Experts clear up common misconception about Covid vaccines

When you hear from the vaccine-hesitant, one argument comes up time and time again, but there’s a simple reason they’re wrong.

Despite getting off to a slow start, there is now a massive proportion of the Australian population vaccinated against Covid-19.

The latest figures from the federal government shows that more than 84 per cent of us aged over 16 have now had both doses, and the results are showing in the statistics on hospitalisations and deaths in our hardest hit states.

Although there are concerns about waning immunity over time and rare breakthrough cases of double-jabbed Australians falling gravely ill to the virus, the effectiveness of the jabs in reducing the number of us ending up in hospital is clear to see.

Australians who are vaccine-hesitant would really have to have their heads in the sand not to concede that point when looking at the number of deaths in nations around the world in this current wave of cases compared to the horrors of last year.

However, they are likely to bring up one argument up time and time again, and it seems like a fair point at first.

The argument is that the vaccines haven’t been proved to reduce transmission of the virus, so if somebody believes their immune system is strong enough and they don’t need a jab then they shouldn’t fell pressured to.

After all, they are ones taking the risk. If the jab is not effective in reducing transmission, and therefore the risk to others, then what’s the big deal?

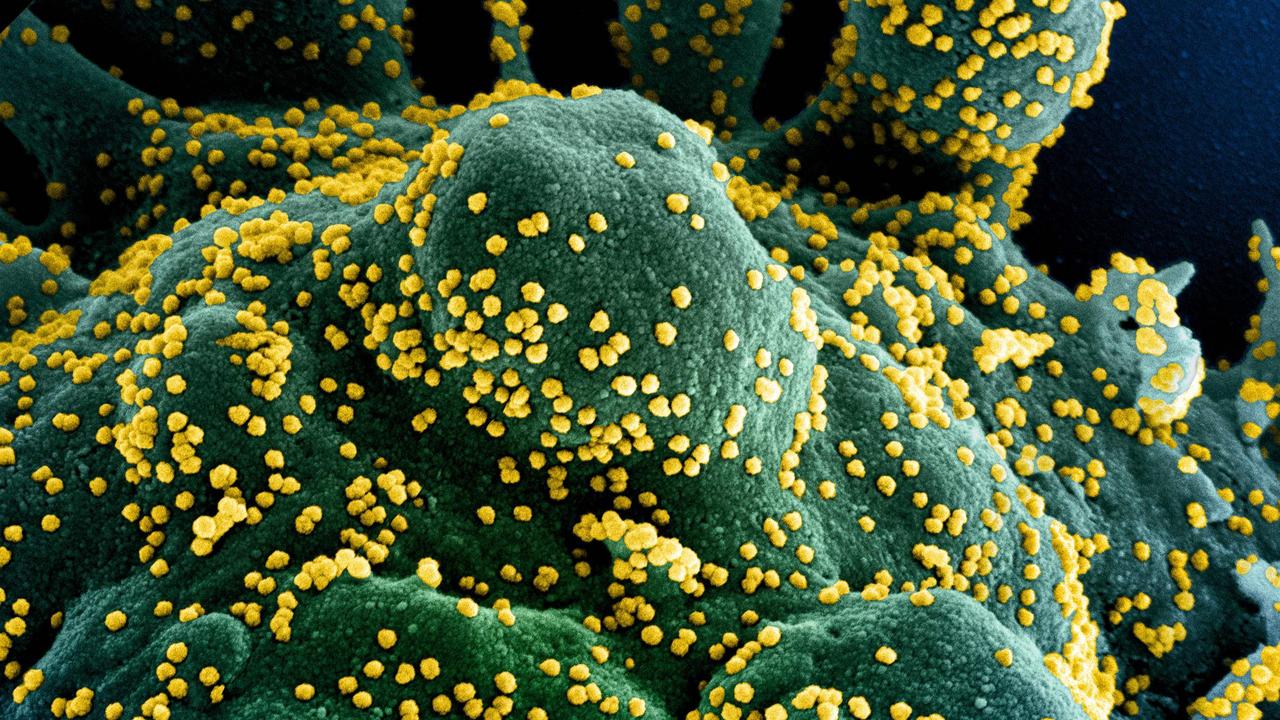

On social media they will often cite a handful of studies to prove their point. These recent studies have shown a similar peak in viral loads in vaccinated people compared to unvaccinated people who contract Covid, which to the untrained eye looks like our vaccine-hesitant friends have a point.

However, two medical experts have now pointed to a major flaw in their reasoning.

Dr. Jack Feehan, who specialises in immunology and regenerative medicine, and Vasso Apostolopoulos, a Professor of Immunology at Victoria University, have broken down what these studies actually mean.

In a piece for The Conversation today they wrote that studies only show a similar peak viral load, which is the highest amount of virus in the system over the course of the study.

However, what they don’t show is that vaccinated people clear the virus faster, with lower levels of virus overall, and have less time with very high levels of virus present.

Therefore, vaccinated people are, on average, likely to be less contagious.

Dr Feehan and Prof Apostolopoulos pointed to a study in the medical journal The Lancet that followed 602 primary close contacts of 471 people with Covid.

It found there were no differences in peak viral loads between vaccinated and unvaccinated people and only a small decrease in the number of infections in household members between vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

At first glance that would appear to suggest a similar level of infectiousness between both groups and, as Dr Feehan and Prof Apostolopoulos point out, a couple of other studies have shown similar results.

However, they argue that a crucial piece of information is missing — the information about overall viral load over time.

“While the peak load may be similar, vaccinated people are likely to have lower viral load overall, and therefore be less contagious,” they argued. “Given vaccines speed the clearance of Covid from the body, vaccinated people have less opportunity to spread the virus overall.”

They warned that even if you’re vaccinated and don’t feel sick you can still spread the virus to a vulnerable person around you, but the chance is much lower if you are vaccinated and if that vulnerable person is also vaccinated, the risk drops again.

“A vaccinated person is less likely to get Covid in the first instance, is less contagious, and is contagious for a shorter time, resulting in significantly less spread of the virus through a highly vaccinated community,” they wrote.

“This, combined with the well-known ability of vaccines to keep people out of hospital and ICU, makes them the most important part of the health response in the near future.”