‘Shock’ wages surge blows the budget

Wages growth over the year to the June quarter is going to approach 2 per cent, meaning it’s taken just one week after the budget for one of the key Treasury forecasts to blow up.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Can Treasury – the key economic advisor to government – really be that hopeless and so utterly clueless?

It’s taken just one week after the budget for one of the key Treasury forecasts to blow up. The budget was largely built on the assumptions of uncertain economic growth and sluggish wage growth and low inflation – hence the justification for the big-spending.

As Treasury head Steven Kennedy said Tuesday: this was not the time to embark on aggressive budget repair.

Specifically, Treasury forecast that wages growth over the current financial year which is about to end would be 1.25 per cent.

The official ABS data Wednesday tells us that we’ve already had the 1.25 per cent in the nine months to March. Wages growth would have to be zero in the June quarter for the Treasury forecast to be right.

There’s zero chance of that, with employers desperate to find workers, pretty much across the spectrum, and with skilled job vacancies hitting a near-13 year high.

Wages growth over the year to the June quarter is going to approach 2 per cent.

Now the difference mightn’t seem like much. In fact, it exposes Treasury’s complete inability to understand what’s been going on in the economy.

All through the December quarter and the first four months of this year, Treasury missed how strongly the economy was bouncing back, off the massive fiscal stimulus (JobKeeper especially) and the Reserve Bank’s zero interest rates. It was bad enough, although arguably excusable, that Treasury failed to see it coming ahead of time.

In the formal budget in October, it predicted the economy would shrink by 1.5 per cent in 2020-21 and the jobless rate would still be 7.25 per cent in the June quarter. Just two months later, in the December budget update, it had at least recognised that in fact the economy would grow, but only by a very marginal 0.75 per cent. But the jobless rate would still be 7.25 per cent in the June quarter.

By March, the jobless rate was already down to 5.6 per cent. Treasury clearly thought the economy would go over a (hopefully, small) cliff, and the ranks of the jobless would be flooded, when JobKeeper ended at the end of March.

That’s clearly proved not to be the case. Kennedy himself revealed Tuesday that only somewhere between 16,000 and 40,000 had lost their jobs when JobKeeper ended, not the 100,000 to 150,000 Treasury had “expected”.

The jobless figures for April from the ABS Thursday will tell us what happened. Now again, and this is the critical point, you could understand – and even, partially, excuse - gloomy forecasts, made before JobKeeper had actually ended.

But Treasury’s latest budget forecasts were made in early May. There is no excuse for not seeing what had been happening in the economy, and critically to jobs and to wages.

And maybe, most importantly, to emerging inflation. The big question posed by wages growing faster than Treasury expected is whether inflation as well as wages are accelerating faster than expected.

The whole basis of the RBA promising to keep its official interest rate at zero – and so the owner-occupied mortgage rate around 2 per cent – for another three years (at least) is no expectation of higher inflation any time soon.

Yet we’ve just seen inflation kick up to nearly 1 percent (0.9 per cent) in a single quarter in the US.

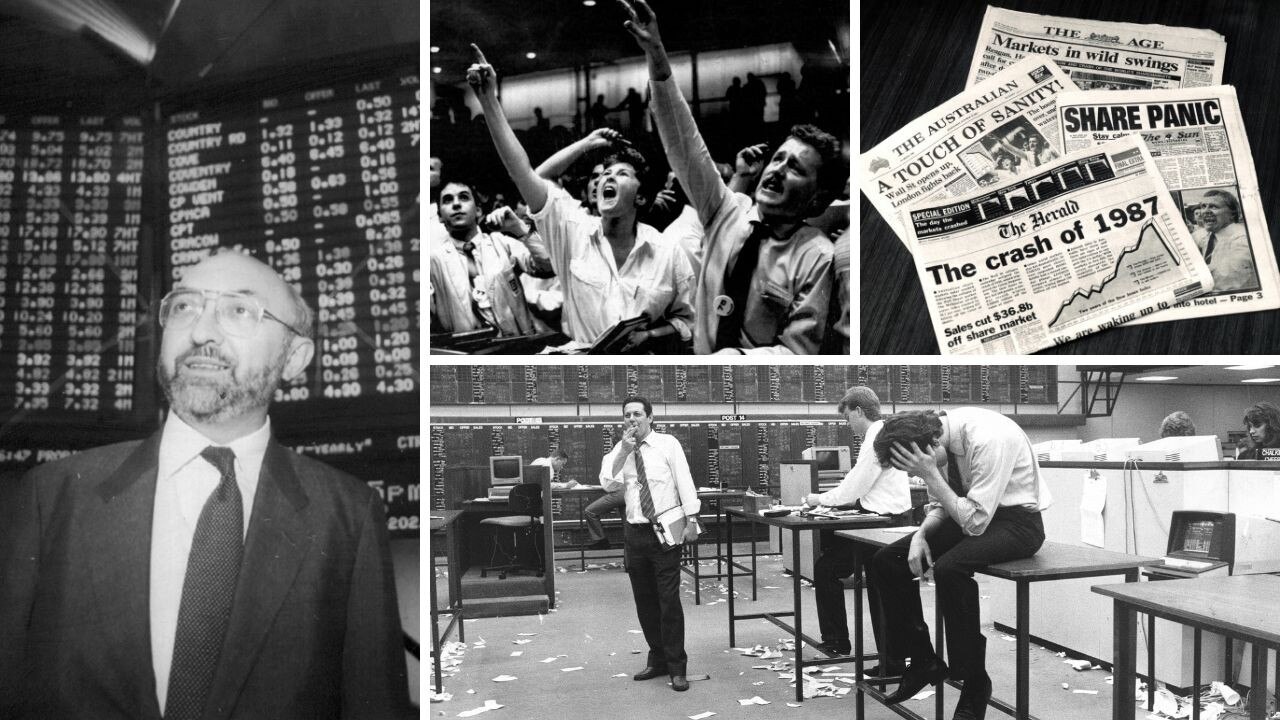

Former Treasury secretary Larry Summers has blasted the Fed for its “dangerous complacency” over inflation; as it’s also said it doesn’t see higher inflation in the US for at least three years. We are walking a knife-edge – in the US and here. An inflation shock would send market interest rates spiralling and the share market plunging.

At best, we will see more – unpleasant – days like we saw Wednesday.

Originally published as ‘Shock’ wages surge blows the budget