Did a power nap cost Adolf Hitler victory in World War II? Staff were too scared to wake him on D-Day

THE world would be a very different — and much nastier — place if one simple thing had happened, 70 years ago today.

IT’S a day that determined the direction of history, signalling the downfall of Hitler’s Germany.

But the Nazi leader could have been victorious — and the world would likely be a different, and much nastier place — if one seemingly ludicrous thing had been different.

His aides were too scared to wake him up.

Despite the overwhelming might of the combined forces of Russia, Britain and the United States, the outcome of World War II was a close-run thing.

HIGH-STAKES GAMBLE

The invasion and liberation of Nazi-occupied western Europe we know as D-Day simply had to succeed.

For the Allies, failure was unacceptable. If their troops were rolled back into the ocean as they stormed the beaches of Normandy, Germany would be in an unassailable position.

While outright victory may have been a long shot for Hitler’s evil regime, it is probable a peace treaty carving up Europe between Germany and Russia — and its equally brutal despot Josef Stalin, who was attacking from the East — would have resulted.

As dawn broke on June 6, 1944, Germany was still in with a strong chance.

Its army was well entrenched. Its superb tanks were positioned in readiness for a rapid counter-strike on any allied bridgehead along the coast of Northern France. The vaunted Luftwaffe — struggling with dwindling supplies and fuel — had husbanded its aircraft and supplies in readiness for a “maximum effort” response at such a key time.

America’s famous battlefield commander General Eisenhower knew this. Despite his confident words to troops on the eve of his greatest adventure, he had quietly prepared an “in case of defeat” letter.

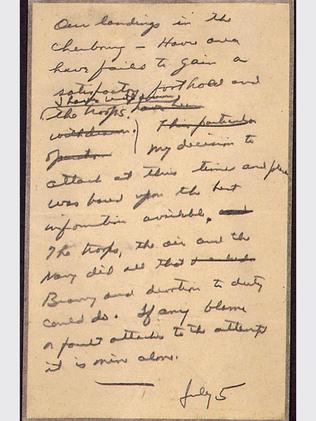

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

Victory or defeat, it all hinged on one thing.

Adolf Hitler.

THE SLEEPING GIANT

Germany’s charismatic supreme commander had vehemently reserved the ultimate say on when and where any of his most elite military forces were to be committed in response to invasion.

The problem was, he was a fractious man — known for temperamental outbursts and imposing instant demotions if displeased.

So, when the first urgent but confused reports of an Allied landing were radioed and rung through to the Wolf’s Lair headquarters as early as 4am on the morning of June 6, his staff found him asleep.

Nobody dared wake him.

Better to let the great man sleep, and give him the clearest possible picture when he wakes — right? Confusion was rife and actively enhanced by a key double-agent in the pocket of the Allies, plus an intelligence campaign severely misleading the Germans.

And, besides, the weather over Normandy had been forecast to be atrocious, leading many Germans to believe any action there was simply a feint — and that the main attack would come northwards at the area around Calais.

“We don’t know” was simply not an answer for the Fuhrer.

This simple hesitation by cowed staff may have cost Germany, if not victory, a tremendously advantageous negotiated peace.

It certainly gifted the Allies 12 vital hours.

Germany’s reserve tanks and troops — which could have responded within minutes — instead sat and waited. The 10,000 border troops hiding in their pillboxes and trenches were left to hold the line alone as 175,000 Allied troops steadily waded ashore.

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

General Erwin Rommel — the feared German “Desert Fox” tank commander who won the respect, and fear, of the Allies for his revolutionary tactics in North Africa — was at home in Germany celebrating his wife’s 50th birthday.

He urgently raced back to the front line, but found his hands tied.

Rommel repeatedly tried to contacted Hitler’s office and chiefs of staff. He was put on the 1940s equivalent of “hold”.

Only one man — a derided old general by the name of Field Marshal Rundstedt — dared take the initiative. He overstepped his authority and, at 7am, ordered two reserve tank divisions to quickly move to Caen, before Allied aircraft made the move impossible.

Then he contacted central command: No, he could not move the tanks. He had to wait for Hitler’s command.

When Hitler finally roused himself to take action — at 4pm in the afternoon — he approved the reinforcement of Caen.

But by the time belated orders to move the tank forces eventually came, Allied Typhoon, Mustang and Mosquito attack aircraft ruled the skies — blasting everything they saw off the battlefield. The British, US, Canadian and Free French troops had reorganised after their chaotic push up the beaches. Key Allied equipment, such as tanks, heavy guns and ammunition, were in place after their perilous passage over the English Channel.

Nothing Germany had could now be moved without risking destruction.

It had been 12 blissful hours of ignorance on the Fuhrer’s behalf.

General Eisenhower’s anticipated apology letter was never posted.

The rest, as they say, is history.

DROP INTO D-DAY FREZONE: Invasion reenactments go off with a bang, video.