ISIS and al-Qaeda battle for hearts and minds of radicalised Muslims

THEY were born in the same cradle of extremism, but Islamic State and al-Qaeda are at war. And it’s not good for us.

THE battle to capture the hearts and minds of radicalised Muslims is intensifying, with experts linking the recent terror attacks in Paris and Mali to the growing rivalry between Islamic extremists.

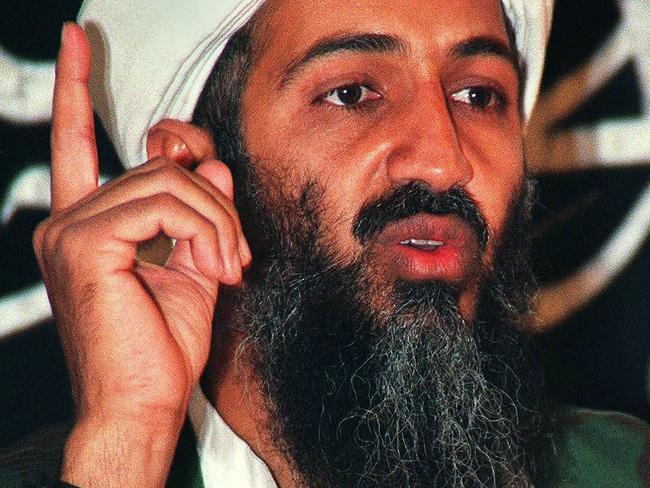

Before the Islamic State rose in influence, al-Qaeda was the world’s most feared militant group. We all remember its most horrific accomplishment, when a hate-filled campaign against the West culminated with the 9/11 attacks on US soil.

But in recent years IS, with its brutal beheadings and social media savviness, has become the organisation of choice for extremists, even though it still isn’t the deadliest (that title belongs to Boko Haram).

This surge in the Islamic State’s profile has led to increased tension between it and al-Qaeda.

IS once operated under al-Qaeda in Iraq, but officially split from the group in 2013 to pursue a different strategy in Syria.

Since then, it has carried out gruesome assaults on “infidels”, killed thousands of Muslim civilians and amassed a frightening following - a following which appears to have annoyed al-Qaeda.

SAME ENDS, DIFFERENT MEANS

Both groups have the common goal of ending Western influence in the Middle East. The main difference between them is their tactics.

Al-Qaeda initially framed its attacks on the West as a response to US foreign policy, believing that could unite Muslims behind its cause. It has since sought to ally itself with insurgents in post-Arab Spring countries.

The Islamic State, meanwhile, immediately started to seize territory and stamp out anyone in its way, including thousands of Muslim civilians, which it has been criticised for.

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s proclamation of a worldwide caliphate last year, in which he also annointed himself leader of all Muslims, added to the tension. It led to a war of words between al-Baghdadi and al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri.

In September this year, al-Zawahiri hit out at the self-declared Fourth Caliph and his followers, accusing him of “sedition”.

“We have endured a lot of harm from Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his brothers, and we preferred to respond with as little as possible, out of our concern to extinguish the fire of sedition,” al-Zawahiri, an Eygtian doctor, reportedly said.

“But Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his brothers did not leave us a choice, for they have demanded that all the mujahideen reject their confirmed pledges of allegiance, and to pledge allegiance to them for what they claim of a caliphate.”

DEADLY ONE-UPMANSHIP

In a bid to keep up its profile, al-Qaeda’s Yemen affiliate launched the attack on the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris in January, sparking global outrage.

According to The New York Times, European analysts believe the mastermind behind the recent Paris attacks saw the Charlie Hebdo assault as a challenge to carry out something “bigger”.

And experts believe the atrocity in Mali, for which al-Qaeda claimed responsibility, was a message not just to the West, but to the Islamic State. Al-Qaeda wants everyone to know it’s still capable of causing murder and mayhem.

“All the attention has been focused on the Islamic State, Iraq, Syria and threats to the West,” former MI6 agent Richard Barrett told The New York Times. “The guys in Mali saw a big opportunity to remind everyone that they are still relevant.”

Professor Yehudit Ronen, from Bar-Ilan University, toldThe Jerusalem Post that while the attack in Mali was an indication of the rivalry between IS and al-Qaeda, it should also been considered in the context of the region.

“The Mali attack demonstrated that the ongoing conflict there is a main focal point of the interconnected ongoing Islamist insurgency stretching across North Africa and the Sahel environs, particularly neighbouring southern Algeria, Libya, and Egypt,” she explained.

“The attack in Mali should be examined not only within the context of the prestige and power rivalry between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State but also within the ongoing simmering ethnic-political and socio-economic tensions in Mali, as well as within the context of the negotiations between the northern Mali rebels and the government.”

But Djallil Lounnes, an expert on radical groups in the Sahara who is based in Morocco, told AP it was carried out to remind the world that the movement founded by Osama bin Laden had not been completely eclipsed by the Islamic State and its self-styled caliphate.

“Al-Qaeda and its international affiliates have been surpassed by IS and needed to show that they are still there,” Mr Lounnes said.

DIRECT CONFLICT

As pressure to outdo each other intensifies, IS and al-Qaeda are clashing directly in the battle over southern Syria. The latter reportedly took out a key IS militant, Muhammad “Abu Ali” al-Baridi, in a recent suicide bombing.

Al-Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, took credit for the attack on Twitter, Fox News reported.

But while there is bitter infighting between the two Sunni Muslim terrorist groups in southern Syria, counterterrorism expert Clive Williams from the Australian National University told news.com.au there is not an all out war... yet.

He explained that while there were some distinct ideological differences, it was not in their overall interests to wipe each other out.

“The Islamic State is essentially an Iraqi group,” he explained. “Its main focus has always been on the caliphate, Syria and Iraq. Of course it’s got foreign fighters, but its focus is Iraq.

“The only fighting that I am aware of between them is in Syria and Libya. I don’t know of any fighting between them going on elsewhere.

“Essentially, al-Qaeda has certain areas of influence like the Arabian peninsula, Islamic Mahgreb and so on. Islamic State has got nowhere near as much influence in those areas.

“I don’t think they naturally get stuck into each other, I think they are prepared to tolerate each other because it’s not really in their interests to be fighting each, other except maybe in Syria, because there are seen as traitors there. Elsewhere I think the two, generally speaking, are doing their own thing and ignoring each other.

“There is a leadership tension between Zawahiri and Baghdadi and in particular over Baghdadi declaring himself the Caliph. That obviously hasn’t gone down well with al-Qaeda, but I don’t think that situation is what really caused them to have problems at a working level.

“I don’t think the Islamic State wants to fight with al-Qaeda and I think the same with al-Qaeda. Sometimes there are local tensions with local warlords and egos. I would say if one became too dominant, the other might want to do something about it, but I don’t think they are at that point.”

Not yet, at least.