How Australia beat COVID-19 while the United States and Britain broke

Australia has been hailed across the world as a COVID-19 success story while the UK is still crippled by its grip. It’s because of a “serious mistake”.

Australia is a fortress of hope in a world conquered by COVID-19. But, even as vaccines raise the prospect of relief, the siege is growing stronger. And the cracks in our defences are growing.

Incompetence. Hesitance. Partisan politics.

All are being blamed across the world for overwhelmed health systems, stalled economies and soaring death rates.

Australia has dodged these bullets. So far.

A federal government accused of repeatedly ignoring expert advice before the devastating 2019 bushfires was suddenly eager to put epidemiologists at the heart of the public health emergency.

Go fast. Go hard. That’s the advice Australia – and its states – received and acted upon.

RELATED: ‘Dominant strain’: New crisis coming

Meanwhile, the United States prevaricated. Great Britain hesitated.

Profit versus pandemic equations were being crunched around the world.

Now they’re paying the price.

Some 451,000 people have so far died in the US, and its economy contracted 3.5 per cent. The toll is about 108,000 in the UK. The economic contraction is about 9.7 per cent.

In Australia, 909 lives have been taken by this poorly understood disease.

And its economy, while wounded, remains in fighting form. Can it stay that way?

A DEFEATED WORLD

“Everything broke,” WHO health emergencies head Michael Ryan told the World Health Organisation’s Executive Board’s annual meeting last week.

International agreements. International law. International co-operation.

All went by the wayside in the face of COVID-19.

The board heard that – despite years of warnings – preparations for global pandemic were not adequate. That alert and response systems were outmoded. That warning signs were ignored.

This is why it took the WHO four weeks after the virus was identified to declare a “public health emergency of international concern”.

RELATED: Where contagious virus strain originated

But the blame doesn’t only rest with the WHO.

“(Even then), too many countries failed to act quickly and decisively enough to apply necessary and recommended public health measures,” says pandemic preparedness head Helen Clark.

Even the testing needed to identify the pandemic’s spread failed, Mr Ryan says.

“It was not just a supply issue,” he explained. “There were manufacturing issues. There were raw material issues. There were distribution issues. There were error issues. There were competitive issues between member states.”

And there were societal issues – such as conspiracy theories and disinformation from trusted sources.

“A closer look at the international response to COVID-19 reveals two new developments that have exacerbated the impact of and response to the pandemic – politicisation and securitisation,” US Council on Foreign Relations global health senior fellow Yanzhong Huang wrote in Foreign Affairs.

“It did not have to be this bad. The inconsistency and incompetence of President Donald Trump’s administration compounded the toll of the pandemic, but so did larger forces partly beyond any one government’s control, from politics to protectionism to paranoia.”

HE WHO HESITATES …

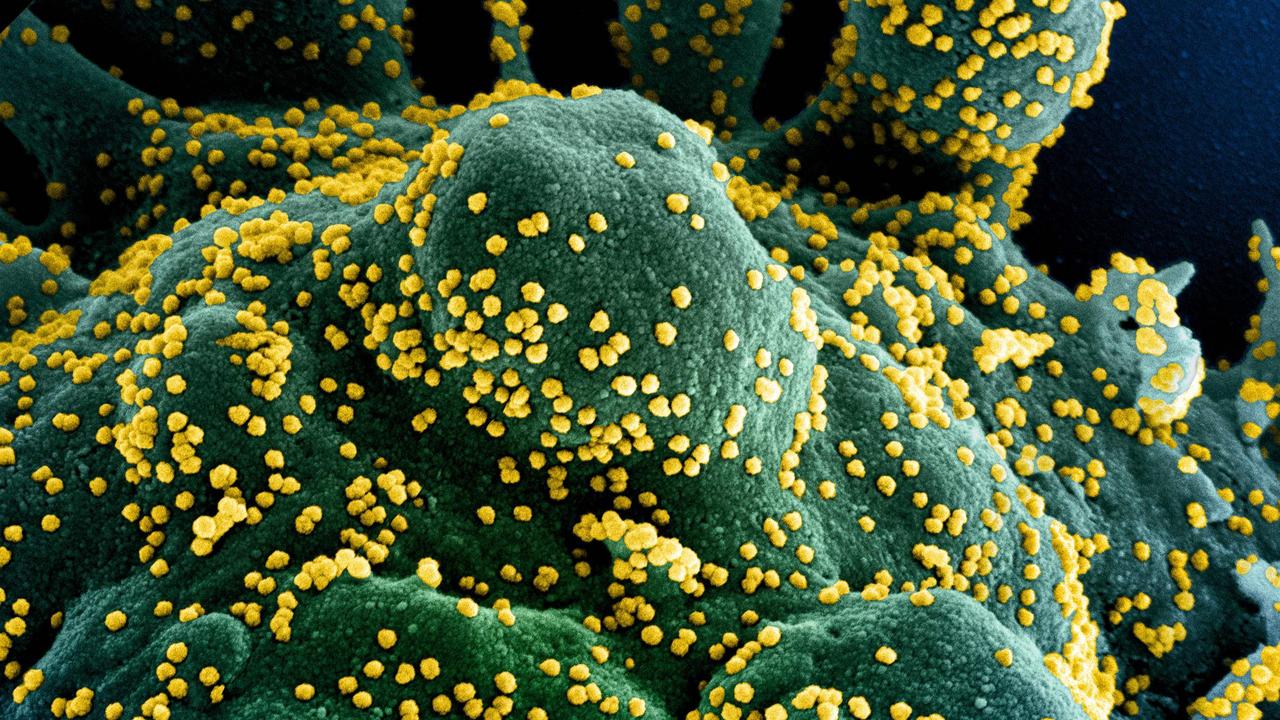

This time last year, the world knew very little about the strange new mutation of the coronavirus coming out of Wuhan, China. But we knew it was extremely contagious. And that its fatality rate seemed far greater than the flu.

In the face of such uncertainty, the only immediately available weapon was the blunt instrument of isolation. To stop transmission. To starve it of new hosts in which to incubate.

RELATED: Australia secures extra vaccines

But the costs would be enormous.

Businesses and industries were shut down. Social interactions ended.

The price of total lockdown was vanishing profits.

The need for total lockdown was potentially pandemic overkill.

Whether or not it was necessary remains open to debate.

Whether or not it worked is not.

“In the early days of the epidemic, as the novel coronavirus began jumping borders, countries rushed to institute travel barriers and install protectionist measures,” Mr Huang wrote. “Instead of working together to contain the outbreak, major powers quarrelled over who should be deemed responsible.”

But competition was compounded by hesitation, error and poor judgment.

“To be fair, the world health body did make a series of missteps. It delayed declaring the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), demonstrated an inability to enforce international health regulations in a coherent and effective manner, and deferred too much to China in an effort to seek its co-operation in disease surveillance and response,” Mr Huang writes.

The virus – always seeking a weakness – quickly found its way through the few barriers placed in its path.

COMPLACENCY KILLS

Parts of Australia have been COVID-19 free for weeks and months. More and more restrictions are being lifted. More and more community and economic activity is being restarted.

COVID-normal is here.

And that makes the nation vulnerable to an outbreak.

Which is why “go hard, go fast” remains the tactic of choice once the pandemic jumps containment lines.

“The trick for us will be keeping our community transmission free,” says Deakin University epidemiologist Professor Catherine Bennett. “If we can do that over our summer, then we’ll actually be in a better position than the northern hemisphere.”

With no community transmission, the virus-friendly winter environment will have nothing to accelerate. No flare-ups will be generated.

“What we’re aiming for is to keep the virus at the gate,” she says. “It’ll be onshore. It’ll be in our hotel quarantine. If we can keep it there, then we won’t be at risk coming into autumn.”

Much depends on whether or not these quarantine measures hold up over the next few weeks.

A breakout could happen, again, at any time.

“But we’re preparing for that,” Prof. Bennett says. “Because, again, we don’t quite know what’s going to happen”.

What remains unclear, however, is the most appropriate response.

“I think we have to learn from the experiences right across the world to understand what’s too much, and what’s the right amount, and what’s too little,” she says. “And I think that’s the learning which will benefit from the fact that we’ve done it differently around the world. And we can then say, ‘OK, you know, this is what we need to do.’”

COMBAT FATIGUE

Australia’s community and political commentators are showing signs of combat fatigue.

“So we are an island, as you say, and we can manage our borders,” says Professor Bennett. “But it’s proving a challenge because you’ve just got this constant pressure all the time of increasingly higher proportions of travellers coming back to Australia positive because rates have gone up overseas.”

This has resulted in our pandemic response becoming even more cautious, she says.

“I think it’s going to take years to really fully understand what we did. What worked well, what we did hang on to which bits you might do differently.”

The first wave, she said, was crushed by community engagement and timely government action. The second wave took harsher measures, such as steep fines and troops at roadblocks.

“There was this real panic,” says Prof. Bennett, “and there was starting to be a mood shift in politics, in the commentary, in the public. And some people were saying, ‘This is overkill. What are we doing? You know, we managed this the first wave, why are we now talking about much more strict restrictions?’”

The need, she says, was real.

“We really had shut down transmission, but we were also rebuilding our health system at the same time. So the challenge was actually having assurances that, you know, the health department’s response was now up to it,” she said.

“I hope it wasn’t necessary. And I hope when we go back and look at all of this, we’ll think, OK, we might not do it that way, next time.”

But such doubt also feeds conspiracy theorists and contrarians.

LEARNING CURVE

“You go to these very strict blanket lockdowns when you really don’t know what’s going on,” Prof. Bennett says. “You don’t know where it is. So you go blanket. What frustrated me was we went more blanket as time went on, not less.”

Testing capabilities have increased.

Contact tracing has been tested and refined.

Community education and information programs have improved.

What is needed most, Prof. Bennett says, is a sense of partnership between government, industry and the community.

“These viruses do discriminate, and they will find our weak points,” she says. “And we have to be open to that. And we have to be open to reviewing what we’ve done now to get better at this as we go ahead.”

What is the secret to Australia’s success?

We’re not yet sure.

“I think the key message here is that people’s behaviour and human contact is the main driver of spread,” British epidemiologist Dr Tom Wingfield told The Conversation. “But I also think that closing borders alone, once you have reached a certain threshold, and there is community transmission, is only obviously part of the response.”

The United Kingdom’s relatively slow implementation of lockdowns and travel restrictions allowed COVID-19 to gain a deep foothold in the community, he says. Other responses, such as contact tracing and rapid testing, also failed under pressure.

As a result, Britain has been in the grip of the pandemic far longer – and deeper – than Australia.

“So yeah, I think that the timing is critical,” Dr Wingfield says. “And I know that here, for example, the Home Affairs Committee in the UK has looked at that, and they have said themselves that they felt it was a serious mistake, that there wasn’t early closure of the borders.”

THE LONG GAME

COVID-19 is mutating. Its evolution is panning out faster than virologists had hoped.

Several new strains have emerged that are more contagious than the original. The original, as a result, has all but disappeared.

Soon, new strains able to ignore vaccines are expected to appear.

And that will prolong the pandemic – perhaps for decades.

Everything hinges on the speed and spread of the vaccine rollout.

If enough people worldwide are immunised, there won’t be a big enough pool of illness to generate fast-adapting mutations.

If not, we can expect more deaths and deepening economic crises. And yet another race to find an effective vaccine.

This is what makes COVID-19 a global crisis. Not just an Australian one.

“Millions of lives are at stake,” Mr Huang writes. “There is much to be gained from co-operation and much to be lost from conflict in containing a virus that knows neither political divides nor territorial borders.”

Meanwhile, Dr Wingfield says, the fates of Britain and Australia are in the hands of its politicians and media.

“I think we need to try and counteract and mitigate fake news and misinformation,” he says. “I think we can be helped by reliable media reporting there. I think the experts need to talk about what they’re experts in and not stray beyond. I think we need to be unafraid to admit when we don’t know and recognise that the things we say one day might need to change the next day. And I think the messaging from government needs to be a lot clearer than it has been.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel