Hard Brexit is causing ‘genuine anxiety’ and threatens to disturb ‘fragile peace’ in Northern Ireland

AS THE Brexit deadline looms, tension is building over what will happen to the border separating Northern Ireland and the Republic.

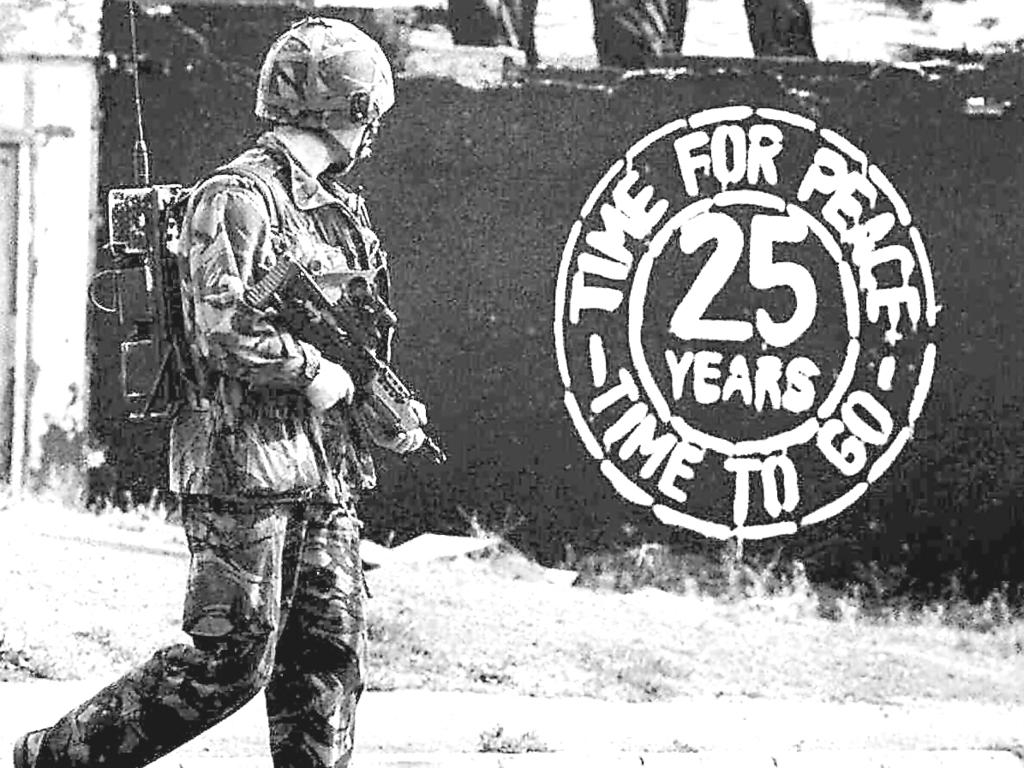

THE prospect of a hard Brexit is causing “genuine anxiety” for people in Northern Ireland — especially those whose memories of a patrolled border are still fresh.

While the 500km land border which divided Northern Ireland from the Republic of Ireland has not been in place for 20 years since after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement brokered a peace deal ending three decades of violence, the issue has reared its ugly head again.

Currently, people and goods are able to move freely, there are no checkpoints and euros and sterling are both accepted in local shops.

But once the UK withdraws from the European Union — leaving the single market economy and customs union — border checks would need to be reintroduced, given the Republic will remain inside the European Union and its northern neighbour will remain inside a new “sovereign” Britain.

There are fears the peace that currently exists could be under threat and a new wave of violence might erupt once Brexit happens, given that no one knows how the border will work and it appears likely checkpoints will be needed to monitor movement between the two jurisdictions which will operate under different regulatory systems.

Talks have now stalled over a disagreement on the so-called Northern Irish “backstop”, an insurance policy to ensure there will be no return to a hard Irish border if London and Brussels fail to reach a trading agreement in time.

As the date Britain is due to leave the European Union draws ever closer, tensions are rising across the country and almost 700,000 people descended on London at the weekend for the largest anti-Brexit protest since the 2016 referendum.

While British Prime Minister Theresa May has committed to ensuring the open border remained in place even if Brexit occurred without a trade deal, Ireland’s ambassador to the UK Adrian O’Neill said there appeared to be a degree of backsliding on the “Irish backstop”.

“We should be in no doubt that the prospect of Brexit, especially a hard Brexit, or a no-deal Brexit, is causing genuine anxiety in Northern Ireland,” Mr O’Neill said.

He went further to suggest that a no-deal border had the capacity to “disturb the delicate and complex balance of the Good Friday Agreement and disrupt the fragile peace”, The Guardian reported.

Several key questions remain. Will you need an identity check as you cross over? Will goods need to be checked? Given immigration was a major factor in the Brexit debate, will there eventually need to be some sort of physical border?

And inevitably, how will all this affect relations between Irish republicans and unionists?

This complicated quandary — described as a “Gordian knot” by EU President Donald Tusk — has led to intense talks between Britain and the EU grinding to a halt, leaving the UK on the brink of economic and political chaos as anger and frustration mounts across the country.

Former foreign secretary Boris Johnson, who supports a hard Brexit and has been highly critical of Ms May’s negotiations with Brussels, recently described the Irish backstop in Brexit negotiations as a “monstrosity” that wiped out the UK sovereignty.

In a column in the Telegraph last month, Mr Johnson wrote: “If the Brexit negotiations continue on this path they will end, I am afraid, in a spectacular political car crash.”

For those living on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, there is a real fear about what Brexit will mean if a trade deal is not reached with the EU and a physical border with patrolled checkpoints is installed.

Rory Reynolds, of South Armagh, just 5km north of the border, said he feared a hard border could reignite violence in the area — which was part of the Irish Republican Army’s heartland and nicknamed “bandit country” by the British.

“The Irish border issue appears to have become the biggest hurdle to making a deal between the EU and the UK, yet it was barely mentioned in England during the referendum debate,” Mr Reynolds told news.com.au.

“For us in Ireland it was an obvious and major problem.

“Hard Brexiters like (Conservative politician Jacob) Rees-Mogg and Boris Johnson seem to continue to dismiss this as an issue by pretending it is minor and can be overcome.”

Talks between London and Brussels are deadlocked over how to avoid a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic while the British Government’s National Audit Office has warned there would not be enough time to prepare its borders for a hard Brexit by March 29, 2019 — the date the UK is set to leave the EU.

It said Border Force would be unable to hire enough staff in time, critical IT systems would not be up and running while infrastructure to track goods and physically examine them at ports would not be in place by then.

“For us living on the border, there is no border,” Mr Reynolds said. “People travel back and forth on a daily basis. Farms are in both the north and in the south. Sterling and euros are accepted in shops. People live in one jurisdiction and work in the other.

“A hard border will put this at risk. The Good Friday Agreement enshrined north/south co-operation. A hard border will break this peace agreement and will inevitably involve a return of uniformed British customs and security personal.

“This could motivate a new generation of young men who could pick up the gun in the age-old ‘struggle’ against Britain.”

For years South Armagh and surrounding neighbourhoods were plagued by violence.

In total, it’s estimated 3600 people lost their lives and many more thousands were injured during the Northern Ireland conflict known as “The Troubles” — a period of escalating violence after 1969 which raged for three decades.

The conflict between nationalists (mostly Irish Catholic) and unionists (mostly Protestants who identified as being part of the UK) finally ceased when the Good Friday Agreement was reached on April 10, 1998.

It was ratified some weeks later, restoring self-government to Northern Ireland. Over the convening years, paramilitary groups began to decommission their weapons and British security forces were recalled from the Irish border.

However, once the UK withdraws from the EU, there are fears the peace that currently exists could be under threat.

“During The Troubles, 27,000 heavily armed soldiers failed to close the border, yet Boris (Johnson) seems to think a few CCTV cameras and electronic tags will be able to do just that,” Mr Reynolds told news.com.au.

“Hard Brexiters seem to have questionable motives for their obtuse stance. Were those who voted ‘leave’ fully informed of the consequences?”

Last weekend, almost 700,000 people from all over the UK travelled to London for the People’s March, the largest anti-Brexit demonstration since the 2016 referendum.

In the lead-up to Saturday’s march, a rousing video, published by anti-Brexit organisation Best For Britain, called on Brits to say, “I’m as angry as hell” and demand a People’s Vote on the final deal as confusion intensifies over what Brexit will actually mean for ordinary people.

“The only way to overturn the referendum is with another referendum,” Mr Reynolds said.

“In 2015 the public didn’t know what was at fully at stake. It is now much clearer what ‘leave’ actually means therefore calling for another referendum is legitimate but it could only be called once that arrangement or deal has been made with the EU.

“Democracy allows the right that you can change your mind.”

— with Ben Graham and wires

Continue the conversation with Rebecca Franks on Twitter @MrsBecFranks