Whoever wins the US election, Australia will be up-ended and must learn to stand alone

On Tuesday, Australia’s place in the world will be changed forever. Experts warn we must drop the apron strings and find our own two feet.

Trump or Biden. Left or right. Rule of law or civil war. Whatever the outcome of the US presidential election, it will up-end Australia’s place in the world.

The international order has changed.

The United States is no longer the world’s sole superpower. It’s also losing interest in playing the role of world policeman.

That means uncertain times ahead.

“Every US general election carries implications for Australia,” says the University of Sydney’s professor Simon Jackman. “But many observers would insist that this time, it’s different.”

The Lowy Institute’s international security director Sam Roggeveen warns the next presidency will be little more than window dressing. The balance of power has already shifted.

“The problem is that whoever wins this US election will inherit a political system and a nation that have no appetite for a contest on the scale that would be required to contain China’s rise,” he says. “Experts tell us that Republicans and Democrats in Washington are united on the need to confront China, but how deep is their resolve?”

RELATED: Why Americans don’t want to vote

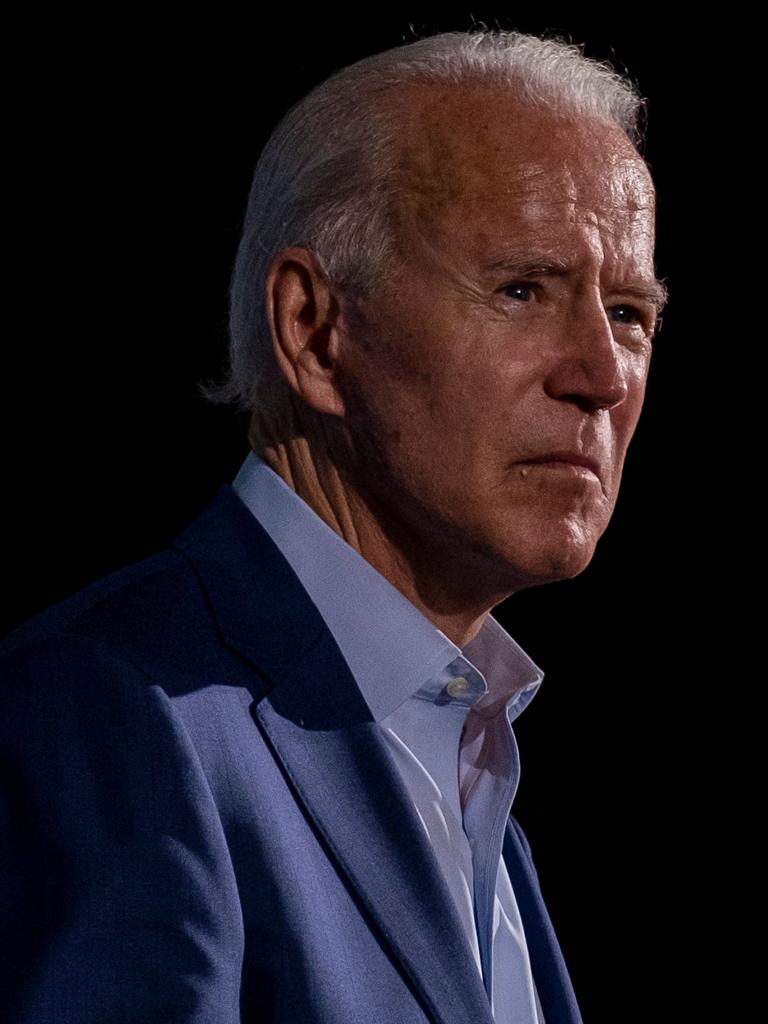

RELATED: Joe Biden’s long fight to take on Donald Trump

Brookings Institution foreign policy analyst Dr Thomas Wright says Australia’s future is in the hands of US voters.

“If the American people confirm their support for an America First president by giving Trump a second term, this (rules-based international order) system will break and be replaced by something else,” Wright says. “If Trump is re-elected, the rest of the world will conclude that the United States has fundamentally changed and the period of post-war leadership has ended.”

Biden, he says, isn’t necessarily in any position to change that.

“I think Biden is a believer in the romantic case for US leadership in the international order. So he believes in alliances, he believes in relationships, he believes in a values-based foreign policy. He’s been that way for decades.”

But Wright argues the United States Mr Biden would lead has fundamentally changed.

And US domestic issues always trump foreign policies.

THE RETURN OF TRUMP

“If (Trump) is re-elected, the only conclusion to draw will be that the American people want this new direction and that they are willing to trust the foreign and domestic policy of the country to him and with everything they know about him,” Wright told the Director’s Chair podcast.

“And my sense from talking to diplomats and other officials around the world is that they will basically conclude that the verdict is in. Whether or not the US leaves key alliances immediately, (they) have to prepare for that eventuality.”

