UK records longest reduction in Covid-19 cases for six months

A country whose “let it rip” Covid-19 plan was slammed as “dangerous” and “unethical” could be on the cusp of having the last laugh.

It’s the nation that was derided for its risky “let it rip” attitude to Covid-19, removing almost every restriction on a single day and hoping for the best.

In the past few months, as cases sky rocketed, it seemed to be proof that was a flawed plan. There were fears a new “Delta plus” strain had taken hold and murmurs a Covid “plan B” should come into force, effectively a semi-lockdown.

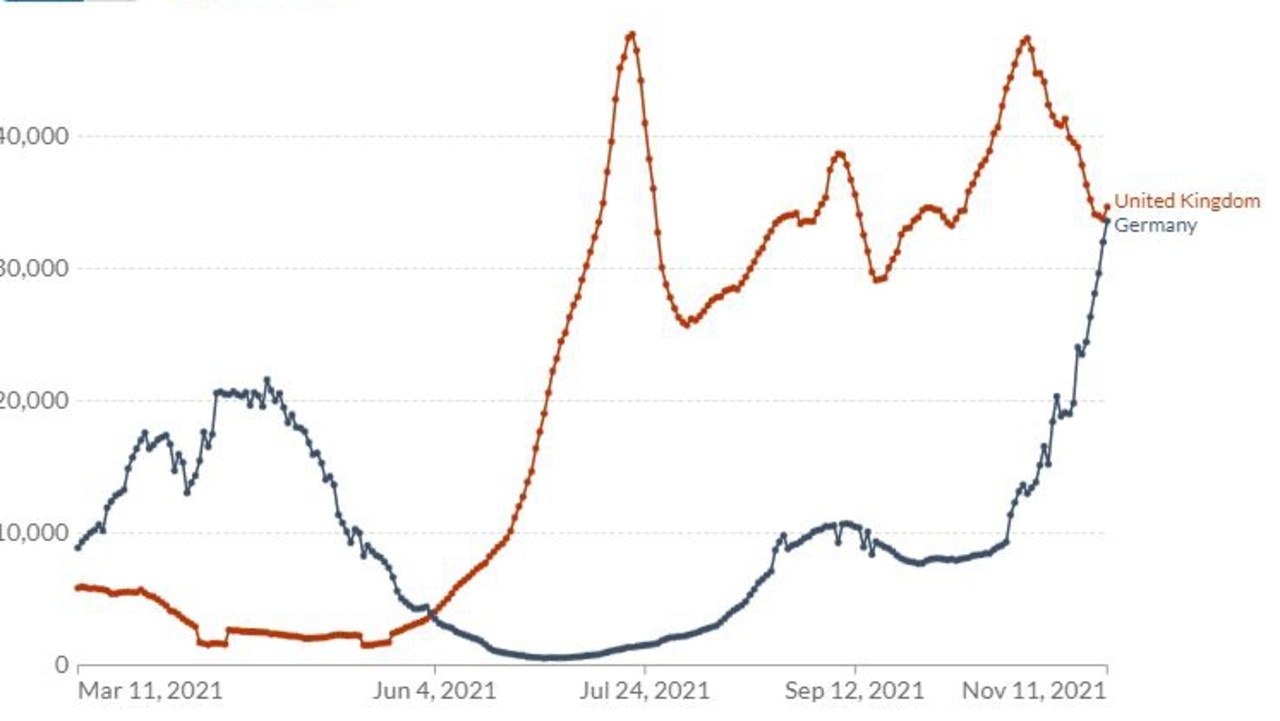

But the United Kingdom could be on the cusp of having the last laugh, with Covid cases dramatically falling for weeks just as new infections in other parts of Europe – where restrictions were tighter – head north.

A huge spike in cases in Germany means, for the first time in a long time, the UK is not the most Covid-prone nation in Europe.

An epidemiologist has said that the UK could have found a “unique” method of dealing with Covid based not around restrictions but immunity.

However other health watchers have cautioned that what might seem like a downward trend could just be a blip.

UK cases trending down while Europe goes up

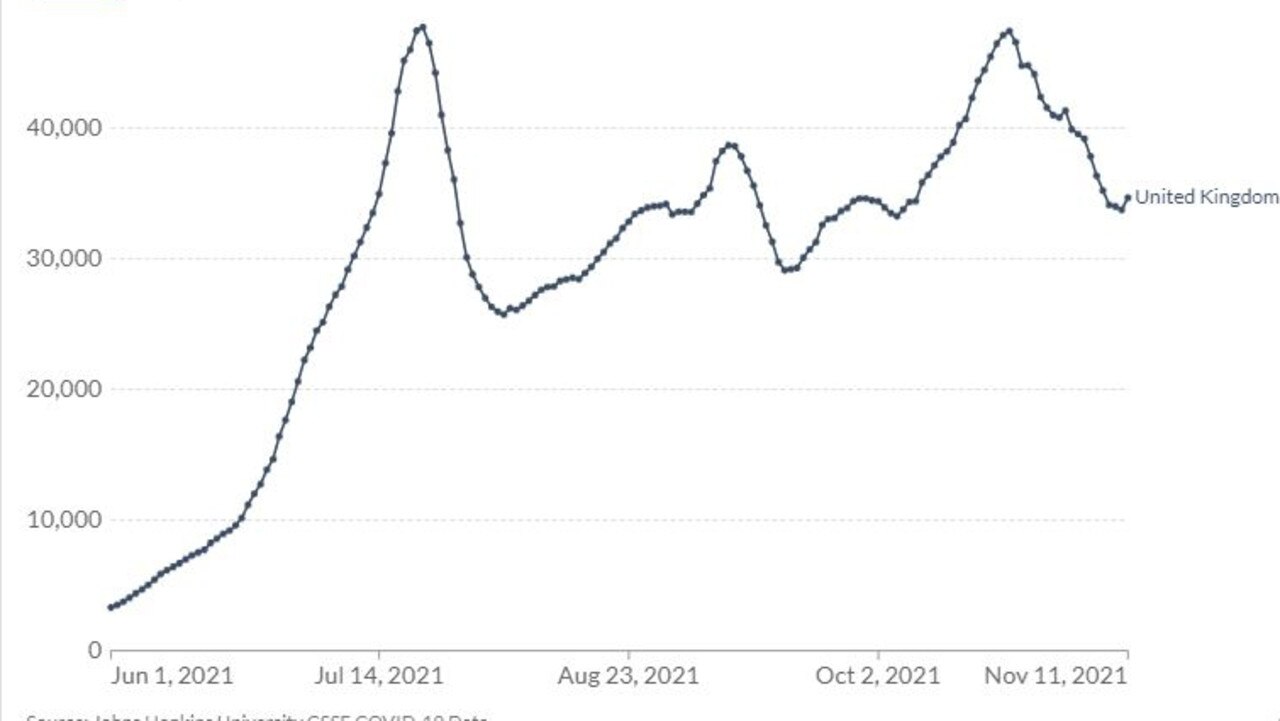

On Thursday, the UK recorded 42,408 new cases. It’s still a big number, and it was a rise on the previous day. But the seven day average of cases is now at 34,312 across the country, a 19 per cent decrease from two weeks previously. In contrast Germany recorded 50,196 cases on Thursday.

If you measure cases relative to population the UK is still surpassing Germany, but only by a whisker.

Britain’s unbroken decline in cases up until Thursday – 16 days – was the most prolonged in the country for six months.

It comes after cases spiked on October 22 at more than 51,000 a day. That was five times the daily cases at the time in Germany.

In late October there were concerns about the AY. 4.2 variant of Delta, nicknamed Delta plus.

Calls for “urgent research” into AY. 4.2 rang out amid fears it might be more transmissible and could have been the cause for a rise in UK infections.

However, health experts urged caution in singling out AY 4.2 as the cause, given Britain has had few if any restrictions ever since July’s so-called “freedom day”.

Britain’s ‘dangerous’ plan was slammed

The decision to ditch almost every Covid preventive measure in June was slammed as “foolish,” “dangerous,” and “unethical” by a number of health commentators.

But the UK government was committed to the “freedom day” plan which was memorably summed up by Prime Minister Boris Johnson as “if not now, when?”

The hope was that while Covid-19 cases might initially surge in the nation of 65 million, enough people would become immune, either through vaccination or infection, that by the time the risky winter period hit vast swathes of the population would be protected.

In late October, that hope seemed in vain with calls for the commencement of “plan B” restrictions which could include vaccine passports, working from home and mandatory face coverings to bring numbers down.

But since that late October peak, numbers have dropped without any plan B put into place.

Julian Hiscox, a professor of infection at the UK’s Liverpool University told newspaper the Financial Times that the case number fall was “unique” because it was due “almost entirely by the wall of immunity, rather than behavioural changes or restrictions”.

Reasons behind the UK’s case fall

Two reasons have been given for the fall – one focused on older Brits and one on younger people.

The UK is now partway through its booster program of administering a third shot. Around 80 per cent of people in England over 80 who are already fully vaccinated have now had a booster jab.

In the 70-79 cohort around 70 per cent are triple-jabbed. And it’s in these two age groups where cases have been falling fastest.

This means it could be a similar story to Israel which saw a spike in cases which was put down to waning immunity. In September, Israel was seeing as many as 11,000 cases a day. But following boosters, that’s now down to around 500.

It’s worth remembering that even during both the UK and Israel’s recent spikes in cases, hospitalisations and deaths were still far lower than during previous covid surges. The difference being vaccination.

“We could end up in a very nice window thanks to the timing of our booster program, whereby our peak in population immunity coincides with the winter months when the health service is under most pressure” said Prof Hiscox.

The fall in cases has last happened among younger Brits. That could be down to the rollout of jabs to 12-15 year olds who have been offered a single Pfizer dose since mid-October. However that program still has a way to run so it’s also possible that so much Covid has sloshed through schools that some kids now have a level of immunity.

UK may have reached peak covid for the year

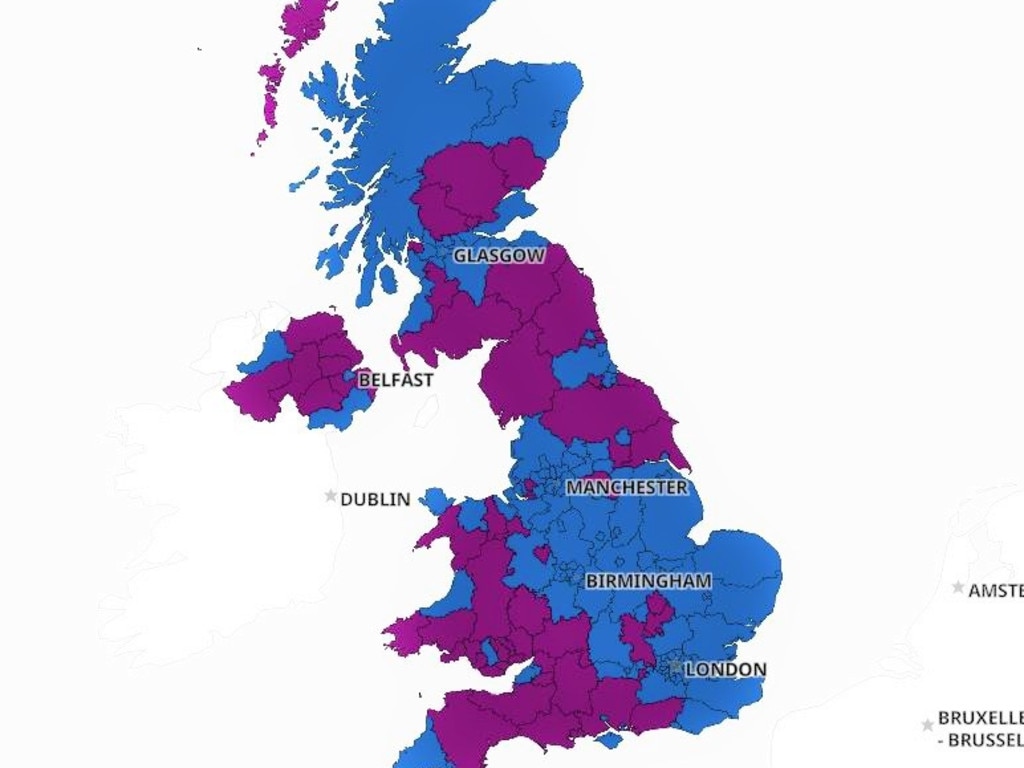

Further supporting that hypothesis is that cases in the UK are now generally lower in major cities like London which have had a high prevalence of covid.

A report by the UK Health Security Agency, which monitors covid cases, said it was in younger age groups where the turnaround was first noticed.

The government body as also said that hospital admissions for covid were down.

One study in early November, by health science company ZOE, predicted Covid cases in Britain might have peaked for the year. Again that was driven by a fall in cases in younger people.

“Young people have been driving the big numbers of cases, and the big numbers look from our data to have finished,” Professor Tim Spector of King’s College London told The Guardian earlier this month.

Falls still ‘rather small’

However, others said the decline in numbers didn’t mean Britain was out of the woods.

While booster shots and immunity conferred by infections might reduce some cases, that could be offset by more international travel and mixing indoors as winter takes hold.

Britain’s vaccination rate has also plateaued at around 68 per cent double jabbed of the entire population. That’s a decent level but it means there are still 20 million Britons who haven’t been immunised and are more at risk.

It’s slightly lower than Australia where the vaccination rollout began much later and it’s also far behind Portugal where 86 per cent have had two shots.

More Coverage

Assistant professor of epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Rohini Mathur told the Financial Times that the vaccination gap meant herd immunity in the UK might still prove elusive.

“The recent reductions we’ve seen are still rather small in magnitude and don’t yet indicate any sort of longer term trend,” said Prof Mathur.

Covid watchers will be focusing on Britain’s numbers to see if it has indeed found a way out of the pandemic or if it’s still looking for a pathway.