‘Under assault from every angle’: Chilling threat facing the West

Forget submarines, ships and stealth fighters — warfare has changed irrevocably. And the West is being caught completely unawares.

War isn’t about submarines, ships and stealth fighters anymore. Those are the weapons of a bygone age. Instead, the new battlefields are truth, trust, information — and plausible deniability.

It is a clash of cultures. An invasion of ideals. A manoeuvring of one set of morals against another.

It’s a new kind of battle being fought right now on the “hearts and minds” of Hong Kong.

It’s a grey war being fought in the shadows of social media, economics, trade and diplomacy.

It’s a war without rules.

President Putin’s Russia has been waging this war now for decades. He’s made more advances than the Soviet Union ever did. Moscow’s exploitation of misinformation, along with cyber attacks and troops not flying their national flag have given him Georgia, Crimea, eastern Ukraine and Syria. Now it’s doing the same in Venezuela.

China has noticed. Its cyber attacks have boosted Beijing’s military technology to rival that of the US. Its unilateral actions are undermining the entire concept of international law. It “owns” several minor governments through debt traps. And its unofficial mercenaries — fishing fleets — are seizing and holding new territories.

But there are also unexpected players: Mercenaries, lobbyists and social media “troll farms” hired by some of the world’s biggest corporations.

How can Western democracies fight back?

“Warfare has changed, but we have not,” US National Defense University strategist Dr Sean McFate challenged a recent Carnegie Institute gathering. “Our adversaries grasp this, and that’s why they prevail.”

So what is this “new war”?

FIRST LINE OF DEFENCE

On June 26, a large group of high-profile international academics, ambassadors, politicians, military and industry representatives quietly gathered in Adelaide.

They crowded into the Flinders University’s function room in Victoria Square. At the top of their minds was one driving concern: The survival of democracy in an increasingly chaotic era.

They were there for the launch of the Jeff Bleich Centre for the US Alliance in Digital Technology, Security and Governance. The theme was Democracy in the Digital Age: New Frontiers of Power and Trust.

From the words of those who spoke from behind and in front of the podium, it may have been titled “Survival of the Fittest”. And the daunting task of this new assembly of academics is nothing less than saving our way of life.

“Democracies depend on optimism,” former US ambassador to Australia Jeff Bleich told the gathering.

But that optimism is being deliberately eroded, he warned. From within, and without.

The end of the Cold War did not create the utopia the West expected.

“The autocrats did not disappear. They simply found new tools and a new path to restoring autocracy. Even worse, they see (a) new brand of capitalism as an opportunity for revenge,” Mr Bleich said.

“They’ve distorted capitalism — one of the most powerful tools of democracy — to fracture our democracy.”

TRUTH BOMBS

The West’s military might remain unassailable for the time being. But is that enough?

“Who cares about the sword if you can manipulate the arm that wields it?” asks Dr McFate, himself a former paratrooper. “This is how you win in modern warfare: not with tanks, it’s with ballot boxes.”

And Mr Bleich identified that battlefield as truth and trust.

“Because democracies rely on people making choices, the most important commodities we have are truth and trust,” he stressed. “We need to have accurate information, information that we trust, to make decisions. To make our choices.”

Which is why information is under constant assault from every direction.

“Democracy is uniquely vulnerable to this type of attack,” he said. “In a totalitarian country, people do not get to choose, and they are denied information that would let them make good choices.

“In a democracy, the public is supposed to choose; but they can’t if they don’t know what is true. They can’t if they don’t know who to trust.”

Such is the power of disinformation.

All a state or corporate sponsored troll farm, hacker or digital saboteur needs do is implant a seed of doubt. Dispelling that doubt takes immense effort — and openness — on behalf of institutions and experts.

“Which is why disinformation campaigns work, why hacking voting systems works,” Mr Bleich said. “Because if you can’t trust the facts on which you vote, or that your vote even counts, then you are at risk of becoming autocratic.

FOREVER WAR

Dr McFate, who tackles the broad subject in his book Goliath: Why the West Doesn’t Win Wars, says aspirations for a “rules-based order” governing the world are in retreat.

“What’s left in its wake? No, it’s not anarchy,” he said. “But it’s a world where conflicts do not resolve. They persist and smoulder eternally in so-called ‘forever wars’.”

And these wars are not about bombs and bullets — though they certainly are often a feature. They’re about influence. Information. Profit. Power.

“Those who grasp the changing global environment of durable disorder can exploit it. Those who do not are being exploited.”

Forget Pearl Harbor. The fighting techniques of World War II no longer apply.

This new war is being fought by powerful nation states. But active participants include terrorist organisations, international criminal cartels, unscrupulous business empires, and motivated interest groups.

The victors in the new battle space are those who inform — or distort — public opinion.

So what are the most significant threats the West faces?

“You could say China, Russia — those are the threats du jour. It could be Iran’s missile program. It could be ISIS 3.0. It could be narcotic wars … it could be Venezuela … North Korea … genocide … climate change.

“Those are all bad threats. They are not the worst.”

Instead, it is the return of the very state of disorder that helped spawn democracy in the first place.

“If you look at the Middle Ages or early Renaissance, it looks very similar to today,” Dr McFate says. “The Middle East looks very much like this now … where you have anybody who is rich enough can wage war for any reason they wanted.

“And what this meant was there was persistent never-ending conflict.”

CLASS WARFARE

It’s a notion echoed by Mr Bleich.

“When the Berlin Wall fell, we declared victory,” he told the Flinders University launch. “Democratic capitalism had proved it was the most effective form of governance. Autocrats would eventually disappear, their people would choose our form of democratic capitalism, and we’d all receive a peace dividend.

“But that isn’t quite what has happened.”

Mr Bleich said the first mistake Western cultures made was to simply assume the newly democratic and capitalist nation states would adopt “long-term, win-win capitalism”.

“In fact, they developed their own, more brutal and less democratic form of capitalism,” he said. “And they exported it. Autocrats have reappeared using this tool of democracy, to actually fracture our faith, and destabilise our democracies.”

Another mistake was assuming the motives of those within newly “opened” societies were noble.

“Their entrepreneurs had been locked up in brutal autocratic systems,” Mr Bleich said. “They didn’t trust the future. They needed to horde and hide their money. They distrusted any kind of government regulation. They were schooled in the tactics of authoritarians. And they were hungry.”

Dr McFate argues this adds a whole new theatre to commercial competition.

“Today, we are seeing the return of mercenaries for the first time in 150 years,” he told the Carnegie gathering. “They went underground, but now they’re coming back. And these are not just the lone guys in the Congolese jungles with a Kalashnikov (rifle), these are high-end Special Operations units. These are showing up with attack helicopters.

“Now they have mercenaries, anybody who is rich enough can wage war for whatever reason they want, no matter how petty, the super-rich can become a superpower for good or for bad.”

And mercenaries offer a uniquely powerful weapon: plausible deniability.

SHADOW WAR

“Everybody thinks that if there’s going to be a big fight with China or Russia, that’ll be just like World War II … just with better technology,” Dr McFate said. “It won’t. Conventional war is dead.”

Which is why he says he simply cannot understand why Western governments insist on sinking tens of billions of dollars into weapons — such as stealth fighters and submarines — designed to fight on an obsolete battlefield.

“So what does new war look like?,” he asks. “Endurable disorder. A new type of global environment. A new type of conflict. It’s getting sneakier. War is getting sneaky.”

It’s also not black-and-white.

It’s about the entire scale of grey in between.

Take China’s expansion into the South China Sea.

“They get right in between that space of war and peace,” Dr McFate said. “They go right up to the brink of war in the South China Sea, right up to where we will react — and they stop. But they keep everything they capture or create. And this is how they’re winning the South China Sea, one island at a time — without carrier battle groups.”

New warfare is also seen in Crimea.

Russian Special Forces troops took off their badges and flags. State-backed mercenaries such as the Wagner group were deployed. They reinforced fake pro-separatist movements within eastern Ukraine — a cause promoted through co-ordinated misinformation campaigns.

“(Russia) used a lot of propaganda and information warfare,” Dr McFate said. “They occupied eastern Ukraine and Crimea with a ghost occupation. And the reason this works is that we live in a global information age where plausible deniability is more powerful than firepower.

“The Kremlin gets that. We do not”.

CODE WAR

One of the West’s worst miscalculations, Mr Bleich said, was assuming that global communications and technology would automatically promote democracy.

“What we have learned is that nothing is inevitable about these technologies,” he said. “Like any other tool, they can serve us or harm us. A hammer can build a house or break a skull.

“And so, nearly 30 years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, our nations and our allies need to reassess how to manage technologies to restore trust, and faith, and optimism.”

The optimism of the internet was boundless. eBay and Amazon linked producers to customers around the world. Twitter and Facebook allowed friendships to spawn across borders quickly.

“Nations like ours imagined how technology would be used to spread not just prosperity, but the two most important ingredients of democracy — truth and trust,” Mr Bleich said.

And it did. For a short time.

The uprising of oppressed peoples in the Middle East — dubbed the Arab Spring — was a direct result of the new-found power of social networking.

“But there was one group that took a different lesson from the Arab Spring,” he said. “Autocrats and other repressive regimes. They saw the existential threat to them immediately. But they also saw something else. They saw opportunity.”

Which is why the cyber threat isn’t so much about viruses or hacking.

It’s about influence.

“They realised that if a disorganised, unsophisticated, and under-resourced rabble in Tunisia could topple an iron-fisted leader with social media, imagine what a powerful, organised, wealthy and ruthless authoritarian with all of the levers of government at his disposal could do,” Mr Bleich said.

That imagination has long since been turned into reality.

“With digital technology, authoritarians could use the very tools of democracy — its freedom, its openness, its voting systems, its entrepreneurship, its innovation, its trust — to undermine democracy,” he said.

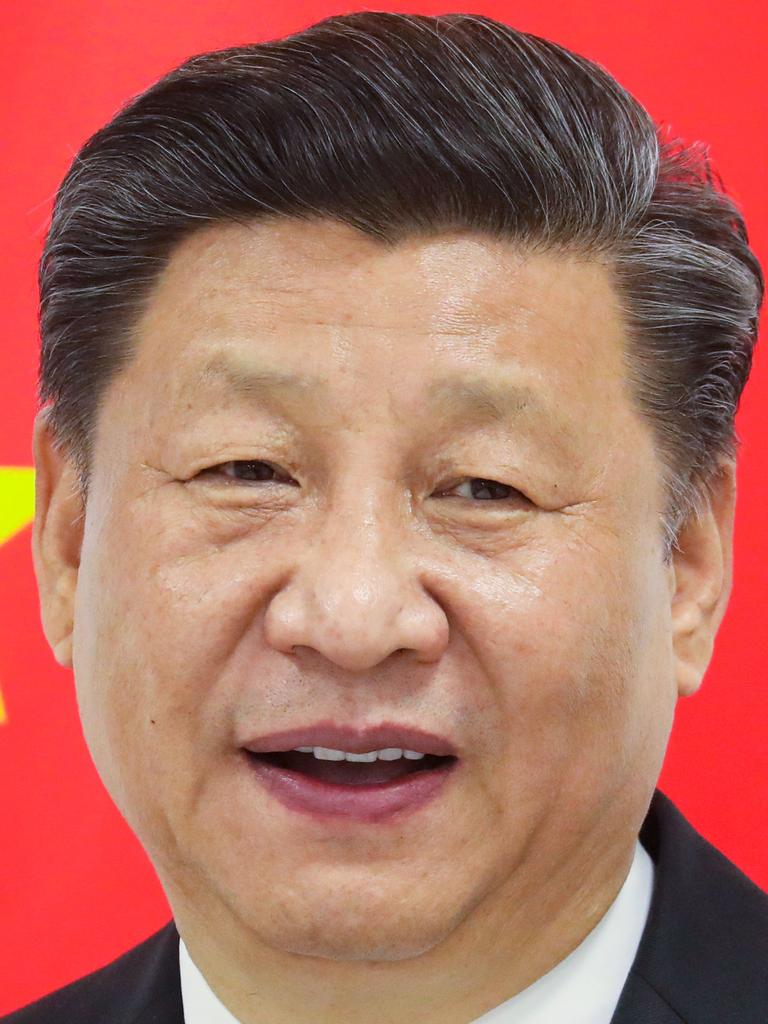

Autocrats now rely on disinformation: it has been the weapon of choice for Vladimir Putin in Russia, Xi Jinping in China, Kim Jong-un in North Korea, Hassan Rohani in Iran, Recep Tyyip Erdogan in Turkey, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

“They use digital technology not only to control their own populations. They use it to disrupt ours,” Mr Bleich said.

FREEDOM FIGHTERS

“In the future, victory goes to the cunning and not the strong,” Dr McFate said.

Similarly, Mr Bleich wants his Digital Technology, Security and Governance research team to be clever.

He told the launch it was time for Western democracies to do what they did best: Develop new agreements and treaties alongside openly enforced rules and regulations.

“(These must) protect the integrity of information, to prohibit commercial espionage, to punish hackers, to protect voting systems, to prevent the abuse of good technologies for bad purposes, to protect citizens from censorship and surveillance, to create international norms regarding kinetic cyber-attacks …” Mr Bleich said.

“Our tools will be identifying threats, developing norms, and recognising technologies that will protect us.”

Dr McFate offered some alternatives. Authoritarians, he says, are themselves vulnerable to destabilisation. In particular, paranoia.

Shadow war can be a double-edged sword.

“In some ways, autocracies are easier to destabilise because they centralise everything in a certain elite class. And if you can get inside that and create paranoia, the autocrat will take care of it for you — they will purge themselves,” Dr McFate said.

But is the West ready — or willing — to fight in the shadows?

Despite the enormity of the pressure democracy faces, Mr Bleich remains optimistic.

“This is not the first-time nations have faced this type of threat,” he said. “Throughout history, technologies that were originally developed to help bring people together and promote democracy — like ships and aeroplanes — have been transformed into weapons to attack us.

“Printing presses produced leaflets full of fake news. Radio broadcasts from Tokyo Rose peddled propaganda. We have seen this movie before.

“And each time we found a way.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer. Continue the conversation @JamieSeidel