RELATED: Odd way Biden fans helped his campaign

Professor Jackman, chief executive officer of the United States Studies Centre, says Australia may not face such a security crisis.

Canberra’s already taken sides in the new great-power competition. US Marines are now based in Darwin. Australian warships are participating in “freedom of navigation” operations in the South China Sea. Its diplomats are openly challenging Beijing’s behaviour. Its government is pushing back against interference in internal affairs.

As such, it may not suffer the same stress as the US relationship with Japan and South Korea. Not to mention the UN and NATO. But it will suffer the fallout.

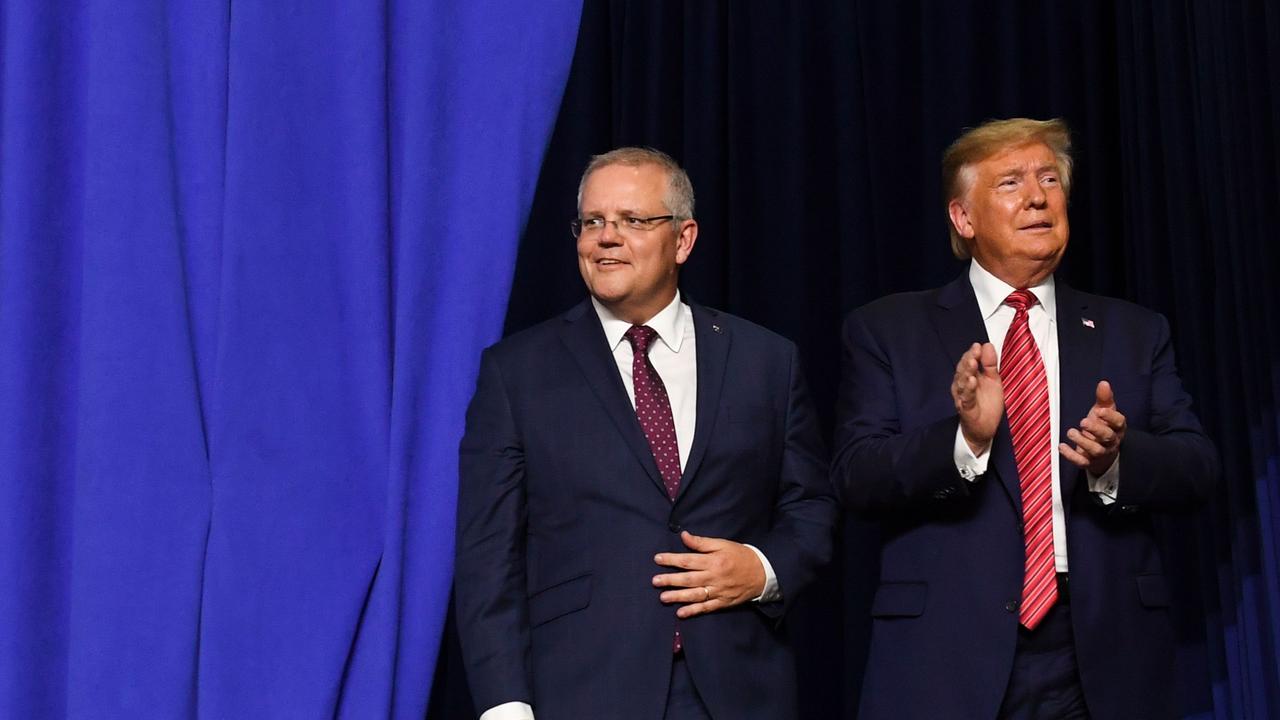

“Through deft and creative diplomacy and our ‘frontline’ position vis-a-vis China, Australia enjoys a close relationship with a sometimes unpredictable and unconventional Trump administration,” Jackman says. “(But) if Trump wins re-election – again, defying polls, pundits and his many critics – Trump and his advisers will understandably feel validated and emboldened.”

And that means his “America First” attitude will be reinforced.

Dr Wright is blunt. He argues US foreign policy is already in crisis. A second term won’t change that.

“There is no reason to believe that President Trump will follow in the tradition of other Republican presidents and pursue a more multilateral and cooperative strategy in his second term,” he writes.

“Emboldened and unconstrained, a second Trump administration could spell the end of the alliance system and the post-war liberal international order.”

IF BIDEN TRIUMPHS

Mr Biden hasn’t had a presidential first term. As such, his track record is not as straightforward as Mr Trump’s.

“Biden is an enigma,” Wright argues. “If he becomes president, his differences from Trump will not suffice as an organising principle for his foreign policy.”

While a Biden administration “would be a reprieve for the US-led international order”, it won’t be able to restore things to what they were.

“The question for Biden is not whether he will be different from Trump. That much is obvious. It is whether he will differ from president Barack Obama,” Wright says.

Things are different now. Biden will have to convince an inward-looking US public that it still has a place in the world.

The USSC’s Jackman believes Australia will likely lose the ‘most favoured’ status it tentatively holds with Trump. Under Biden, it will return to being “just one of many allies”.

“Australia’s alliance credentials and our ‘frontline’ status with respect to China are tremendous assets here,” he says. “But risks abound, with NATO partners understandably keen for a post-Trump reset of strategic US priorities … along with internal competitions for resources across the US government threatening to distract attention from the Indo-Pacific.”

The chaotic election campaign has been light on policy detail. As such, a multitude of questions remain about Biden’s plans.

Wright asks: “Will Biden continue down the path of great power competition with China and Russia? Will Biden take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis to introduce major reforms to the international order, and what will the content of those reforms be?

“Most important of all, can Biden set the stage for a renewal of American leadership, or will history remember his administration as a brief and futile last gasp?”

NEW WORLD ORDER

“Irrespective of the election outcome, an enduring legacy of the Trump administration is a resetting of the American strategic mindset: great power rivalry is now the singular external challenge faced by the United States,” says Professor Jackman.

China is openly challenging the post World War II balance of power while undermining international law. It is intimidating its neighbours. It is engaging in landgrabs in the Himalayas and East and South China Seas. It is stealing technology. It is hacking institutions. It is manipulating governments.

How the next White House administration responds to this will shape the world for decades to come.

“Both sides of US politics acknowledge that the magnitude and breadth of the China challenge can only be effectively met in partnership with allies. But this acknowledgment seems more foundational under a Biden administration,” says Jackman.

Under a second Trump term, Wright argues that partnership seems less certain.

“In Asia, the big question will be whether Trump sticks to his tough China policy or, with the election out of the way, tries to resurrect his trade deal with Xi while also pulling back from America’s alliances,” he says.

Both outcomes are problematic for Australia.

“America’s allies are concerned that it will preclude any possibility of co-operation with China … and that decoupling on the scale that some Trump administration officials envisage is impractical and costly for countries that rely on China economically.”

Wright says Mr Biden’s Democrats have a different approach. The party is considering a new international power bloc specifically intended to counter the autocracies of Chairman Xi and President Putin. America would base this alliance on promoting and strengthening the principles of democracy.

“This is not new,” Wright writes. “Proposals for a concert or league of democracies have been around for at least 15 years, but the Trump administration has given them new life.”

This has potential diplomatic benefits for Australia, as well as economic costs.

The Democrat Reformist faction wants “democracies to become collectively resilient, including partially decoupling from authoritarian countries. They want to work with other free societies to promote liberal norms and to compete with China and Russia in international institutions,” says Wright.

The Democrat Restorationist faction, however, doesn’t see democracy as being in crisis and “worry about creating an ideological fault-line in world politics that exacerbates competition with China”.

AUSTRALIA ALONE?

“Few countries enter the Washington post-election environment with as much goodwill. (This is) a position of strength that will serve Australia well under either election scenario,” the USSC’s Professor Jackman concludes.

“Australia is something of a unique case,” Brookings’ Dr Wright adds. “Along with Abe’s Japan, Australia has handled Trump better than any other liberal democracy, albeit after a rocky start with the terse phone call between then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Trump.”

Canberra has a trade deficit with Washington. It spends more on defence than Trump demands of his allies. It has also taken a firm stance against Mr Xi’s China.

But the ball is firmly in the court of the next US president when it comes to respecting the close relationship.

“The uncertainty around Trump’s commitment to maintaining the regional order in the Asia Pacific is a concern for Canberra about a second term, and only a third of Australians express confidence in Trump,” Wright warns.

Mr Biden is also an uncertainty.

“Democrats feel that there is much to learn from Canberra when it comes to tackling political interference,” says Wright. “They are also keen to deepen relations between democracies in Europe and Asia, and Australia will play a key role in that effort.”

The problem, however, remains China.

“The Australian government is likely to favour Biden taking a tougher approach to China than did the Obama administration. So it may find itself weighing into the restorationist versus reform debate,” Wright concludes.

But the Lowy Institute’s Roggeveen questions the resolve of any future US president.

The Cold War, he says, was won because the US convinced the world it had the principles and commitment to suffer a war – even a nuclear one – on behalf of its friends.

“The critical question for America’s adversaries and allies in Asia today is whether any of them would believe the same thing. Does the US still have that kind of resolve?” he asks.

“Despite the change in rhetoric in Washington, there is no sign that the US is actually gearing up for a struggle on that scale. Neither presidential candidate is promising to restore America’s military edge in Asia. No matter who is in the White House, Asia’s security system will evolve from one of American dominance to a balance of power.”

And finding that balance means tough times ahead for Australia and its region.

Roggeveen warns: “No matter who wins next month, Australia faces a future in which maintaining our security will increasingly be a job for us alone.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel