How India’s COVID outbreak got so bad, as World Health Organisation warns it could happen to other countries

Earlier this month India was celebrating its success against COVID, now it is burning bodies in car parks. So how did it get to this point?

As recently as two weeks ago, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi delighted in addressing a cheering crowd at an election rally.

“I’ve never seen such huge crowds,” Mr Modi said in West Bengal on April 17 – even as India set a world record of 230,000 new coronavirus cases in 24 hours.

On the other side of the country, an estimated 25 million Hindu pilgrims had gathered across several weeks for the Kumbh Mela festival in Haridwar, to bathe in the Ganges river mostly without masks or social distancing.

Driven by a sense of “triumphalism”, Mr Modi even told the World Economic Forum in January that India had “defeated” the virus — but now it appears to have slowly marched towards a humanitarian crisis of “astonishing” proportions.

At the time, India had a relatively low number of cases, just 11,000 per day in a country of 1.4 billion.

But this month India recorded almost six million new infections, dashing hopes at the start of the year that it may have seen the worst of the pandemic.

The belief that India had avoided catastrophe led the government to lower its guard allowing most activity to return almost to normal, including weddings and permitting spectators at cricket matches.

“The government has been caught with its pants down,” call centre executive Navneet Singh, 38, told AFP.

On Wednesday, India set another world record for the number of cases recorded in a single day, reaching 360,960 confirmed cases as well as 3293 deaths. In total, more than 195,000 people have died from the coronavirus.

In New Delhi, AFP images showed smoke billowing from dozens of pyres lit in a car park that had been turned into a makeshift crematorium.

“People are just dying, dying and dying,” said Jitender Singh Shunty, who is co-ordinating more than 100 cremations per a day at the site in the east of the city.

RELATED: Flights between India and Australia suspended

“If we get more bodies then we will cremate on the road. There is no more space here,” he said, adding: “We had never thought that we would see such horrible scenes.”

India’s healthcare system has long been underfunded and the new COVID-19 outbreak has caused critical shortages in oxygen, drugs and hospital beds, sparking desperate pleas for help.

Patients’ families have taken to social media to beg for oxygen supplies and locations of available hospital beds.

As the crisis worsens, India’s Hindu-nationalist government faces growing criticism for allowing mass gatherings across the country in recent weeks.

The glitzy Indian Premier League is also under pressure, with a leading newspaper suspending coverage and slamming the IPL’s decision to keep playing cricket as “commercialism gone crass”.

“I have just one word (for the current situation), which is appalling,” college student Ananya Bhatt, 22, told AFP.

“This is all a result of the gross mismanagement by the government … What kind of a country leaves its citizens to suffocate and die in this manner?”

“People are dying because hospitals can’t give them oxygen. Who is responsible for their deaths? It is the government, it has failed us,” vegetable vendor Mukhtar Ali, 43 said.

So how did this happen?

‘Everyone wanted to get back to work’

Early in the pandemic, politicians were careful to set a good example by following restrictions, but they slowly began to relax and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who imposed a nationwide lockdown last year, began to be seen as an anti-lockdown champion.

In February, the national committee of India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), passed a resolution arguing that India had been successful in fighting COVID-19.

Health Minister Harsh Vardhan said in March that India was “in the endgame” of the pandemic and praised Mr Modi as a “vaccine guru” and “example to the world”, The Sunday Times reported.

Workplaces, markets and shopping malls were reopened. Couples quickly made up for lost time during the pandemic, holding large weddings, many of which had been postponed.

Large mostly maskless crowds also attended two cricket Tests between India and England last month, which were held in Mr Modi’s home state of Gujarat, in the Narendra Modi Stadium.

Four large states also moved forward with elections and thousands of voters turned up for rallies, with Mr Modi initially expected to address more than 20 events. Other ministers were expected to appear at more than 50 events each.

Cases were already on the uptick in February and reports of new variants were emerging but the government’s COVID-19 task force reportedly did not even meet in February or March.

RELATED: India’s rich flee country on private jets

One of the problems, according to Foreign Policy, was India’s relatively small $US265 billion ($A342 billion) coronavirus aid package which meant its population needed to get back to work quickly as longer lockdowns were unsustainable.

“I said in February that COVID had not gone anywhere and a tsunami would hit us if urgent actions were not taken,” Abdul Fathahudeen, a critical care expert on Kerala state’s COVID task force told The Times.

“A false sense of normalcy crept in and everybody, including people and officials, did not take measures to stop the second wave. Sadly, a tsunami has indeed hit us now.”

Public Health Foundation of India president K. Srinath Reddy told the BBC: “There was a feeling of triumphalism. Some felt we had achieved herd immunity. Everyone wanted to get back to work. This narrative fell on many receptive ears, and the few voices of caution were not heeded.”

Only recently has Mr Modi suspended BJP campaigning in state elections.

Seeking for Salvation

With political rallies being hosted across the country, it was hard to argue religious events couldn’t also be hosted.

Even though a Muslim religious gathering held last year had become a superspreader event, the huge Kumbh Mela festival was allowed to go ahead.

The festival is a Hindu pilgrimage normally held every 12 years in the ancient city of Haridwar, along the Ganges River.

The festival can last between one and three months depending on astrological conditions, with numbers expected to peak this year on the most auspicious days of April 12, 14 and 21, when five million people per day were expected, professor of anthropology, religion and transnational studies Tulasi Srinivas of Emerson College explained in a piece for The Conversation.

The festival is the largest religious gathering of its kind in the world and in total about 100 million celebrants were expected to participate this year.

“Hindus believe that bathing in the sacred Ganges on the auspicious days of the festival leads to salvation from the endless cycle of reincarnation,” Prof Srinivas wrote.

Several measures were announced to control the spread of the disease including thermal screening checkpoints, limited bathing times and recent negative COVID-19 test results for participants.

But some participants have since revealed the lack of strict controls at the festival.

RELATED: Aussie cricket players stranded in India

Ujwal Puri, a 34-year-old businessman, told the BBC he arrived in Haridwar on March 9, ahead of the first day of bathing on March 11.

He said he faced no checks at the airport or in Haridwar and many people were not wearing masks.

“There was no social distancing,” Mr Puri said. “People were sitting cheek-by-jowl for the holy prayers in the evening.”

By April, local authorities were recording huge jumps in positive tests.

Haridwar’s chief medical officer, Dr SK Jha, said more than 1600 cases had been confirmed among participants in just four days between April 10 and 14, the BBC reported.

India’s total coronavirus cases, which were hovering around 12 million on April 1, with 162,900 deaths, according to John Hopkins University, had jumped to more than 14 million and 174,000 deaths by mid-April.

This has now risen to more than 17 million cases and 197,894 deaths.

Mr Modi has finally urged Hindu devotees to stay away from the Ganges and to celebrate symbolically, although it’s believed people who attended the festival are already driving up case counts in some states.

New ‘double mutant’ variant

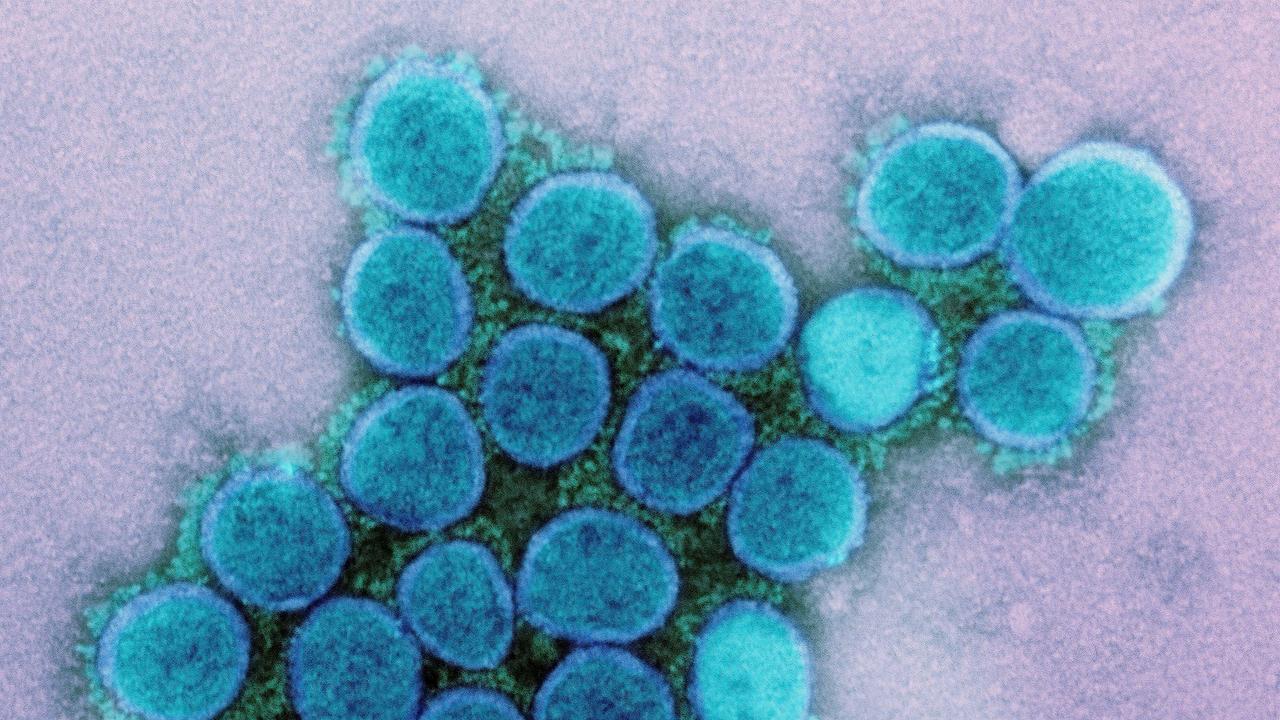

The second wave in India has also been blamed on a new “double mutant” virus variant named B. 1.617.

The World Health Organisation recently listed B. 1.617 as a “variant of interest” but has stopped short of declaring it a “variant of concern”. That label would indicate that it is more dangerous than the original version of the virus by – for instance – being more transmissible, deadly or able to dodge vaccine protections.

Preliminary modelling indicates “that B. 1.617 has a higher growth rate than other circulating variants in India, suggesting potential increased transmissibility”.

The WHO also noted other more easily spread variants may be combining with B. 1.617 and “playing a role in the current resurgence in this country”.

“Indeed, studies have highlighted that the spread of the second wave has been much faster than the first,” the WHO said.

It highlighted though that “other drivers” could be contributing to the surge, including lax adherence to public health measures as well as mass gatherings.

“Further investigation is needed to understand the relative contribution of these factors,” it said.

The UN agency also stressed that “further robust studies” into the characteristics of B. 1.617 and other variants – including impacts on transmissibility, severity and the risk of reinfection – were “urgently needed”.

A number of variants are circulating in India, including the more virulent B117 strain that originated in the UK.

“There’s some evidence of multiple overlapping epidemics happening in India, rather than one monolithic outbreak,” Jeffrey Barrett, director of the COVID-19 Genomics Initiative at the Welcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge told the Financial Times.

“Which makes sense since it’s a huge, heterogeneous country.”

Scientists have also pointed out there is not enough evidence yet on whether the variant is to blame for the outbreak, partly because little genome sequencing has been completed in India.

“There has been a lot of focus on the B. 1.617 variant,” Michael Head, senior research fellow in global health at Southampton University in the UK told the Financial Times. “But it’s the mixing of susceptible populations that ultimately drives the transmission of respiratory infectious diseases.”

Faltering vaccine rollout

India is also home to the world’s largest vaccine producer, the Serum Institute of India, but has not made much headway into vaccinating its 1.4 billion population.

About 140 million jabs have been delivered in India, with about 1.6 per cent of recipients receiving both doses. From May 1, all adults will be eligible for the jab.

In February, the government ordered the institute, which makes the AstraZeneca vaccine for the United Kingdom, European Union and the Covax program, to halt exports so it could focus on manufacturing vaccines for India.

But the institute said it could not increase supplies because of a lack of funding and US restrictions on raw materials.

On Monday, US President Joe Biden announced the country would send up to 60 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine overseas, with India appearing to be a leading contender to receive at least some supply.

“India was there for us, and we will be there for them,” Mr Biden tweeted, referencing India’s support for the United States when it was enduring the worst of its COVID crisis.

‘This can happen in a number of countries’

Many parts of India have now tightened restrictions, with the capital New Delhi extending its week-long lockdown and all non-essential services banned in Maharashtra.

The northern state of Uttar Pradesh, home to 240 million people, goes into a shutdown this weekend, as will Karnataka, home to IT hub Bangalore.

The Indian Premier League cricket tournament is still being played behind closed doors in six Indian cities.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus voiced alarm on Monday at India’s record-breaking wave of COVID-19 cases and deaths, saying the organisation was rushing to help address the crisis.

“The situation in India is beyond heartbreaking,” Mr Tedros told reporters.

He said the UN health agency was, among other things, sending “thousands of oxygen concentrators, prefabricated mobile field hospitals and laboratory supplies”.

The US, France, Germany, Canada and the EU have also promised to rush supplies to India.

Mr Tedros on Monday lamented that global new case numbers have been rising for the past nine weeks straight.

“To put it in perspective,” he said, “there were almost as many cases globally last week as in the first five months of the pandemic.”

The United States remains the worst-affected country, with some 572,200 deaths and over 32 million infections, followed by Brazil and Mexico.

But India, in fourth place, has in recent days been driving the global caseload.

“The exponential growth that we’ve seen in case numbers is really, truly astonishing,” Maria Van Kerkhove, the WHO’s technical lead on COVID-19, told reporters.

She warned that India was not unique, pointing out that a number of countries had seen “similar trajectories of increases in transmission”.

“This can happen in a number of countries … if we let our guard down,” she said.

“We’re in a fragile situation.”

– With AFP