Britain’s Omicron crisis an ominous sign for Australia

In an ominous sign for Australia, one country is scrambling to prepare for disastrous consequences as its essential workforce is diminished.

Britain is bracing for an Omicron crisis. Its government is racing to minimise disruptions to essential services with expectations that up to a quarter of its workforce will soon be absent. Is this next for Australia?

Omicron is out of control. The new Covid-19 strain is ripping through Britain’s highly vaccinated communities.

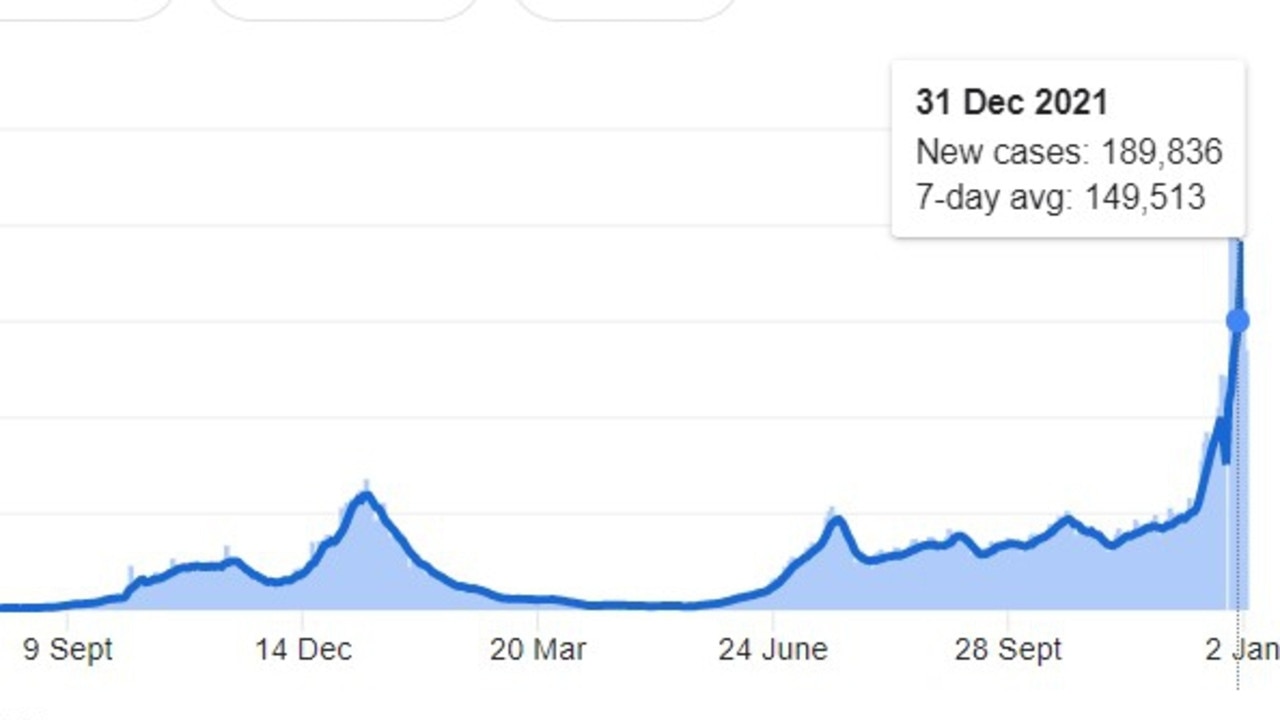

Like Australia, the now-familiar Covid infection growth charts there have switched from a curve into a near-vertical line.

It’s already caused massive disruption to the hospitality and aviation industries.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson is insisting the economy “remains open”.

While schoolchildren must once again wear masks, further restrictions have been ruled an “absolute last resort”.

That, it turns out, is coming at a price.

British cabinet ministers have been ordered to prepare for a worst-case scenario of one-in-four workers being ill or forced to isolate.

