King, koalas, conservation: The extraordinary story of John and Elizabeth Gould

With London’s scandal-prone society obsessed by the king’s newest pet project, it fell to a man famed for his work with Australian wildlife when tragedy struck.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was the savage summer of 1839 and in the thick undergrowth of the Upper Hunter Valley of New South Wales, John Gould donned his battered bush hat with bird feathers stuck in the rim like a crown.

For hours every day as drought ravaged the brown land all around the Liverpool Range, the world’s foremost expert on birds made a series of clucking noises as he danced about in the bushes, waggling his feathered head in the hope of finding the objects of his desire.

The two Indigenous guides who had led Gould to this place and convinced him to wear a crown of feathers must have fought hard to suppress their laughter at the antics of this eccentric and obsessed Englishman.

Gould was looking for lyrebirds to illustrate and document for the landmark seven-volume masterpiece Birds of Australia that he and his artist wife Elizabeth would showcase to the world.

‘SHY AND DIFFICULT’

The Goulds had arrived in Hobart six months earlier, in September 1838, with a plan to document and illustrate every species of Australian bird.

Elizabeth stayed in Hobart to give birth to their seventh child as Gould journeyed on to Yarrundi Station, run by his brother-in-law Stephen Coxen near Scone, 250 kilometres north of Sydney.

Gould made his way to the upper reaches of the Liverpool Range, assisted by two young men of the Geawegal people known to the Europeans by their nicknames Natty and Jemmy.

Gould described them as “two intelligent and faithful natives of the Yarrundi tribe”.

He often remarked on the reverence Indigenous Australians had for nature and, in contrast to many of the colonists, wrote about them with affection and sympathy for their struggles against invincible forces taking their land and food sources. When compiling Birds of Australia, when possible, Gould noted all the Aboriginal names for the birds he collected alongside their English and Latin counterparts.

Jemmy and Natty knew just where to find lyrebirds in the Liverpool Range, though they were particularly elusive birds, Gould calling them the “most shy and difficult” that he had ever encountered.

Lyrebirds are ground dwellers noted for the male bird’s huge tailfeathers, which, in courtship displays, are fanned out in the shape of a lyre.

Gould was astounded by the way the birds could mimic all manner of sounds. He thought it such a remarkable creature that he advocated Australia adopt it as a symbol for the colonies and later used an illustration of it in all its fanned-out glory for the covers of his Birds of Australia series.

His burning desire to possess some for study saw him climbing and clambering over difficult terrain, risking his neck over steep ravines and deep gullies, suffering cuts and grazes as he and his guides barged through “rugged, hot and suffocating brushes” and thick, twisted undergrowth.

At the suggestion of Jemmy and Natty, Gould took to wearing the tail feathers of the male lyrebird, fully fanned out, in his hat, bouncing about in the undergrowth to mimic the bird’s constant dancing. The move eventually proved successful though Gould must have suspected after a while that his guides were having a laugh.

FOUL-MOUTHED MISTRESS AND A GIRAFFE

Gould and Elizabeth had become the most important publishers of wildlife books in Britain while still in their early 30s, Gould’s reputation initially boosted by his reputation as a young taxidermist, the royal “animal stuffer” for the infirm King George IV.

The King had become a royal recluse, spending most of his time at the Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park. George IV lived there with his married and foul-mouthed mistress, Lady Elizabeth Conyngham but in 1827 he had found a new love, newly arrived from Africa.

Towering over him by almost a metre and a half, she was the most exotic creature His Highness had ever seen, and he was besotted.

When he could be raised from his sick bed, the king would sometimes drive his pony chaise, surrounded by guards and courtiers, to his menagerie of what he called his “gentle animals” at Sandpit Gate inside Windsor Great Park. Sometimes he took the young Princess Victoria with him.

The King’s menagerie contained gifts from sultans and kings, including exotic animals such as elks, chamois, gazelles, gnus, monkeys, roebucks, musk deer, mandarin horses, Brahmin bulls, a zebra, a leopard, a llama, tortoise and kangaroos.

His prized pet was the most divine creature he had ever seen, a creature so strange that many observers thought it was not of this world. It was a Nubian giraffe, a diplomatic gift from the Egyptian pasha Muhammad Ali.

The first giraffe to arrive in London had died in 1805 just three weeks after landing so the arrival of George IV’s exotic gift had Britain transfixed.

Gould and Elizabeth were quick to join the crowds visiting the royal menagerie to see the first living specimen of a giraffe in the flesh, and artists hurried to capture her likeness.

One observer reported that the king’s giraffe was an “extremely gentle and good natured” animal and that “Nothing could give an idea of the beauty in her eyes – Imagine something midway between the eye of the finest Arab horse and the loveliest southern girl, with long and coal-black lashes, and the most exquisite beaming expression of tenderness and softness, united to volcanic fire.”

The giraffe craze took hold in England.

Candlesticks, printed fabrics and ceramics were all inspired by the giraffe’s appearance and fashionable magazines promoted interior designs using giraffe-based colours and patterns. English women had never worn their hair so high.

King George doted on the animal, visiting her constantly in the special building erected for her at Windsor Castle. But the giraffe’s knees never recovered from her long journey from Africa, when transported on the back of a camel through the Sahara to the docks in Egypt, and they were constantly bandaged. The king felt her pain. At 64, his gout and obesity had caused weakness in his own knees too.

The Goulds and many others observing the giraffe feared that, despite assurances from the animal’s keepers, she was ailing.

George IV took great pains to show off his prize at every opportunity.

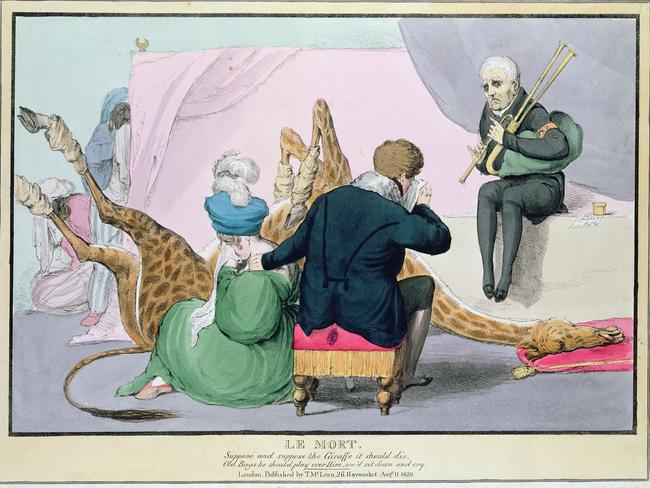

For critics of the king, and there were many, his obsession with the young giraffe was more evidence of his self-indulgence and of his desire to put entertainment and ego above the needs of his subjects. Caricatures lampooned his fixation on his latest toy.

But the giraffe’s health was no laughing matter. The year 1828 had been an unusually wet one in England and the winter months going into 1829 were extremely cold. The bitter contrast to the dry heat of North Africa played havoc with the giraffe’s constitution, and her declining health mirrored the ageing king’s own woes.

One observer noted that by 1829 the giraffe appeared “very weak and crippled … She is occasionally led for exercise round her paddock, but she is seldom on her legs. When she first arrived, she was exceedingly playful, and perfectly harmless but she is now much less active, although as gentle as before.”

The king’s giraffe finally succumbed on 11 October 1829 and His Highness immediately summoned his renowned animal stuffer.

Gould knew that being tasked with preserving the carcass of the giraffe was an unusual honour that was unlikely to come his way again. The animal was something of a national treasure and the pride and joy of Europe’s most powerful monarch.

Gould took great care to ensure that the king’s giraffe lived on at least as a lifelike curiosity for museum patrons.

Thanks to Gould the giraffe would have a much greater audience dead than alive.

TAKING AUSTRALIA TO THE WORLD

The Goulds soon turned their attention to Australia with a dream to document all the fascinating, stunning and unique wildlife in that vast continent.

They wanted to take the stories and images of Australia’s birds and mammals to the whole world.

Gould was charmed by the delights he found in the Elizabeth Bay garden of Alexander Macleay, a Scottish entomologist who became the New South Wales colonial secretary and the first president of both the Australian Club and the Australian Museum. As well as the thousands of hectares of farmland that Macleay owned across New South Wales, he had built the ultimate trophy home – said to be the finest house in Australia, on 22 hectares at Elizabeth Bay.

It was in Macleay’s garden that Gould watched a pair of white-bellied sea eagles and had his first look at a live brush turkey strutting about among the chickens. The brush turkey was already the bane of suburban gardeners across the Australian colonies, but Gould was intrigued by the creature that had divided ornithologists over whether it was a vulture or poultry.

There was one bird, though, that Gould wanted to take in great numbers back to England. Long before he had left England, the explorer Charles Sturt had told Gould about the ‘betcherrygah’, or warbling grass parakeet.

While exploring the interior of NSW, Gould saw the sky almost filled with the little birds as he camped close to Breeza Station, near the present-day town of Gunnedah. He found them breeding in huge numbers in the hollows of the tall gum trees that grew on the banks of the Mooki River.

In the intense heat of a bush summer they sheltered, camouflaged by the green leaves, but in the cool of the evening, they swooped down in great chattering flocks to drink from the ponds near Gould’s tents, and then flew off just as quickly to feast on the grass seeds of the everlasting plains.

Gould was enthralled by their appearance and charmed by their personalities.

He documented the “betcherrygahs’” as “budgerigars” and said they were “the most amiable, cheerful little creatures that can be imagined.”

He took some back to England with him and his promotion of them helped the budgies to become one of the most popular pets in the world.

The budgies thrived, but sadly by the time the Goulds’ book Mammals of Australia was completed in 1863 many species of Australian wildlife were extinct or endangered, including the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger.

The Goulds’ drawing of a male and female thylacine remains an iconic image of a species now extinct.

Gould pushed hard for conservation of Australia’s unique wildlife. Of the koalas, Gould wrote that it would become scarcer because of the fur trade.

Thankfully, conservationists have rallied against his dire prediction that it would become extinct too.

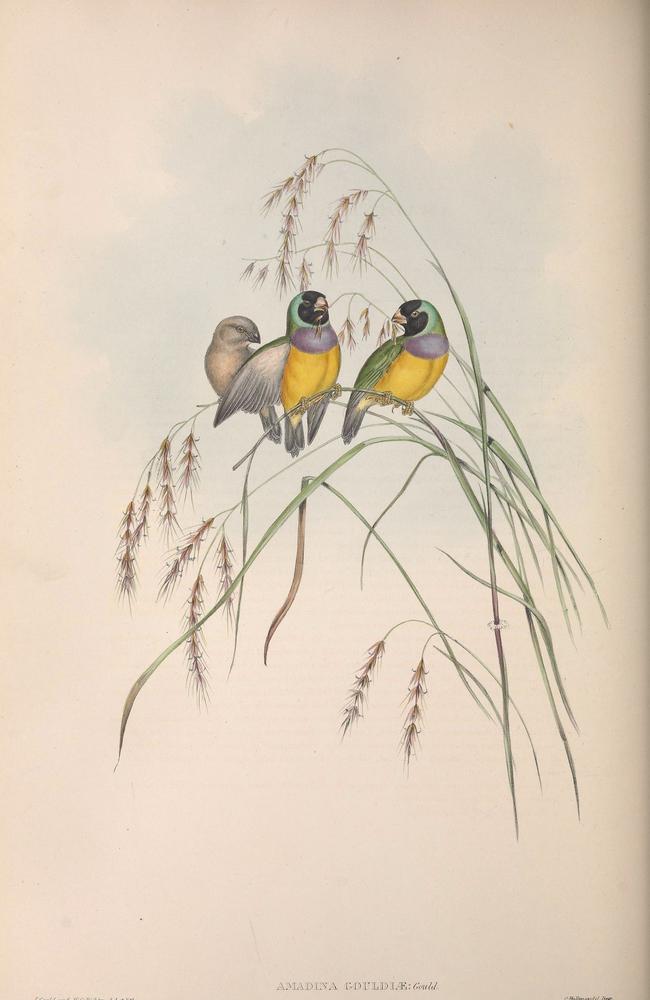

But many of the birds and animals the Goulds documented, including the sublime paradise parrot found along the Condamine River, no longer exist. Even the exquisite Gouldian finch which Gould named for his wife, is endangered.

The Goulds’ tireless documentation of Australian life remains the most complete record for many species that have sadly disappeared for all time.

The work of Mr and Mrs Gould is a testament to their passion, industry and achievements. It is also an enduring testament to what Australia had, what we have lost, and what we must strive to protect.

This is an edited extract fromMr and Mrs Gould by Grantlee Kieza is available now, published by HarperCollins/ABC Books. Read extracts from his other most recent book, Sister Viv, in the links below.

More Coverage

Originally published as King, koalas, conservation: The extraordinary story of John and Elizabeth Gould