The horror of Lockerbie: When Pan Am Flight 103 exploded

The horror of the Lockerbie explosion, when Pan Am Flight 103 blew up in the UK’s deadliest ever terror attack, lingers on 30 years later.

It remains the deadliest terror attack ever on UK soil.

The peaceful town of Lockerbie, Scotland, which lies 120km southwest of Glasgow, still carries the scars of an horrific plane crash, thirty years later.

It was December 21, 1988, when Pan Am 103 exploded above the small village, killing 270 people, including 11 people on the ground.

More US civilians died in the crash than any other terrorist attack (until September 11) – out of 270 people, 189 were American.

This led to suspicions that Libya, at that time heavily in dispute with the US, was involved in the bombing.

But it would be years before the truth was finally revealed.

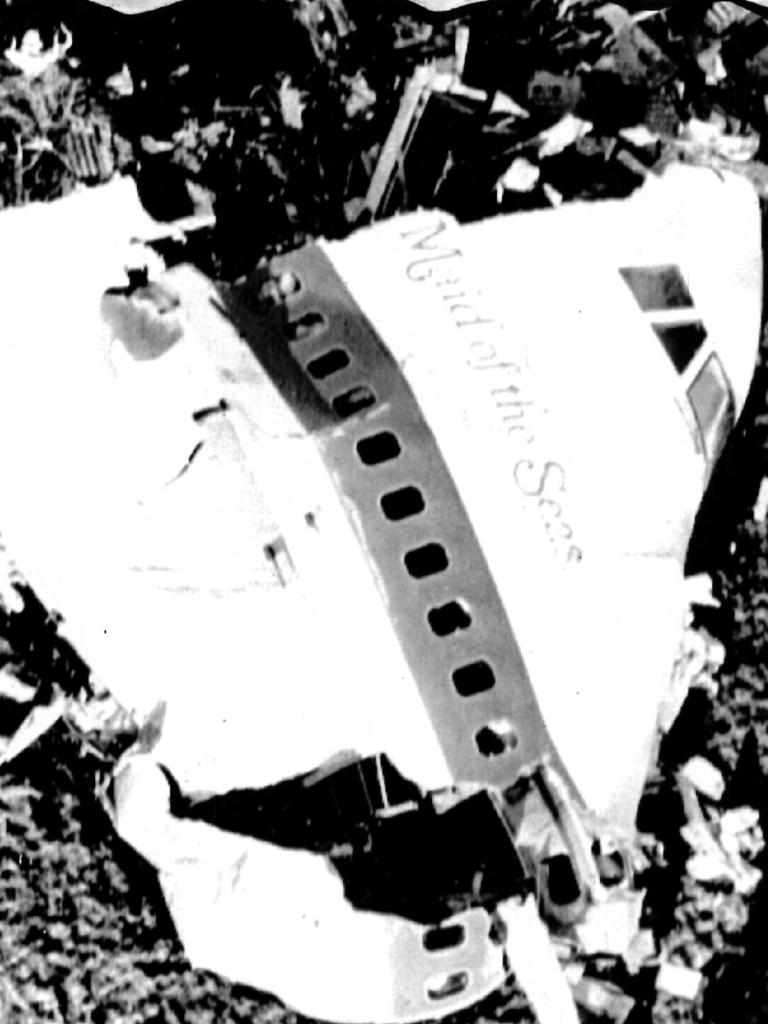

Witnesses describe the aftermath of the crash as a war zone. Even three decades later, the crash site photos are still absolutely shocking.

There have been years of scandal and conspiracy theories: relatives of the victims have long claimed they’ve endured years of having their phones bugged and that the investigation into the crash was botched.

But one thing was for certain, the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 was an act of terror.

It was four days before Christmas when a bomb in the cargo hold of the Boeing 747-121 exploded over Lockerbie, around 9pm local time.

While the plane was too high for anybody on the ground to hear the explosion, the town was soon hit by hundreds of large pieces of metal, thousands of pieces of debris, including the heartbreaking sight of Christmas presents.

And, most devastating of all, there were 259 bodies.

The wreckage landed in an area covering 2,200 square km, destroying 21 houses. Homes that weren’t flattened had their roofs torn off, windows and doors shattered.

According to Alan Dron, then a reporter for The Scotsman newspaper, Lockerbie residents told him they heard a sound similar to the roar of thunder that turned into a deafening roar. Then a flame-trailing chunk of wreckage from what two minutes earlier had been a plane smashed into the ground like a meteorite.

Dron wrote: “Seconds later, the wings, containing almost 200,000 pounds of fuel, crashed vertically into Sherwood Crescent, a row of bungalows, and ignited upon impact. Some residents’ bodies were never found, obliterated by the conflagration.”

The plane had gone off radar just 38 minutes after takeoff from London, just as it was about to begin the oceanic part of the route: Frankfurt to Detroit via London and New York.

Air traffic controllers later reported that pilots from other planes were alerting them to the sight of fireballs.

As the aircraft reached a height of approximately 9,500 metres, a timer-activated bomb detonated. Constructed with the odourless plastic explosive Semtex, the bomb was cleverly hidden in a cassette player inside a suitcase.

Nobody suspected that the unaccompanied suitcase would soon cause mass devastation and years of international intrigue.

Residents living in the quiet village of Lockerbie were directly in the path of the falling aircraft debris. It was a cold and windy night, with most residents at home, many watching Christmas specials on TV or wrapping presents.

As the largest section of the plane fell onto houses below, the explosion created a 47-metre-long crater that sent a massive fireball into the sky.

Witnesses described the blast as looking like the ‘mushroom cloud’ from an atomic bomb. As pieces of the aircraft fell on Lockerbie, dozens of fires broke out. Eleven locals were killed, ranging in age from 10 to 82.

The scene was described by many as “hell on earth” was of a wall of flames, the smell of kerosene, flattened homes and bodies strewn across the neighbourhood and nearby fields, on pavements and on top of roofs.

One Lockerbie resident described a neighbours’ house that was completely crushed as looking like “an enormous hammer had pounded through the roof”.

Among the wreckage was four Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A motors that were still going at full speed when they landed on the ground.

For the residents of Lockerbie it would be several hours before they realised it was an aircraft that had exploded and crashed upon the town, killing 11 people instantly.

In the aftermath of the crash, investigators found a timer, as well as fragments of a circuit board – evidence that a bomb caused the plane to explode and not mechanical failure.

Now the hunt was on for the bombers. But it wasn’t long before fingers were pointed at Libya.

THE LIBYAN CONNECTION

In March 1986, tensions between the US and Libya had reached fever pitch when the two fired at each other off the Libyan coast, in disputed waters.

Weeks later, in West Berlin, a bomb exploded at a nightclub filled with US serviceman, killing two Americans and a Turkish woman. More than 200 others were injured.

Once the US received intelligence that Libya had been involved, they responded with air strikes. Then US president Ronald Reagan said, “We believe that this pre-emptive action will not only diminish Muammar Gaddafi (Libyan leader) capacity to export terror, it will provide him with incentives and reasons to alter his criminal behaviour.”

But rather than forcing Gaddafi to back down, prosecutors later stated that the air strikes prompted him to take further action – to bomb Pan Am flight 103.

AFTERMATH OF THE CRASH

Americans who lost loved ones in the attack demanded answers and were relentless in their pursuit for the truth. Many families testified before US Congress and, in 1990, a presidential commission released a report blasting the US civil aviation security system for ‘failing to provide the proper level of protection for the travelling public.’

A British father of one of the victims went one step further.

He wanted to test the safety regulations by putting a fake radio cassette player bomb in a suitcase on a flight.

The fake bomb managed to travel undetected from London to New York, then onto a second aircraft from New York to Boston.

US Congress quickly passed a bill to set up new training standards for airport security staff and also a method of warning passengers about terrorist threats.

Pan Am shouldered much of the blame for the attack and was hit with several lawsuits for violating security rules. The airline company declared bankruptcy in 1991 and soon after, ceased operating.

A three-year investigation, involving experts from the US, Britain and Germany, questioned more than 15,000 people across 30 countries. They collected thousands of pieces of evidence that resulted in arrest warrants being issued, in 1991, for two Libyan nationals; Libyan intelligence agents, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamen Khalifa Fhimah.

Investigators believed al-Megrahi and Fhimah manufactured the bomb out of Semtex plastic explosives, hid the bomb in a cassette recorder which was placed inside a suitcase. The suitcase was then put on-board an Air Malta flight, travelling from Malta to Frankfurt, Germany. It’s believed the unaccompanied bag was transferred to a Pan Am flight to London before being placed on-board Flight 103.

At first Gaddafi refused to hand the two men over to authorities but, following negotiations and UN sanctions, he agreed to a deal in which the men would go on trial in the neutral Netherlands, under Scottish law. Three Scottish judges presided; there was no jury.

In 2001, al-Megrahi was jailed for life after being found guilty of 270 counts of murder.

Fhimah was found not guilty.

In 2003, Gaddafi accepted responsibility for the bombing – but he never admitted guilt – and paid compensation to the families of the victims (around $11 million AU per victim) But he always maintained that he never gave the order for the attack.

Questions still remained, and some US investigators believed Iran was involved in the attack, possibly as revenge for a July 1988 incident in which a US warship accidentally downed an Iran Air plane, killing 290 passengers.

After serving just seven years in prison, al-Megrahi was released by the Scottish government on compassionate grounds after he was diagnosed with cancer.

His release caused outrage in the US and UK. When he died three years later, in 2012 at the age of 60, he was the only person to be convicted of the terror attack.

These days much of the wreckage can be seen in a scrap yard at Tattershall, north of London.

The distinctive blue and white Pan Am logo is still visible among the pile of shattered metal. It’s an eerie reminder of the devastation, the sheer waste and loss of human life.

— LJ Charleston is a freelance journalist. Follow her on Twitter @LJCharleston