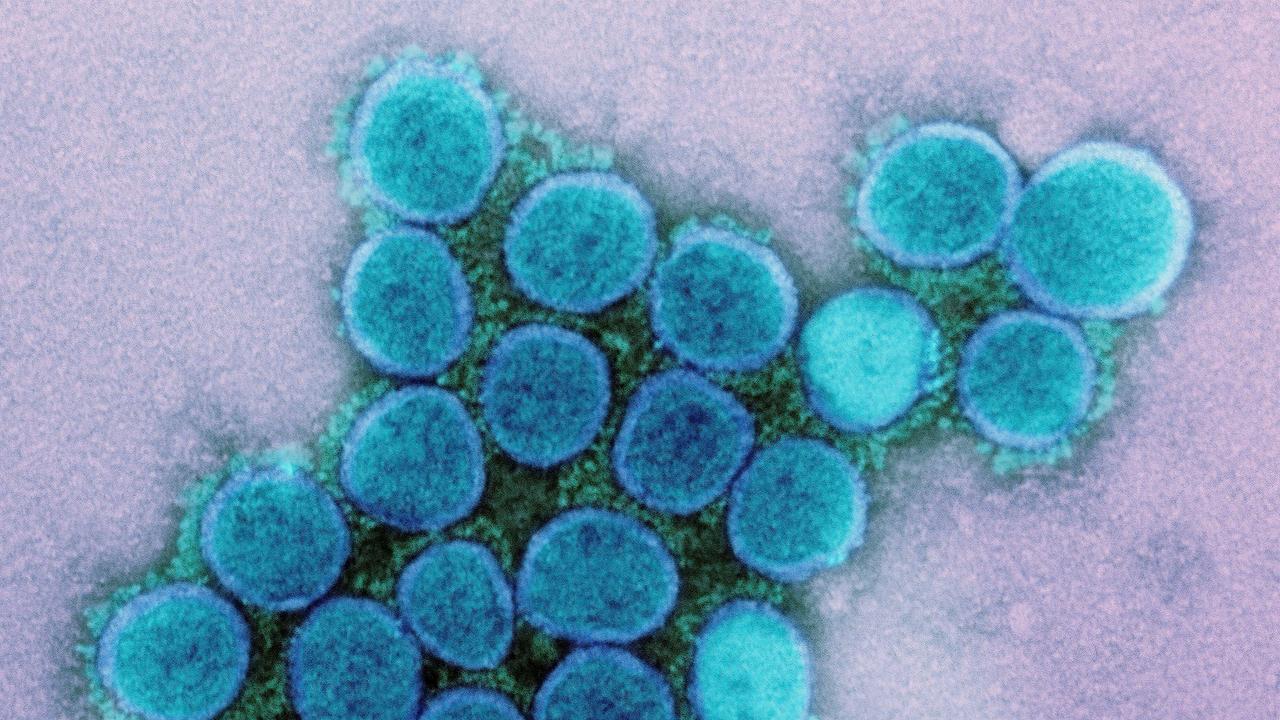

Coronavirus Australia: Why COVID-19 isn’t going anywhere soon

After a month of no deaths and cases declining, Australia is suddenly dealing with a devastating new virus spike – now we know why.

There’s a problem with success. It breeds complacency. As Australia bickers over pandemic restrictions, the deadly virus is exploding across the world. Have we forgotten we’re not out of this yet?

Worldwide, almost 10 million people are known to have contracted COVID-19. Nearly 500,000 have died. And the rate of infection only continues to accelerate.

Health services in the United States are so strained they’re proposing “lotteries” to distribute inadequate medical supplies equitably.

Brazil remains deeply in denial despite more than 50,000 deaths. And authoritarian Russia and China continue to obfuscate what their real figures are.

Amid it all Australia has stood out as a beacon of hope. Go early. Go hard. It was a policy that appeared to work well. But Victoria shows how fragile that success is.

COVID-19 appears entrenched in the community. It’s certainly no longer confined to cruise ship passengers. It’s not as easily traced as a returning tourist.

Instead, the virus is now feeding off entrenched weaknesses in our society.

RELATED: ‘Massive cover-up’: China’s lies exposed

RELATED: Search for clues to predict new virus outbreaks

WORLD WRITHING AROUND US

Borders are meaningless to a virus. It’s only Australia’s vast moat that is keeping the pandemic at bay. For now. The rest of the world, however, appears deep in the grip of the pandemic’s exponential destruction.

“The numbers of new infections are now growing at such a rate that while it took some three months to reach the first one million cases, the last million was reached in just eight days,” writes associate professor Adam Kamradt-Scott.

The International Security Studies expert at the University of Sydney highlights Indonesia as just one example. It is now recording 1000 new cases per day. And that’s despite meagre rates of testing. India’s daily infection rate has topped 14,000. And that figure is a significant under count. Even so, it’s now the fourth worst afflicted nation in the world behind Russia, Brazil and the United States.

Such is the scale of the pandemic that the WHO is warning of a worldwide shortage of oxygen concentrators needed to keep severe sufferers breathing.

More disturbingly, even those countries that showed initial signs of recovery are continuing to struggle with the virus. South Korea, which has been regarded for months as a poster child of an efficient COVID-19 response, has now entered a ‘second wave’.

And with the virus now deeply embedded in Victoria’s community, that may well be what the future holds in store for Australia.

