Stormont shut down: Northern Ireland’s Parliament crisis explained

IF YOU’RE feeling frustrated by the situation in the Australian Parliament, spare a thought for the people who live in this country.

AND we think the political situation in Australia is bad.

Citizenship scandals, by-elections and non-binding postal votes may give Australians the impression not a lot is being done at the moment in our Parliament.

Well spare a thought for our Northern Irish cousins who have been stuck in a political rut for months. The semi-autonomous province has been deadlocked by a dispute between nationalists and unionists.

Things got so bad and nothing was being done that Britain last week voted to impose a budget on Belfast in a move seen as a step towards taking direct rule of the province.

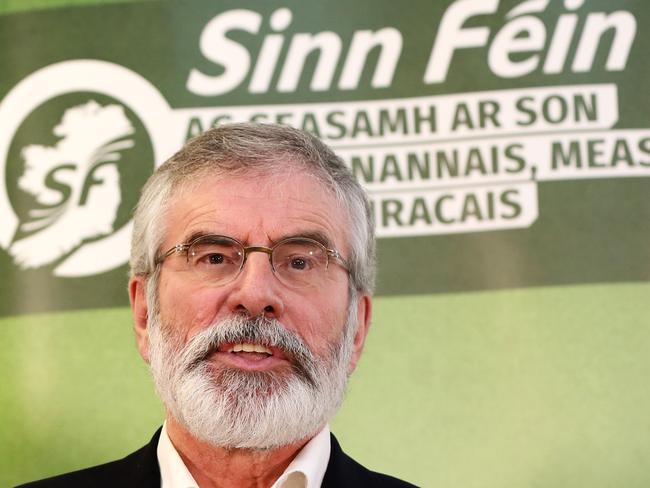

The saga continued; last weekend when Gerry Adams, the divisive politician known around the world as the face of the Irish republican movement, announced he was stepping down as leader of Sinn Fein next year after heading the party for over 30 years.

The Northern Ireland Assembly’s building, known as the Stormont, remains empty and all government decisions on spending remain on hold.

The deputy leader of the Alliance Party, Stephen Farry, said: “This is a more profound crisis than we’ve had at other times in the last 20 years.”

WHAT HAPPENED?

Northern Ireland has been without an executive for more than 10 months as its two largest parties hit a series of stalemates.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), currently in a coalition with its ruling Conservative Party, and the nationalists, Sinn Fein, have failed to agree on a power-sharing executive, wrangling over several issues including an Irish language law and same-sex marriage.

The power-sharing executive is the cornerstone of a peace process that ended three decades of violence in Northern Ireland between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists.

Talks between the two parties fell apart in January when the Irish republican party Sinn Fein pulled out after months of simmering conflict with the pro-British DUP.

DIVISIVE FIGURE STEPS DOWN

Mr Adams, who has been president of Northern Ireland’s second-largest party since 1983 — told the party’s annual conference in Dublin he would not run in the next Irish parliamentary elections.

“Leadership means knowing when it is time for change and that time is now,” the 69-year-old said, adding the move was part of an ongoing process of leadership transition within the party.

The death of Mr Adam’s former colleague, Martin McGuinness, in March has compounded the problem.

According to the New York Times, Mr Adams stepping down “deprives the government of established leaders who are willing or able to make compromises on both sides of the sectarian divide”.

But he remains a divisive figure — some have denounced Mr Adams as a terrorist while others hail him as a peacemaker.

He was a key figure in Ireland’s republican movement, which sought to take Northern Ireland out of the UK and unite it with the Republic of Ireland.

The dominant faction of the movement’s armed wing, the Provisional IRA, killed nearly 1800 people between 1970 and 1997 during a failed campaign to force Northern Ireland out of the UK.

It renounced violence and surrendered its weapons in 2005 although many identify Mr Adams as a member of the IRA since 1966 and a commander for decades, something he denies.

Mr Adams was key in the peace process that saw the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and the formation of the power-sharing government in Northern Ireland.

Many believe Sinn Fein’s popularity among voters is hampered by the presence of leaders from Ireland’s era of The Troubles.

CRISIS GROWS

Stephen Farry, the deputy leader of the centrist Alliance Party, told the New York Times the crisis was the worst it’s been in 20 years.

The assembly has been suspended before, between 2002 and 2007, but he said this seemed so much worse.

“But then there was the sense that this was a blip and the problems would be overcome,” he said. “This crisis has a different feel to it.”

WHAT NEXT?

Northern Ireland Secretary James Brokenshire said the budget imposed last week was with “the utmost reluctance” and said there was “no other choice” after the failure of months of efforts to bring the two sides in Belfast’s power-sharing assembly together.

“My strong preference would be for a restored executive in Northern Ireland to take forward its own budget,” he told MPs during a debate.

Mr Brokenshire had been warning for weeks that Westminster would be forced to step in, and such a budget was needed to keep public services running.

However, British opposition political parties voiced concerns.

“If this is not direct rule, this is getting perilously close to it,” Owen Smith, Labour’s shadow Northern Ireland secretary, told MPs.

“Direct rule would be a massive backwards step,” he said, adding the province was now entering a “twilight zone between devolution and home rule.”

Ireland’s Foreign Minister Simon Coveney said he was “deeply disappointed” months of negotiations had not yielded a deal.

He said he remained confident an agreement could be reached on the basis of the 1998 peace accord that first devolved government to the province.

— with AP and AFP