Appalling reason why one nation accounts for 20 per cent of global covid deaths

A country with just 4 per cent of the world’s population accounts for 20 per cent of Covid death rates. The reason behind it is disgusting.

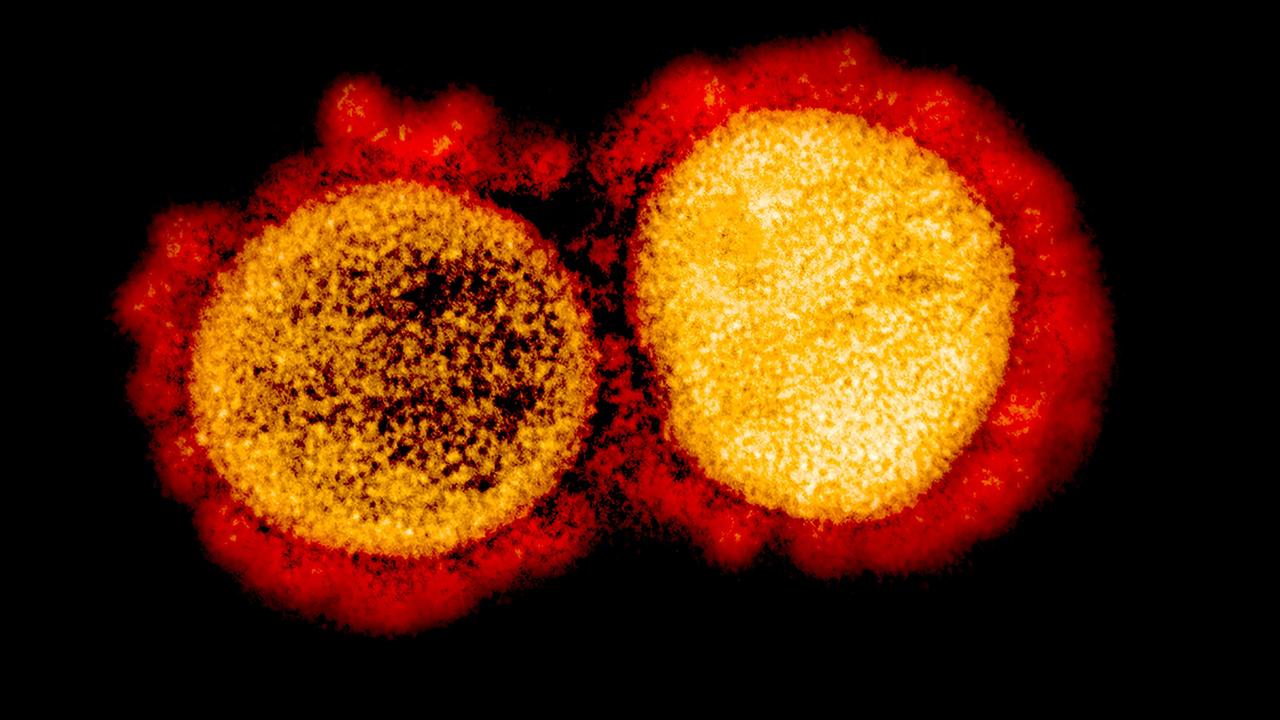

Covid-19 kills but lies are feeding it victims. An ongoing information war has caused one nation — with just four per cent of the world’s population — to suffer 20 per cent of global deaths.

That nation is the United States.

But the murderous infodemic has infected Australia.

UNSW associate professor of population health Dr Holly Seale says the evidence that pandemic misinformation kills is undeniable.

It may be accidental. It may be a simple misunderstanding.

“This is still the bulk of misinformation being sent around,” Dr Seale says. “Beyond that, we have those who are passing on rumours and myth, but they may not have an agenda beyond concern and well-meant intentions.”

Then there are those who deliberately lie.

“They have an agenda behind them,” Dr Seale says. “And, you know, this is nothing new. And it’s certainly not only associated with this Covid pandemic.”

Lies kill. Rumours wreck lives. Deliberate disinformation can destabilise whole communities. It’s been that way since the dawn of time.

“It’s right there in Genesis,” says UniSA social media researcher Dr Damien Spry. “Someone believed a lie. The rest of the books of the Bible just follow on from there.”

RELATED: Delta rips through most vaccinated country

What’s different now is the planet-sized megaphone of social media. And a sophisticated understanding of what triggers people’s emotions – and which people to trigger.

“We’ve tracked deaths linked to misinformation spreads on different platforms,” Dr Seale says. “It’s clear, misinformation kills.”

Pandemic infodemic

The United States is being wracked by a crisis of trust. Governors are refusing to save lives with social lockdowns. School boards are banning masks. Pastors are preaching that vaccines are a “mark of the beast”. Gym instructors are spruiking unproven remedies.

How does the average person deal with this? They turn to those they know and trust. Family. Friends. Social and community groups.

Dr Seale says these frontline influencers are being targeted by disinformation agents. She points to just one example uncovered by a study she was involved with.

Early on in the pandemic, an untrue rumour spread that drinking highly concentrated alcohol would kill the virus. The study found that there were 800 alcohol poisoning deaths related to this rumour.

“We only counted the ones we could be confident about,” she says. “The real death toll would have been much higher.”

The toll was high because the false claim quickly spread across the world via social media networks. It took time for the truth to catch up. And convince.

RELATED: Variant ‘600 times’ stronger than Delta

Dr Spry says ordinary people are doing the best they can with whatever information they have at hand. Often, that’s out of date, difficult to understand or irrelevant. At worst, it’s deliberately wrong.

Injected doubt

There’s misinformation. And then there’s disinformation.

“The very basic reason that misinformation exists is that people believe the wrong things with the right intentions,” Dr Spry says. “So they want to tell their friends and family because they believe that it’s right, and these people need to know.”

But misinformation provides fertile ground for disinformation.

“Disinformation is far more insidious because people are spreading falsehoods for the purpose of deception,” he adds. “It’s about political motives, commercial motives, profit motives …”

One usually follows the other in a destructive spiral.

The Covid-19 pandemic, Dr Seale says, was always going to have trouble with the truth.

“Immunisation has been seen as an easy, low-hanging fruit,” she says. “So the delivery has been poor. Of course you’re going to get annoyed if you can’t find the information you need. And of course you’re going to look for it somewhere else.”

But behind the health messaging is profoundly entrenched community polarisation.

One such example is the anti-vaccination movement.

“It’s got nothing to do with immunisation,” Dr Seale says. “It was chosen long ago as a way to try and undermine governments and gain political influence. They could have picked any topic. They just happened to choose vaccination”.

RELATED: ‘Worst combination’: UK’s new variant

The fallout of decades of such artificially induced doubt has primed the public to be – at the very least – afraid. Some have long since become well and truly militant.

“Those Sydney and Melbourne protests had a smattering of people carrying anti-vaccination signs,” Dr Seale says. “But they probably held those views before Covid. And they’ll hold those views after Covid.”

What matters is how much this spills over into the broader community.

And how receptive that community is.

“We’re paying the price of distrust,” Dr Spry says.

Professional deception

“I’ve been spending weeks now in training sessions with local community members and supporting culturally and linguistically diverse communities,” Dr Searle says.

“They’re not talking about what they’ve seen or read on the news. They’re not talking about pamphlets or government adverts. They’re talking about YouTube, WhatsApp, WeChat … They’re getting their information from often closed networks of friends, family and community. And this is where misinformation is being fed.”

It’s the closed social networks that are most problematic, she adds.

“We can track really well what’s going on in the public settings. But we don’t have a handle on what’s going on in the closed family and interest groups.”

But we can guess.

Dr Spry says the likes of Facebook and Google have built business models based on getting your attention. And they pay those who generate popular content – whatever it may be.

“What distinguishes them from mainstream media is that there is no editorial control. Nor are they held liable for their content. So there’s no need in their business model for truth and accuracy”.

Social media algorithms detect doubt, debate and dispute. They then inject whatever the most popular related content it has, regardless of its quality.

This keeps the discussion going – to maximise associated advertising profits.

The AIs don’t care if the truth is being manipulated by politicians or profiteers.

“As long as it’s demonstrated that deception can be either profitable or a means to achieve an end, then people will continue to seek to deceive,” says Dr Spry.

But, in times of crisis, politics becomes a problem.

People are primed to be cynical. But the situation can only be solved by truth and trust.

“There are two arguments here,” Dr Spry says. “One is about how to effectively run political campaigns. The other one is how to effectively govern. And until social media platforms are regulated in a way that means that politicians can’t take advantage of them, then they will need to take advantage of them to stay in power.”

Inoculating the truth

Like an immune system, people forewarned of a damaging tale can recognise it and defeat it.

Dr Seale says this burden usually falls upon key family and community members simply trying to do the best they can to help those they care about.

It can be a young football coach. A religious leader. An elder. The head of the local bingo club.

“They don’t have easily accessible, good information,” she says. “They don’t have the time to do the research. And they don’t know the character of everyone involved.”

Medical authorities must target these well-intentioned people in the same way the conspiracy theorists do. That means clear, straightforward communication. That means widespread distribution. That means good quality translations and audience targeting.

Mostly, it means trust.

“We need to develop resources to help these people on the ground,” Dr Seale says. “We must not only ask them to assess and think about what they’re being told, we must show them how.”

Dr Spry fears it may already be too late to vaccinate against the Covid-19 infodemic.

“When someone is convinced of an argument, they get invested in it, believe in it,” he says. “Then it’s harder to convince them that they’re wrong. So, essentially, changing someone’s mind is much more difficult than preparing them with the truth.”

But, short of authoritarian controls, it remains the only response our democracy has.

“What they all urgently need most is support,” Dr Seale says. “They need a toolkit. They need access to easily digestible sources in multiple languages. Only then can we inoculate communities from the misinformation that is clearly spreading out there.

“Even some well-translated pamphlets would be a good start!”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel