sexual abuse at Retta Dixon made history with a class-action lawsuit against the Commonwealth, Australian Indigenous Ministries and convicted paedophile Donald Henderson.

And a settlement has been reached.

The 71 former child residents of Retta Dixon involved in the civil case will be compensated for the wrongs perpetrated against them by people they should have been able to trust.

Irene Yanner, 65, sits in her leafy garden in northern Darwin, her dog Jackson sitting at the gate and chickens pecking at the grass.

She has eight children and one adopted son, 38 grandchildren and eight great grandchildren. Ms Yanner is proud of her family.

But she said being raised without parental affection in Retta Dixon — where she was sexually, physically and emotionally abused — contributed to her difficulty showing her children love as they grew up and her discomfort at being touched.

Ms Yanner said she didn’t see the compensation as closure.

“I would have liked to see all the people who hurt us prosecuted — not just the paedophiles, there were some sadistic missionary women as well,” she said.

“It would have helped knowing they were punished.”

On the other hand. she said she was glad the settlement recognised the wrongs perpetrated against children at Retta Dixon, even if it didn’t undo them.

Ms Yanner said one house parent forced her to kneel on bird seed in a corner from lunch to dinner time one day because she refused to pray.

“The seeds were embedded in my knees,” she said.

She was also flogged incessantly, once to the point where her injuries were so bad she ran away from Retta Dixon and hid at her mum’s house in Nightcliff, where she lived with a Hungarian man who threatened to report the missionaries to police for the brutal beating when they came looking for her. Ms Yanner had two babies by the time she was 16 — “a man tells you he loves you, and all you want is to be loved,” she said — and met her partner Phillip Yanner in 1969.

They moved to Burketown, where he was an indigenous community leader, and he taught her about family.

“He kept me grounded,” she said.

Phillip died in 1999 and Ms Yanner moved back to Darwin, where she was born, about 16 years ago.

The civil lawsuit began after the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse heard evidence alleging rape, sexual touching and horrific assaults from former child residents of Retta Dixon in September, 2014.

The main alleged perpetrators were former house parents Desmond Walter, George Pounder, Judy Fergusson and Donald Henderson.

There was also evidence some children were abused by other children.

Retta Dixon became a focus for the Royal Commission after two former residents, Barbara Cummings and Sue Roman, rounded up others to tell their stories in private sessions.

Without their tenacity, the horrors that happened may never have been aired.

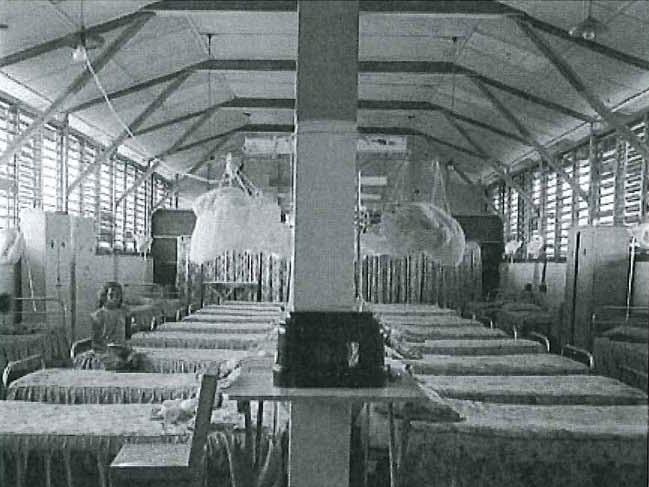

Retta Dixon opened as a dormitory-style home at Bagot Reserve in 1946.

The home moved to Karu Park, on the corner of Bagot and Totem roads, where cottages were built in the early 1960s.

It closed its doors in mid-1980.

Aborigines Inland Missions, as AIM was then known, employed “house parents” and a superintendent to run the home, where children were humiliated for displaying signs of trauma and distress, including wetting the bed.

One house parent stabbed a child in the hand with a can opener, and girls were groped, perved on in the shower and chained to their beds.

When children were brave enough to report sexual abuse to superintendent Mervyn Pattemore, he ignored them or caned them for “lying” rather than reporting paedophiles to police.

The commission found AIM failed in its duty of care.

But the results were inconclusive when it came to the Commonwealth’s culpability, which the commission found couldn’t be determined due to a lack of evidence, with many records lost or destroyed.

“A question remains as to whether it should have taken action to protect the residents of the home from sexual abuse,” it stated.

Federal welfare officers were aware children in Retta Dixon were sexualised from the early 1960s, when a government worker reported a 13-year-old girl got “12 strokes of the cane for sex play with a little boy”.

Former residents identified alleged rapist and convicted paedophile Donald Henderson, who now lives in Queensland, as the major sexual offender.

One man gave evidence at the Royal Commission that Henderson raped him in the chook pen at Retta Dixon.

In 1975, Henderson was charged with seven offences against five Retta Dixon home children but the cases collapsed.

In 1984, Henderson was convicted without penalty when he admitted he indecently assaulted two young white brothers at Casuarina Pool.

Eight years later he was declared a “person of interest” after police received a report that he was lurking near boys at the Anula shops in northern Darwin.

In 1998, four people came forward and alleged historic sex offences against Henderson.

The commission found the four-year police investigation lacked strength and resources, and the Director of Public Prosecutions failed to follow procedure when withdrawing charges on the ground conviction was unlikely.

One man, who asked to remain anonymous, was molested by a female house parent after his non-indigenous father surrendered him to authorities when he was about five-years-old.

He said he escaped the worst of Henderson.

“He was a charismatic man and a ruthless predator,” he said.

The boys nicknamed Henderson “ticklefoot”, due to his penchant for sitting young children on his lap and tickling their feet with a feather duster.

About a quarter of the people involved in the class action were victims of Henderson.

The man reiterated the overarching feeling among his fellow survivors — that the settlement was more about AIM, the Commonwealth and Henderson recognising wrongdoing and suffering than the money.

Darwin lawyer Bill Piper, who ran the class action, said the final deeds had been prepared and signed.

He said the settlement avoided the costs and stresses involved in drawn-out civil litigation.

“This settlement happened in a ‘flash’, in legal timescales,” Mr Piper said.

He said he was uncertain if the case would open the door for other lawsuits.

“It leaves open the question — can institutionalised kids from the stolen generation claim for failures of authorities to care for them once they were placed in care?” he said.

“There was a huge raft of evidence available from the Royal Commission that might not be present in other cases.”

Mr Piper said the Royal Commission was a “third crack” for many people who identified as “stolen generation”.

The High Court decision of Kruger vs. the Commonwealth in 1997 found the old Commonwealth assimilation policy was constitutional;

The Federal Court decision of Cubillo and Gunner vs. the Commonwealth found the way authorities implemented the assimilation policy was not actionable;

But the findings of the Royal Commission made it clear that those who suffered injury, loss or trauma would have reasonable prospects in pursuing civil action.

The Federal Government has announced a sexual abuse victim redress scheme. Mr Piper said the scheme could represent an alternative to litigation for those with a Commonwealth connection.

He said Territorians who missed out on the class action may be able to claim damages under the scheme.

Mr Piper said about 90 per cent of people involved in the class action were in favour of a memorial to institutionalised children across the NT at Karu Park.