Australian WHO virus expert reveals impact of coronavirus pandemic in Wuhan

An Australian virus expert visited coronavirus ground zero in the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the pandemic first began. Here’s what he found.

It has been more than 12 months since a mysterious, deadly new virus first began striking down the citizens of Wuhan before spreading across every corner of the globe.

And while China has managed to pull off the impressive feat of effectively controlling the coronavirus pandemic in the months since, for the people of Wuhan – COVID-19’s terrifying ground zero – life has still not returned to normal.

For a formerly bustling city of more than 11 million, the streets remain relatively empty.

Those who do venture out are masked at all times, follow stringent social distancing and hygiene practices and are under constant government surveillance.

And for so many, the trauma of staring down a lethal, unknown illness which claimed thousands of local lives clearly lingers.

RELATED: Follow all our live coronavirus Australia updates here

That’s the impression felt by Professor Dominic Dwyer, an Australian microbiologist and infectious diseases expert with NSW Health who recently spent four weeks in the city which became the epicentre of the pandemic.

Prof Dwyer travelled to Wuhan as part of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) 14-strong virus investigation team sent to study the outbreak’s origin.

He told news.com.au people there were still reeling from the tragedy, despite there being no recorded cases of COVID-19 community transmission since May 2020 in the city.

“I had the opportunity to talk to patients and doctors on the frontline, which was really valuable – it’s very easy to sit back and looks at the numbers … but talking to people affected one way or another really brings home the fact that at the end of every number, there’s actually a person who was either sick or died or lost a loved one,” he said.

“I spoke to a doctor there whose wife was also a doctor, and she died in intensive care after he had been unable to see her for the last two weeks of her life.

“She left behind a two-year-old child and that brought home that it’s not just a numbers game or a political game, it’s very personal for a lot of people.

“I talked to patients and doctors in the hospitals that had the first cases and to hear about the impact it had and to see the interpreters in tears and the Chinese investigators in tears, it was clearly very traumatic for them.”

Prof Dwyer and the team spent the first fortnight in hotel quarantine, before being able to meet with certain individuals and visit specific areas in the second fortnight, while under a “light” quarantine due to current public health rules.

RELATED: COVID-19 Vaccine side effects you could have

But it was enough to get a sense of a city that’s still grappling with the magnitude of the disaster, which killed more than 4600 of its own citizens and almost 2.4 million worldwide.

“It’s really very striking that Wuhan went through a terribly difficult period of time – yes, you could argue that things should and could have been done better, but at the end of the day they were dealing with something they knew very little about which had a very dramatic impact including in hospitals, where healthcare workers were also getting sick,” he said.

“They were in lockdown for 76 days without being able to go out of their apartments, and it was very, very tough on a personal level.

“Everybody wears masks everywhere, and there are not terribly many people wandering around. I imagine the economic impact would also have been significant.”

RELATED: Australia’s ‘NASA-like’ COVID-19 vaccine plan

WUHAN’S ‘RECIPE’ FOR DISASTER

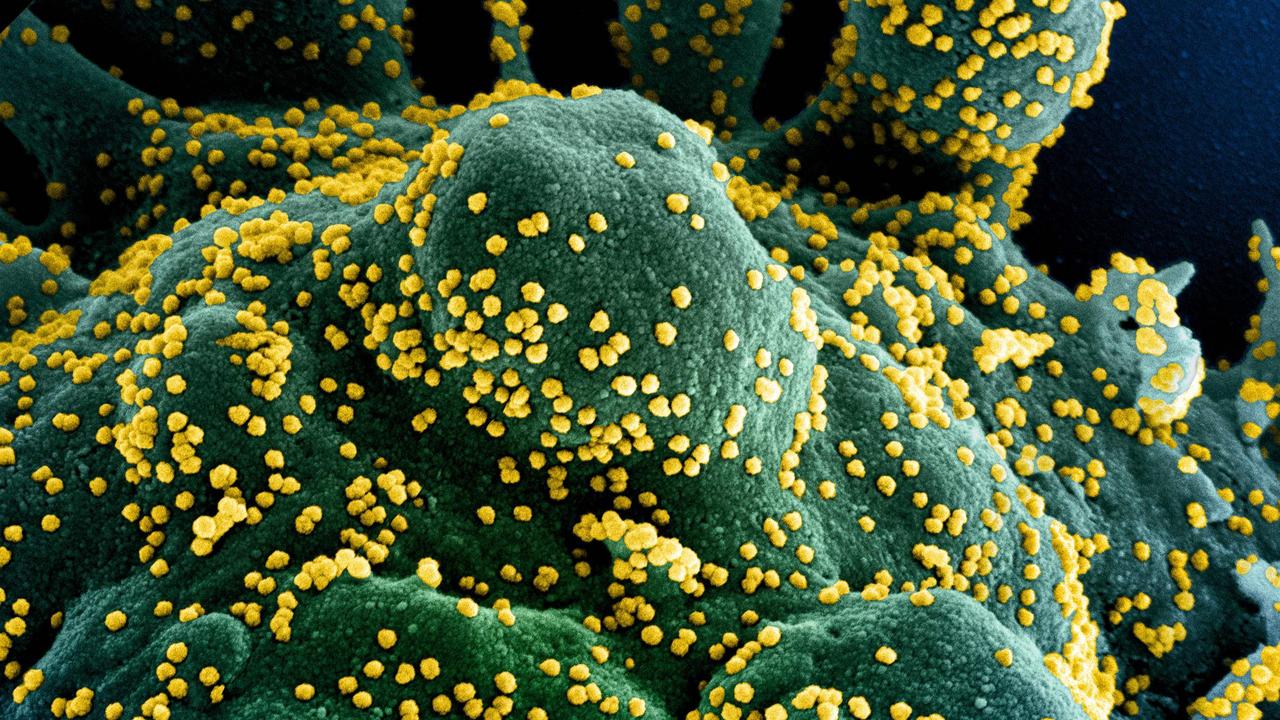

While WHO’s official findings from the mission were inconclusive as to the origin of coronavirus, Prof Dwyer said he believed it had started in China and most likely originated in bats.

And while virus cases really kicked off in a Wuhan “wet market”, he said it was probably being transmitted in the community for some weeks before that point.

“I must say the evidence for the virus being elsewhere before it took off in Wuhan is minimal … I think at this stage it’s a very big call to say it started elsewhere in the world and then came to China, however, that does need to be explored,” he said.

“There is no doubt the outbreak got going in China, in the market and then in Wuhan, but what happened a month or two before that is really key and open to debate.

“It’s more than likely it started there … the environment in Wuhan’s Huanan Market clearly was ripe for allowing the virus to break out.”

He said the fact there were 174 cases in Wuhan in December 2019 with only half having contact with the market, it seemed the virus had been circulating in the wider community as early as mid-November.

The investigation included specialists with backgrounds in animal viruses and epidemiology, and was focused on discovering how the outbreak started and what happened in the initial weeks.

The team visited a number of local markets, laboratories and hospitals and spoke with Chinese experts, medical officials and everyday patients, and while further investigations are needed, it is hoped their findings could help the world prevent or contain future pandemics.