All the holes in the Keli Lane trial: the missing witness, the bizarre theory, the silent defence

A DETECTIVE who helped put child killer Keli Lane behind bars now thinks she shouldn’t be there due to serious flaws in her murder trial.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AN EXTENSIVE reconstruction of the murder trial of Keli Lane, jailed for 18 years for killing her baby, has uncovered serious flaws and concerning new questions.

ABC journalists Caro Meldrum-Hanna and Elise Worthington have delved into the story, which captivated Australia for more than a decade, for Exposed: The Case Of Keli Lane.

In Tuesday night’s third and final instalment, a forensic psychologist examined Lane for the first time and concluded it was unlikely she killed two-day-old Tegan in 1996.

It also revealed the deal done to prevent a crucial witness from testifying, the judge’s hints to the defence that were ignored, and the origin of a baseless theory briefly presented as fact.

A decade after baby Tegan was last seen alive, the matter was referred to the New South Wales Homicide Squad in 2006 and Detective Sharon Rhodes began investigating.

She was tracked down by the ABC and spoke for the first time about her involvement in bringing the case to trial.

Despite hundreds of hours of police work, Ms Rhodes recalled police had “absolutely nothing” to pin to Lane by the end of 2008.

“I used every trick in the book. An undercover strategy, covert DNA samples, every resource that was available. There was nothing. Absolutely nothing. We didn’t have anything,” she said.

NOT REMOTELY READY

The police investigation had turned up only circumstantial evidence and detectives doubted they had done enough to establish a motive beyond reasonable doubt.

The case would be especially difficult to prove without a body. There had been a number of careful searches without any result.

Ms Rhodes said police sent a brief of evidence to the Department of Public Prosecutions in order to receive legal advice.

“We weren’t in a position to charge Keli Lane at that point, so we sought advice,” she said.

But Nicholas Cowdery QC, the former NSW Director of Public Prosecutions, felt there was enough material to obtain a conviction.

“My own view was there was a case of murder to be prosecuted … it got priority over other cases,” Mr Cowdery told the program.

In November 2009, Lane was charged and Crown Prosecutor Mark Tedeschi was called up.

“It was entirely a circumstantial case,” Mr Tedeschi said.

“We had to prove death without a body. We had to prove that whatever happened to baby Tegan, that she was deliberately murdered by Keli Lane.”

However, he told the ABC that at the time he felt the matter was “99.9 per cent ready” to go to trial.

It’s a claim that Ms Rhodes strongly refutes, saying: “We were not ready. Did he say that? You’ll have to pick me up off the floor. No. No. We weren’t ready.”

Justice Anthony Whealy QC, the judge who oversaw the Supreme Court trial, would later chastise the prosecution for not being prepared.

Lane’s legal team was being hit with documents and discoveries throughout the trial, which swamped them.

“It should’ve been completed before the trial. This was a case that we being prepared on the run, there’s no doubt about it,” Justice Whealy said.

DEFENCE IGNORED HINTS

The final episode of Exposed also raised questions about the robustness of Lane’s defence in court.

The prosecution orchestrated a clever tactic to allow elements of Lane’s personal live — her sexual partners and previous unwanted pregnancies — to be heard alongside the murder charge.

It was done by attaching perjury charges to the murder charge, relating to testimony that Lane had given at a coronial inquest.

Justice Whealy told ABC he asked the defence if they wanted to make a motion to strike the charges, but Lane’s legal team declined.

“You could say I dropped the hint,” Justice Whealy said.

“She was now exposed to a serious attack on her credibility that wouldn’t otherwise have been available.”

When Mr Tedeschi gave his opening remarks to the jury, they included a shocking theory about what Lane did with Tegan’s body.

After killing the baby, Lane had buried her remains in the ground beneath the spot of a Sydney Olympics stadium in Homebush.

“It was ruled by the judge to be not appropriate and it was withdrawn by the Crown (the next morning),” Mr Tedeschi said when asked about the theory.

By then, the damage was done and Justice Whealy asked the defence if they wanted to request a mistrial.

In his view, the trial could have been aborted. But the defence declined.

SOURCE OF THE THEORY

When pushed by the ABC, Mr Tedeschi refused to discuss the Olympic Park burial theory that had been presented and withdrawn.

It was his argument that given it wasn’t technically on the record after being withdrawn, he could not speak to it — including where the theory originated.

But the ABC heard from former child safety officer John Borovnik, who originally tipped the police off that something was not right.

Mr Borovnik had followed the case and become emotionally invested in it — he has Tegan’s name tattooed on him — and revealed the Olympic Park idea had been his.

“He used my theory that I sent to him weeks (before),” Mr Borovnik said. “It was a theory.”

NOT ‘THE REAL KELI’

The way Lane was painted in court was as a ruthless and ambitious water polo player who was desperate to compete at the Olympics in Sydney at any cost.

Water polo was to be an officially recognised sport at the Games and Mr Tedeschi told the court that Lane wanted to be there representing Australia.

It was why she had given away two babies, had two abortions and apparently killed Tegan, he convinced the court.

“She was incredibly ambitious. It meant a tremendous amount to her,” Mr Tedeschi told the ABC.

But Les Kay, her former water polo coach, said Lane had never expressed a desire to be an Olympian. Her friends and former teammates agreed.

More than that, but the coach of Australia’s Olympic team at the time said Lane would never have been in contention.

NURSES’S MEMORY RETURNS

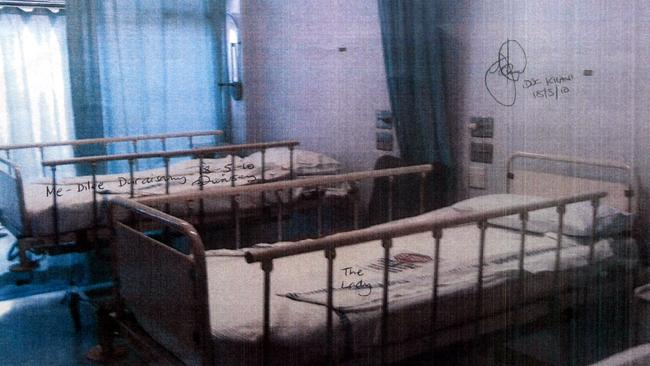

During the original investigation, the midwife who discharged Lane and baby Tegan two days after the birth said she had no specific recollection of the mother and child.

Official nurse’s notes from the hospital had the time of discharge listed as 2pm.

But during the trial, midwife Ann Hanlon came forward to say she then remembered Lane and that she left the hospital much earlier, around 11am.

“It was a remarkable memory return,” Ms Rhodes said of the U-turn.

The recollection gave prosecutor’s a new timeline, as the paperwork had previously shown Lane leaving the hospital at 2pm and being at her parent’s house on Sydney’s North Shore an hour later.

Lane attended a friend’s wedding that afternoon, where she was photographed in attendance.

Her arrival at her parent’s house and presence at the ceremony were not disputed, so with the original timeline there would have been only a matter of minutes to kill Tegan and dispose of the body.

But testimony of her earlier departure from the hospital removed that question mark.

Lane maintains that she handed over the infant to her biological father, a man she’d had a brief affair with named Andrew Norris or Morris.

“Andrew was there … there was a lift at the end of the corridor. I did have a moment of … maybe I could just take her. It’s so painful,” she told the ABC.

ANDREW COMES FORWARD

The jury was meant to hear testimony from a man named Andrew Morris who claimed he had a one-off sexual encounter with Lane.

They were told in Mr Tedeschi’s opening statement that they would hear from him and that they never had a baby, but he never appeared.

The ABC obtained a video interview with him, conducted by police, in which he recalled having sex with Lane at North Narrabeen Surf Club.

At the eleventh hour, he was scratched as a witness.

“We had him ready to go, sitting there in that witness room, and then for reasons I don’t understand we sent him home,” Ms Rhodes said.

It was the result of a deal between the prosecution and defence, which Mr Tedeschi would not discuss. But the ABC discovered that it was a swap — the Andrew Morris testimony would not be heard in court if Lane’s lawyers agreed not to call one of their witnesses.

Mr Morris was also tracked down and now doubts whether he ever met Lane.

“I was led to believe that’s who I slept with. It snowballed and just got bigger and bigger. I didn’t feel … I couldn’t turn back,” he said.

He said he couldn’t say with confidence if it was Lane he met on the beach that night.

Ms Rhodes said the man’s admission was troubling, and agreed that it appeared he could have been led on or coached by police.

“Yes, I can see that in hindsight, yes I can. I don’t like admitting that but yeah, I can see that,” she said.

THE MISSING WITNESS

The defence witness the jury was supposed to hear from was Natalie McCauley, one of Lane’s friends.

Ms McCauley was to tell them about a night in the summer of 1995 when Lane told her about a relationship she was having with a man named Andrew.

“She talked about this guy she was having an affair with, Andrew. That’s clear because it’s my brother’s name. She told me about Andrew at the right time period we’re talking about,” she said.

It was significant because no one else could corroborate the mystery man’s existence and there was no record of him.

Ms McCauley, who works in child protection for the United Nations, told the ABC she was telling the truth about the conversation.

“I am passionate about children’s rights. I love children. Every day, my every waking hour, is about protecting kids. I’m not about to let my friend get off easy if she’s hurt a child.”

Ms McCauley was shocked to discover her testimony was scrapped because of a deal. And she was certain of the impact it could’ve had on the trial.

“I’ve got two words for you — reasonable doubt,” she told the ABC.

Ms Rhodes agreed that she would have done “damage” to the prosecution’s case.

DEFENCE TEAM GOES COLD

When contacted by the ABC, Lane’s lawyers at the trial declined to speak and share their insights for the documentary series.

Ben Archibald, a former Victorian Police officer turned lawyer, who was also a contestant on the reality TV series Big Brother, hung up when the journalists called him.

He had called zero witnesses during the trial and had brought on a barrister just three weeks before the trial.

That barrister, Keith Chapple, and another lawyer assisting Mr Archibald, also declined to speak.

“I wish I told my side of the story,” Lane said. “There’s a lot more to me that the jury needed to know that the defence didn’t give them.”

NO ASSESSMENT DONE

Another step Lane’s lawyers did not take was to have her assessed by a psychiatrist before the trial. It was something the ABC arranged.

Dr Ann Buist, a professor of psychology and specialist in mothers who are violent towards children, has assessed hundreds of cases of abuse and more than a dozen cases of murder.

Dr Buist met Lane in prison and conducted an assessment.

“There’s a great deal of murkiness here. She’s the hardest, most difficult case. She differs very much to the other cases I have seen,” she said.

However, it was her view that Lane could not be diagnosed as delusional, evil, a pathological liar or a narcissist.

“Certainly not in a diagnostic sense, absolutely certain of that.” she said.

“From a very early age she got the message that her family didn’t like dealing with negative emotions.”

Lane was also the victim of a date rate assault when she was 15, which was her first sexual experience and for which she still blamed herself, Dr Buist said.

It was not her assessment that Lane had killed Tegan, saying: “I can’t find a coherent narrative (for murder) from a psychological sense.”

She also believed that Tegan may still be alive.

WHO WAS TEGAN’S FATHER?

Lane has long maintained that Tegan was fathered by a man named Andrew Morris or Norris — she was eventually certain it was Norris.

At the end of the episode, after pulling apart the police investigation and the trial, could not escape one final piece of the puzzle.

Dr Buist told them that “there’s something off, something not quite right” about Lane’s story regarding Andrew.

“Her manner … was too superficial, her body language changed, there was something there that didn’t ring true and I can’t say what,” she told them.

‘Australia do you recognise this face?’ This is the man Keli Lane claims she gave baby Tegan to in 1996. Send your tips to exposed@abc.net.au does he exist? #EXPOSEDabc #KeliLane pic.twitter.com/qERCUu9cXU

— Caro Meldrum-Hanna (@caromeldrum) October 2, 2018

It’s from this point that the series ends with a bombshell, when Lane is confronted and asked point blank if she is sure about the man’s name.

She concedes that she can’t be certain.

“I don’t know if what he told me was the truth. Maybe I’ve made a mistake.”

It was the first time Lane admitted that Tegan’s father might not be a man known as Andrew Norris or Morris.

A LASTING IMPACT

When the jury retired to deliberate, Justice Whealy felt that the prosecution had not established the case beyond a reasonable doubt.

“I thought the jury might take a similar view,” he recalled.

In the end, 11 jurors felt Lane had killed her daughter while one did not, which resulted in a majority verdict and a conviction. Lane was sentenced to 18 years in jail.

“In my mind, I’ve never been certain. And now, years later, I haven’t changed my attitude,” Justice Whealy said.

“By the end of the trial, it had been such a harrowing experience for me that I no longer wished to preside over any criminal trial as a judge. I didn’t do any more criminal trials.”

Ms Rhodes believed that Lane killed her child, and she still does, but the former detective does not accept fair justice was served.

In her view, Lane should not have been convicted.

“Yes, my team got a guilty verdict, but I would happily give all that back to have not almost lost my mind,” she said.

“I was medically discharged with PTSD from the police. This case broke me.”

You can catch up with every episode of Exposed: The Case Of Keli Lane on ABC iView.

Originally published as All the holes in the Keli Lane trial: the missing witness, the bizarre theory, the silent defence