COMPLACENCY: A FATAL BLUNDER

“It is easy to become complacent,” warns New Zealand’s University of Otago Public Health unit. “Many other countries pursuing a containment approach have had new outbreaks, notably Singapore, Korea and Australia.”

South Korea’s story sounds disturbingly similar to Australia’s. Its Centers for Disease Control blames the relaxation of restrictions to give businesses a boost. Nightclubs, bars, clubs and other venues were reopened. After a long, intense period of restraint – people relaxed. Social distancing guidelines were forgotten.

A UNSW study into Australia’s response reveals the majority of people had adapted their behaviour to become socially responsible, even when the risk seemed low.

“We found – somewhat surprisingly – really good compliance with both the hygiene-related behaviours and the avoidance related behaviours at that (March 18-24) time point,” says lead author Dr Holly Seale.

But the desire to adhere to rules and regulations wanes with time and relaxations. Maintaining a sense of caution needs governments to be clear about why people needed to follow behavioural recommendations, she says. It needs to move beyond a simple ‘do the right thing’ message.

“We think we need to prime people about what additional strategies may still need to be introduced,” Dr Seale says.

LIVES OR LIVELIHOODS?

Kamradt-Scott warns the world is becoming increasingly divided over the crisis. So too is Australia.

“Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, who has railed against ‘job-killing’ social distancing measures, appears unrepentant for firing his health minister even as he confronts escalating numbers of infections and an economic downturn in which Brazil’s economy is expected to shrink by 6.2 per cent,” he says.

Politics is also crippling the US: “More than two dozen public health officials across the US have been either fired, resigned or retired due to threats of physical violence, intimidation or persecution.”

Meanwhile, Australian state and federal leaders have been hurling political abuse at each over about the extent and pace of lifting restrictions.

Lockdowns remain controversial for their severe economic cost. But health experts say clusters among underemployed and low-paid workers at abattoirs, nursing homes and hotels shows how risky relaxing can be.

Sweden’s state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell remains unrepentant about his nation’s refusal to shutter schools, shops and restaurants in response to the pandemic.

“In the same way that all drugs have side effects, measures against a pandemic also have negative effects,” he said during a recent radio interview, highlighting the impact of unemployment, loneliness and domestic abuse.

But Sweden now has one of the world’s worst COVID-19 fatality rates (50.7 deaths per 100,000 infections).

LURKING IN THE WINGS

The major complicating factor of COVID-19 is its tendency to infect some people without generating symptoms. This reduces the effectiveness of tightly-targeted restrictions – such as particular communities, groups or workplaces.

“It is important to remind ourselves that active cases are not the ones we need to worry about,” the University of Otago researchers say. “By definition, they have all been identified and placed in isolation and are very unlikely to infect others. The real target of elimination is to stop the unseen cases silently spreading in the community.”

And that’s because how COVID-19 works remains mysterious.

“Two key issues in the epidemiology of COVID-19 that we still understand poorly is how common are asymptomatic infections and how much do these contribute to transmission?” says Professor Ivo Mueller of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

He points to a carefully studied outbreak aboard an Antarctic cruise ship. Of 128 passengers known to have contracted the virus, 81 per cent displayed no symptoms.

“In other words, there were four asymptomatic carriers for every ill passenger. If the same pattern is repeated elsewhere, this means that in countries that only test symptomatic cases, the true burden of infections may be five times higher than currently reported.”

This potentially makes limited containment measures much less useful as such carriers are virtually invisible.

Are these people more or less contagious than most? And what contributes to this?

“On the positive side, if people are asymptomatic they will not have a runny nose or cough so are unlikely to be a huge danger to society, but of course if people don’t think they have an infection they can be complacent with their own hygiene measures,” says Professor Brian Oliver of the University of Technology Sydney.

“As we ease the lockdown, it is important that we all remember to wash our hands and keep to appropriate social distances. It is also important that people don’t assume that they have been infected and now are immune from infection.”

WHERE DOES THIS END?

“Despite the dire global situation, there are a handful of places that have demonstrated it’s possible to suppress the virus’ transmission,” Kamradt-Scott writes.

New Zealand has a handful of new cases, all among returned travellers already in quarantine. It has no coronavirus restrictions beyond its closed borders.

Isolation is again proving an advantage for Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu. They managed to shutdown international travel before the pandemic arrived.

Australia is also an international success story. But will it remain that way?

“It remains important that good science supports the government’s risk assessment and management,” the University of Otago researchers say.

Then there’s the need for sustained high-levels of testing, aggressive contact tracing and community buy-in, and the addressing of community and workplace issues behind so many of the world’s COVID-19 hot spots.

Australia’s pandemic management, while mostly successful, is far from perfect argues Katrina Roper and Kamradt-Scott: “Australia’s pandemic preparedness efforts throughout the early 2000s established a solid foundation for the national COVID-19 response, but successive governments dropped the ball,” they write.

“Multiple recommendations to continue strengthening our preparedness efforts were ignored. Our national influenza vaccine manufacturing capacity that once guaranteed Australians priority access has been privatised.

“And our national medical stockpile of personal protective equipment appears to have been subjected to budget cuts and efficiency savings to the point where there was insufficient stock when the pandemic struck.”

In the end, it’s down to us. It’s down to washing hands. It is maintaining 1.5 metre gaps. It is wearing appropriate masks. It is self-isolating when sick.

“Importantly, though, all of these measures depend on leadership and a shared sense of vulnerability,” says Kamradt-Scott. “We need to marshal that, putting aside our differences and coming together to defeat a common foe. And we need to do it now.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel