Donald Trump’s vote dispute is ‘blackmail’ says political scientist

President Donald Trump is legally challenging votes in key states and this is all part of a plan says a political expert. So what happens next?

The tension is explosive. The US tradition of humbly accepting the will of the people has been cast aside. But that’s a common outcome of close elections around the world. What has happened there may tell us what comes next.

Partisan politics. A pandemic. Civil unrest. The United States has split down the middle. And where statesmanship once maintained decorum, dogma has raised its ugly head.

Windows are boarded up. Walls have been built. Checkpoints are in place.

It’s not normal for the United States. But it is for disunited states.

RELATED: When we’ll know who has won election

RELATED: Can Trump really challenge US election result in Supreme Court?

Of 178 presidential elections globally between 1874 and 2012, 38 were disputed. Most of these sparked conflict and constitutional crises. Some resulted in a civil war.

According to political scientist Victor Hernandez-Huerta, that’s the price losing candidates are prepared to pay to win powerful concessions – if not power itself. “I call this the ‘blackmail strategy’ of losing parties and candidates: losers threaten to up-end post-election stability unless they receive benefits,” Dr Hernandez-Huerta said.

But it comes at a hefty price.

Universal College London political analyst Nadia Hilliard warns democracies live or die on the perception of legitimacy.

“Whatever the outcome, significant parts of the US would see their new leader as illegitimate. Regardless of whether Trump or Joe Biden is ultimately inaugurated as their 46th president, millions of Americans will see the outcome as ‘the end of democracy’,” she said.

RELATED: Are Trump’s voter fraud claims true?

And there’s an explosive new ingredient in the mix: COVID-19.

The pandemic, analysts say, has set the election on a tinderbox of immense fear and uncertainty. Life. Death. Ways of life. All have already changed – for the worse.

ANGER IN THE AIR

Fox News presenter and outspoken Trump ally Tucker Carlson said the mood in Manhattan and Washington after the election was “distressing”.

“We are in a different place, and what I’m struck by is how readily and passively we’ve accepted it,” Carlson told his audience. “This is a courageous country full of courageous and decent people. Why would we put up with the assumption we need to hunker down and protect ourselves from violence?”

That assumption, says Dr Hernandez-Huerta, is based on public perceptions of crisis. And candidates often seize on the idea of electoral flaws and fraud to motivate their followers. Their motives can be pure. Or not.

“Those who challenge election results under such circumstances likely aim for something other than electoral reform,” he writes.

According to Universal College London political analyst Nadia Hilliard, such manufactured crises damage democracies to their core.

“The apocalyptic tenor of the election reflects deeper, foundational challenges to the legitimacy of American democracy of which Trump is a symptom more than a cause,” she writes.

While election day itself was virtually free of violence, tensions are set to be further inflamed by allegations of voter fraud. And an out-of-control pandemic taking an ever-increasing toll on the economy and morale of the nation.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley believes the threat of violence remains very real. So real he took the unprecedented step of publicly vowing the enormous US federal military would not get involved. Nor would it take any action over who does – or does not – move into the White House.

ALL’S FAIR IN LOVE AND WAR?

The key to democracy isn’t just the rule of constitutional law. It’s the graciousness of its people and the statesmanship of its politicians to accept defeat. After all, unlike monarchies, dictatorships or single-party states, they’ll get another chance at power in just a few years.

“After votes are freely cast and fairly counted, the losing candidate or party accepts the results as legitimate and concedes to the winner,” Dr Hernandez-Huerta writes. “US President Donald Trump has threatened to up-end this tradition.”

Precedents of what to do in these troubling scenarios have been set.

It’s happened several times before in the United States.

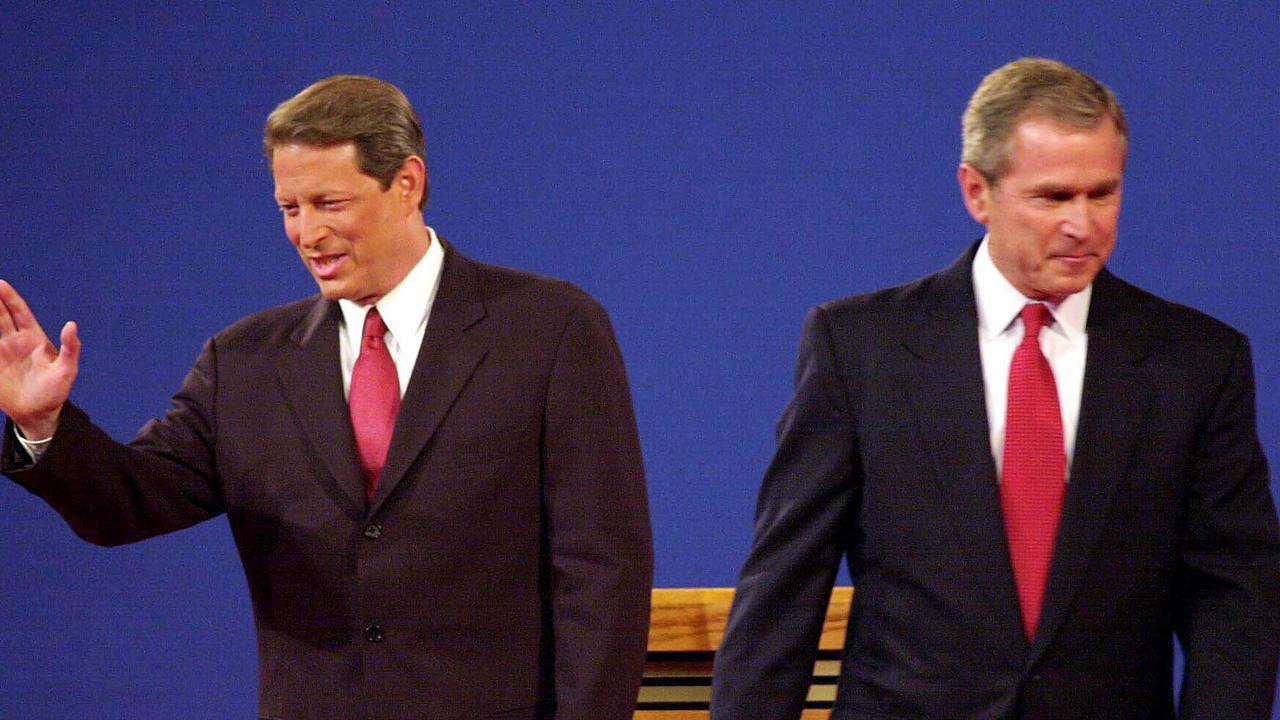

Most recently, Democrat candidate Al Gore challenged the outcome of the 2000 election. The deciding state was Florida. That state was governed by the brother of his electoral opponent, George W. Bush.

The outcome hinged on a few dangling pieces of paper in what should have been punch-holes – disparagingly dubbed “hanging Chads”. The Republican-dominated Supreme Court ordered the recount be stopped. Instead of pressing the issue, Mr Gore declared: “For the sake of our unity as a people and the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession.”

But times have changed. Things are different in terms of national mood and political dogma.

“A disputed presidential election would take the United States into uncharted territory,” Dr Hernandez-Huerta warns. Given the enormous potential risks, why are losing presidential candidates so often willing to brush aside democratic tradition and reject unfavourable electoral outcomes?

He says political science offers a potential answer: “Blackmail”.

DEEP ANXIETY

The coronavirus pandemic was central to the presidential campaign. Mr Biden made its management a significant issue. Mr Trump made dismissing it a regular feature of his maskless public appearances.

But the virus doesn’t care about politics. It has just one goal: to reproduce. And it’s winning. Big time.

There have been about 10 million cases in the United States and 240,000 deaths. Those numbers continue to accelerate upwards. The eve of the election recorded 93,000 new sufferers alone.

Like unemployment, sickness and death are rapidly becoming dramas for all US families.

And, analysts say, voters have reacted with a mix of anxiety, faith and outrage.

Mr Trump insists the virus would disappear “like magic”. Mr Biden points to the numbers and says, “I told you so.”

But COVID’s impact is measurable outside the ballot box. Economic uncertainty is soaring. Public confidence is plummeting. Businesses are bracing for bad times ahead.

Voters are already suffering COVID-induced cabin fever.

And many of those voters are packing heat after an extraordinary gun-buying frenzy amid widespread scenes of civil unrest.

“I think you have a fear among a good percentage of Americans that something bad could be coming,” says University of Illinois Springfield criminal justice professor Ryan Williams. “And they don’t know what that is. They don’t know what that looks like.”

MANUFACTURING CRISIS

American voters know there is a problem. They disagree on what it is.

“While polarisation is hardly a novel feature of the American political landscape, the reluctance to accept one’s opponent as legitimate is new,” Dr Hilliard writes. “This challenge to a shared sense of legitimacy strikes at the very core of the country’s democratic framework.”

All branches and levels of government are under stress. Norms have been cast aside. Individual authority is being exerted in the place of competence and consensus.

But, most importantly, the concept of remaining loyal to democracy above loyalty to one’s party has been eroded.

Accountability. Transparency. Debate. Compromise. When exercised within a democracy, these give losing parties a powerful say – and hope they may convince swinging voters to their way of thought at the next election. It’s called “loyal opposition”.

Take them away, and it becomes a clash of immovable dogmas.

National stability and security are weaponised. Concessions are demanded. In worst-case scenarios, coups are initiated.

“When the rules underlying the basic institutions upon which a democracy rests are flouted and rewritten, the basis for loyal opposition is undermined for both sides,” says Dr Hilliard.

“And though the partisan jibes that eroded a sense of loyal opposition preceded Trump by decades, his presidency has forced a radical question for all: will I accept the outcome if my opponent wins?”

ART OF THE DEAL

Not all presidential crises are coups.

“Losers reject unfavourable election outcomes in order to strengthen their post-election bargaining positions and extract political concessions from the winners,” says Dr Hernandez-Huerta.

One recent example is Indonesia.

Megawati Sukarnoputri lost the vote by a massive margin – some 34 per cent. But the outcome was contested. Court cases were initiated. Significant concessions were won from the new government in exchange for a peaceful transition.

The scene is set for just such a transaction in exchange for the White House.

“The United States has a long tradition of peaceful and democratic transfers of power, but it is not immune to electoral blackmail. If Trump loses, he may opt for the same self-serving playbook that 21 per cent of losing presidential candidates have followed over the last four decades – sacrificing the country’s political stability for his own political gain,” warns Dr Hernandez-Huerta.

Since early in the year, mail-in ballots have been the target of claimed “problems and discrepancies”. That priming of the public psyche is now bearing fruit.

“In other words, there is reason to fear that the President or members of his party might hold the country’s political stability hostage in an attempt to extract concessions from the Democrats,” he predicts.

What do the Republicans so desperately want that they’d risk national stability?

Why would the Democrats dig in their heels in the face of immense COVID-induced tensions?

“One possibility would be (a demand) the Democrats refrain from packing the Supreme Court in response to Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s rushed appointment,” Dr Hernandez-Huerta writes. “Such a concession would preserve an important part of Trump’s legacy and ensure that the court remains ideologically conservative for years to come.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel