GP explains why you’ve got a lingering cough after Covid

Coughing can be a common symptom of Covid, but what do you do when it lingers well after the virus is gone?

Since the start of the Covid pandemic, coughing has become an awkward symptom when out in public.

The problem is, though, it’s a symptom that lingers, with the Covid cough sometimes persisting for weeks or months after the infection has gone. In fact, around 2.5 per cent of people are still coughing a year after being infected with Covid.

A recurrent cough can undermine your capacity to work, leave you with medical bills, and lead you to withdraw from social situations because you don’t want others to fear you’re spreading Covid, The Conversation reports.

As a GP, I have patients ask whether there’s anything that can fix their post-Covid cough. Here’s how I answer.

What causes a Covid cough?

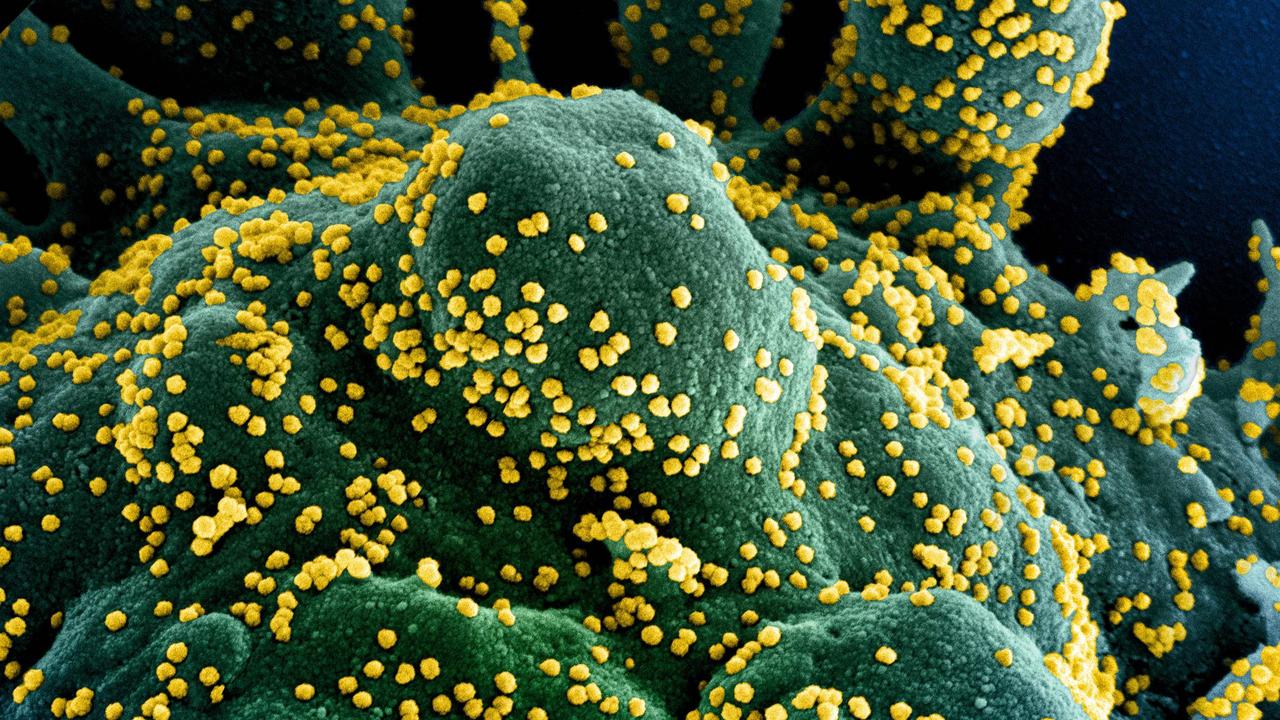

It’s not surprising Covid causes a cough, because the virus affects our respiratory tract, from our nasal passages right down to our lungs.

Coughing is one of the body’s ways of getting rid of unwanted irritants such as viruses, dust and mucus. When something “foreign” is detected in the respiratory tract, a reflex is triggered to cause a cough, which should clear the irritant away.

While this is an effective protective mechanism, it’s also the way the Covid virus spreads. This is one reason the virus has so effectively and quickly travelled around the world.

Why do coughs drag on after the infectious period?

Inflammation is a defensive process our immune system uses to fight off Covid. Inflamed tissues both swell up and produce fluid. This can last a long time, even after the virus has gone.

Coughing may persist for any of four key reasons, all of which involve inflammation:

• if the upper airways (nasal passages and sinuses) stay inflamed, the fluid produced drips down the back of your throat causing a “post-nasal drip”. This makes you feel the need to “clear your throat”, swallow and/or cough

• if the lungs and lower airways are affected, coughing is the body’s way of trying to clear the fluid and swelling it senses there. Sometimes there isn’t a lot of fluid (so the cough is “dry”), but the swelling of the lung tissue still triggers a cough

• the neural pathways may be where inflammation is lurking. This means the nervous system is involved, either centrally (the brain) and/or peripherally (nerves), and the cough isn’t primarily from the respiratory tissues themselves

• a less common but more serious cause may be the lung tissue being scarred from the inflammation, a condition called “interstitial lung disease”. This needs to be diagnosed and managed by respiratory specialists.

Interestingly, people may experience a range of post-Covid symptoms, including coughing, regardless of whether they were sick enough to be hospitalised. Some patients tell me they weren’t particularly unwell during their Covid infection, but the post-infective cough is driving them crazy.

When should you get it checked out?

We need to be wary not to label a cough as a post-Covid cough and miss other serious causes of chronic coughs.

One thing to watch out for is a secondary bacterial infection, on top of Covid. Signs you may have a secondary infection include:

• a change in the type of cough (sounds different, more frequent)

• change in the sputum/phlegm (increased volume, blood present)

• developing new symptoms such as fevers, chest pain, racing heart or worsening breathlessness.

Other potentially serious illnesses can cause a chronic cough, including heart failure and lung cancer, so if you’re in any doubt about the cause of your cough, have a check-up.

What can help the cough?

If the cough is mainly from post-nasal drip, it will respond to measures to reduce this, such as sucking lozenges, saline rinses, nasal sprays and sleeping in an upright posture.

Some people may develop cough hypersensitivity, where the threshold of the cough reflex has been lowered, so it takes a lot less to set off a cough. It’s a common response to colds and it can take a while for our bodies to “reset” to a less sensitive state.

If a dry or tickly throat sets off your cough reflex, solutions include sipping water slowly, eating or drinking honey, and breathing slowly through your nose.

By slow-breathing through your nose, the air hitting the back of your throat is warmed up and moisturised by first passing through the nasal cavities. Your cough reflex is therefore less likely to be triggered, and over time the hypersensitivity should settle.

If the cause originates from inflammation in the lungs, controlled breathing exercises and inhaled steam (in a hot shower or via a vaporiser) may help.

Thick mucus can also be made more watery by inhaling saline through a device called a nebuliser, which turns liquid into vapour and delivers it directly to the mucus built up in your lungs. This makes it easier to clear out with a cough.

Are there other options?

Budesonide (a steroid inhaler), when given early after a Covid diagnosis, has been shown to reduce the likelihood of needing urgent medical care, as well as improving recovery time.

Unfortunately, there are no good trials on using budesonide inhalers for a post-Covid cough.

However, anecdotally, it has been of help to some patients who have a post-Covid cough, when nothing else is helping them.

Trials on steroid tablets to treat a post-Covid cough are still under way, and won’t be recommended unless they’re shown to result in significant improvement.

Antibiotics won’t help

Concerningly, some countries have guidelines that suggest using antibiotics to treat Covid, showing just how prevalent this misunderstanding is.

Unless there is a secondary bacterial infection, antibiotics are not appropriate and may contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance.

Post-Covid coughing can last for weeks, be debilitating, and have a variety of causes. Most of the ways to manage it are simple, cheap and can be done without needing medical intervention.

However, if you have any doubts about the cause or the progression of your cough, it is worth a visit to your GP to have it checked out.

This story was originally published by The Conversation and has been reproduced with permission