“As people return to work following the Christmas break, the high transmissibility levels of Omicron mean business and public services will face disruption in the coming weeks, particularly from higher than normal staff absence,” warns Chancellor Steve Barclay.

Professor Thas Nirmalathas of the University of Melbourne Centre for Disaster Management and Public Safety says the warning signs are already evident in Australia.

“This isn’t just about long queues for testing, crowded hospitals and hospitality industry closures,” he says.

“Those are just the early signs. We’re already seeing supply chain problems with some grocery shelves empty and long delays for the delivery of things like electronics.”

And Australia’s essential service providers - such as electricity, water and communications - need to have already activated their emergency contingency plans.

Omicron’s exponential disaster

The daily count of new cases across the United Kingdom amounted to 157,000. That’s a 50 per cent increase over a single week. Some 13,000 are now hospitalised.

Omicron’s extreme virility is raising fears that a large proportion of the nation’s workforce will soon be under mandatory isolation – resulting in disruption to essential services, the public service, childcare and transport.

And that’s before consideration is made on the extra burden for Britain’s National Health Service (NHS). Some 25,000 health workers were absent on Boxing Day – up from 19,000 a week earlier.

British rail transportation services have already been affected. Emergency timetables are being put in place amid soaring staff sickness levels.

The outbreak is already affecting British schools – even though they’re closed for the holidays.

Staff are testing positive. But they’re also informing principals they will have to stay at home to look after their own children as child care centres close.

Retired teachers are being asked to return to the classroom to ease shortages ahead of the new school year. But headmasters are warning that combined classes and school closures are “inevitable”.

Meanwhile, Britain’s Cabinet Office has ordered public service departmental heads to establish plans for absentee levels of up to 25 per cent. It has established a civil service “task force” to co-ordinate contingency planning and report risks of potential disruption.

Professor Nirmalathas says all levels of government need to work closely with Australia’s privatised essential services sector.

He says he is concerned about their ability to accommodate widespread illness among staff.

“It’s not that they’re unwilling to respond,” he says.

“it’s just that they can’t respond in a timely manner in most cases.”

Facilities are widespread. Service and specialist teams are small. And such groups need to be already operating isolated shift patterns to avoid superspreader cross-infection.

“That’s already just happening in most health systems, but it may have to happen in other essential services,” he says.

Covid escape routes

Prof Nirmalathas says most supply chain and essential services operators will have had two years to prepare plans for a severe outbreak. But Omicron’s incredible speed may leave them at the starting post.

“They’re already not operating at 100 per cent,” he says.

“These systems are already stressed. So whether or not their contingency planning can avoid risks to service delivery is somewhat uncertain.”

Reaction times to power, communications and water outages will almost inevitably become longer, he says.

“It’s almost like we have to anticipate these things will happen.”

And that means a much greater level of coordination between the state and federal governments and the private sector - as well as between competing private sector providers themselves.

“We might find ourselves really unprepared to deal with these consequences if we don’t.”

The British government hopes making free personal tests available to all who need them will reduce the number of those having to self isolate. It has also cut the isolation term for those confirmed as having Covid from 10 days to seven.

Experience out of South Africa, where the Omicron variant was first reported, shows a similar explosion in new cases. But data also indicates a similar rapid fall-off once the wave has peaked.

This has prompted hope within Britain that the current infection rate of up to 200,000 a day will soon rapidly drop away.

But it remains an unsubstantiated hope.

Australia must make the most of such experience before Omicron’s impact reaches a similar level here, says Prof Nirmalathas. Once the clinical data is in hand, Australia can begin adjusting its own isolation, work at home and capacity restrictions to suit.

But the threat to essential services must be seen as a wake-up call.

“As a country, we need a lot more contingency planning,” Prof Nirmalathas says.

“A basic level of coordination is needed in an ongoing capacity. We’re having fires, floods and pandemics like never before. We need federal and state governments to bring the public and private sectors together to ensure our essential services are secure.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel